#5 Study of Some Nigerian Art Music Compositions, Towards A Theory of Supplicative Musicology

UDC: 783.6(669.1)

COBISS.SR-ID 59630345 CIP - 7

_________________

Received: Jun 5, 2021

Reviewed: Jun 12, 2021

Accepted: Jul 20, 2021

#5 Study of Some Nigerian Art Music Compositions, Towards A Theory of Supplicative Musicology

Citation: Morohunfola, Kayode. 2022. "Study of Some Nigerian Art Music Compositions: Towards A Theory of Supplicative Musicology." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 7:5

Abstract

The strong need for supplication to higher authorities or deities has been a key part of people’s life since the creation of humans. In African religions and all the modern-day religions (Christianity, Islam etc.), supplication is a major part of their religious practices. Adherents of those religions are encouraged to take part in corporate prayers, they are further encouraged to have a quiet time with their maker. Praying in most of these religions is usually through speech, quietness and singing. The contextualization of some of those songs meant for corporate worship are supplicative. The focus of this research is on some art music compositions that are contextually supplicative. This work will do a musicological analysis of some Nigeria art music compositions that their contextualization is considered to be supplicative. The focus will be on three art music compositions with the following titles and composers: Emi yiogbeoju mi soke wonni (“I will lift up my eyes unto the hills”) by T. K. E. Philips, Adura fun alaafia (“Prayer for peace”) by Ayo Bankole and Jesu wafara re han (“Jesus come and manifest yourself”) by Debo Akinwumi. The study will be rested on ‘Supplicative Musicological Theory’ coined by this author. In other to achieve the goals of this qualitative research, the author will depend on direct interviews and interviews through internet sources such as electronic mail, WhatsApp and the Facebook. The author will also use the scores of the songs in doing the musicological and textual analysis. The author’s secondary sources are textbooks, and other bibliographical materials such as journals, magazines and other internet sources. Many research works have explained the effectiveness of music as a strong means of communication. This research is recommending further contextualization of art music to address the corporate and individual supplicative needs of the society.

Supplication, Contextualization, African Art Music, Vocal Music, Syncretic Music, African Contemporary Composers, Syncretic Music

Introduction

The New Harvard Dictionary of Music, described Composition as ‘the activity of creating a musical work’ (Randel 1986, 182). It was further described as an activity that took place prior to performance, which is in opposition to improvisation. Onwuekwe (2016) also defines composition as ‘the art of creating original music for one or more media; it is the art of combination of well-organized sounds that are pleasing to the ear. It involves a combination of sounds to create beautiful melodies and harmonies.’ In another article, composition was defined as the ‘art of writing down original music for sacred or secular purposes for voices and or musical instruments’ (Onwuekwe2017, 218). In her own description on a typical composer of African music, Agu (2018, 147), described a contemporary composer of African music as an individual with a bi-exposure to African indigenous knowledge of music systems and western music. While a composer is a musician who is an author of music in any form, including vocal music, instrumental music, electronic music and music which combines multiple forms.

Music could be composed for instrumental mediums, vocal music and instrumental/vocal music. One of the key pre-compositional considerations by composers of musical works that are lyrical is, what will be the contextual focus of the song. A number of researchers have written articles on contextualization of songs and the extra-musical purposes of music. In all the musical styles that are textual, styles such as the traditional music, hymnody, art music and the popular music, consideration for the textual focus is imperative.

In his book, Popular music in Western Nigeria, Omojola (2006), did a copious description of some extra aesthetic roles of music, which is centered on the verbal conception of music in the Nigerian society. According to him ‘Music as a product of the human mind cannot but reflect other aspects of the human thought processes’ (2006, 13). He further highlighted, how it can be used to lull a baby to sleep, how it can be used to express malice within neighbors and how it can be used as narrative during story telling sessions, as some of the extra musical usage of music. A number of authors also commented on the usage of music as a medium of expression in every aspect of group and cooperate worship in African indigenous worship (Nzewi 1984; Ofosu 1997:34; Oludare 2017, 51), also corroborate the above view while stating how African music functions traverse social, cultural and didactic functions. He listed some other extra musical roles as social interaction, economic empowerment, political commentary, tool of education advancement, cultural indicator and historical documentation.

According to Martin Leckebusch, the executive vice president of the Hymn Society of Great Britain and Ireland, ‘words that seem cold on the page can come to life when set to music: the use of an appropriate tune takes the words to another level’ (In August 17, 2020 interview “What is the Point of Singing Hymns” , conducted by Lanre Delano, Chopin Church Organ Projects in Nigeria, via the YouTube). He further said, the experience can lead to a deeper emotional level that will not be possible if the words are read. This is in tandem with a 19th century statement cited by Vidal (n.d., 1), about the 1868 visit of Adolphus Williamson Howells, who was the first Commissioner of education in West Africa. While Howells was advocating for increased emphasis on music in the new Church, he stated that “Sacred and solemn music had resulted in conversion where preaching has failed”.

Vocal music has shown a creative dialectical relationship between the music and the society. Music has been contextualized to meet some of the societal needs since time immemorial. In his paper titled, ‘Transformative Musicology: Recontextualizing Art music composition for societal transformation in Nigeria’, Adedeji (2010) advocated for contextualization that will address the contemporary social challenges of the society. The contextualization of some of this music are transformative, instructional, testimonial, political communication and in praise of a supreme being. In the area of liturgical compositions, traditional religious music, secular music and traditional music, there are examples of songs contextualized for supplicative purposes. There are also a good number of composers of African hymnody, gospel music, popular music, art music and the liturgical art music who have contextualized their compositions to meet some supplicative needs of the society. This research will be particularly focused on three supplicative liturgical art music compositions of, T. K. E. Philips (Emi yiogbeoju mi so kewonni), Ayo Bankole (Adura fun alaafia) and Debo Akinwumi (Jesu wafara re han).

Supplicative Music Theory

The word supplication, also known as petitioning has been described as a form of prayer wherein one party humbly or earnestly asks another party to provide something, either for the party who is doing the supplicating or on behalf of someone else (source). The word supplication has been described as a sort of prayer, a request for help from a deity, in addition to the popular view from a religious perspective where they often call it prayer, it can also be applied into any situation where there is a need to entreat someone in power for help or favour (source). From the definitions above, we could see that supplications could be directed to God, or some other higher spiritual authorities. Supplication could also be directed to humans, to obtain one favour or the other. In all of the above supplicative contexts, music has served as one of the major means of communicating those supplications.

Supplication is one of the key values of the African traditional religion. A good number of scholars have commented on issues relating to supplication in their research works. In his work, ‘Traditional Religious Belief System’, Segun Ogungbemi (2017, 310) explained the structure of Yoruba belief system, and described Olodumareas the superstructure on which the Yoruba belief rest. Next on the hierarchy are the principal deities, such as the Orisa-nla, Orunmila, Ogun, Esuand Yemoja. The next on the organogram are the deified individuals such as Sango, Orisa-Okoand Moremi. The view above was corroborated by Falola (2001, 34-35):

The Yoruba have constructed a hierarchy of spiritual forces, similar to their political hierarchy. (...) In this hierarchy, God is the supreme deity with the ultimate power, the creator of the universe, the final judge

Furthermore, in the Yoruba belief system, Olodumare, provided avenues for humans to solve their diverse problems through the principal deities and the deified individuals. Individuals are also free to serve the gods or goddesses that they belief will be of benefit to them (Ogungbemi 2017, 310-311). In a bid to be in constant communion with the superior spiritual power, the need for worship and veneration became an important part of these religions. According to Idowu (1962, 107):

worship is an imperative urge in man……Man perceived that there was a power greater than himself, a power which dominated and controlled the unseen world in which he felt himself enveloped; a power which he therefore made out by intuition to be the ‘ultimate determiner of destiny’.

Johnson-Bashua (2017, 65), corroborate the imperativeness of supplication in her paper titled ‘Libation, Homage and the Power of Words’, according to her:

words spoken through prayer, incantations, and invocations are the ‘tender bridge’ that links us with a vast, living spiritual world which has the potential to reinvigorate a disconnected spirituality.

She further did an expository explanation of three important processes in Yoruba traditional religion that are also supplicative: the libation, homage and the power of words.

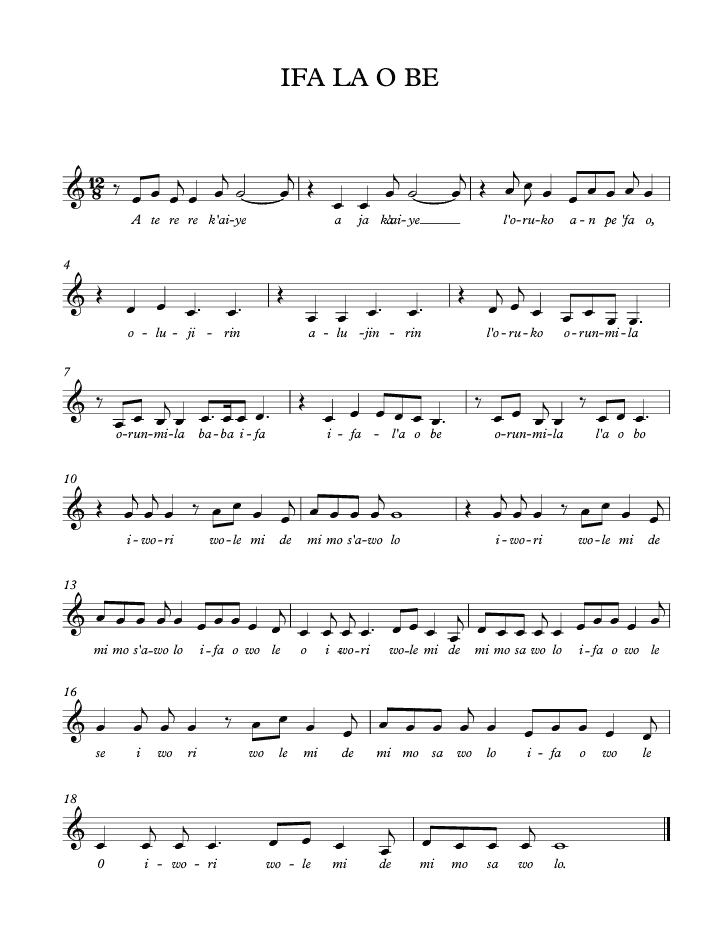

In the worship and prayer to the supreme deity (Olodumare), to the divinities (Orisa-nla, Orunmila, Ogun, etc.), and the deified individuals (Sango, Orisa-oko, Moremi etc), music has been a major means of expression. The song in the Example 1, is a typical supplicative song by an Ifa Priest. In the song he extols some of the virtues and attributes of Ifa and Orunmila. He concluded the song by pleading with Ifa to protect his family.

Ifa La O Be

Lyrics

Aterere k’Aiye, Aja k’Aiye

L’oruko an pe Ifa o

Olujinrin Ajajinrin l’oruko Orunmila

Orunmila Baba Ifa, Ifa la o be

Orunmila la o bo

Iwori wole mi de mi, mo s’awo lo

Ifa o w’ole o

[The one who is ubiquitous and also pandemic,

That’s the name we call Ifa

Olujinrin and Ajajinrin are the names of

Orunmila

Orunmila the father of Ifa, we will beg Ifa

We will worship Orunmila

Watch my house for me Iwori, am going for Ifa

Consultation

Ifa will watch my house]

In his paper, ‘The Vociferation of the oppressed: Emphatic underpinnings of Contemporary indigenous Christian prayer songs in Nigeria’, Adedeji (2017, 108), described some extra musical roles of music. According to him

music is created not just on aesthetic or artistic levels but also on emphatic levels. (...) music is used as a tool for socio-economic struggles and psycho-spiritual emancipation of the oppressed.

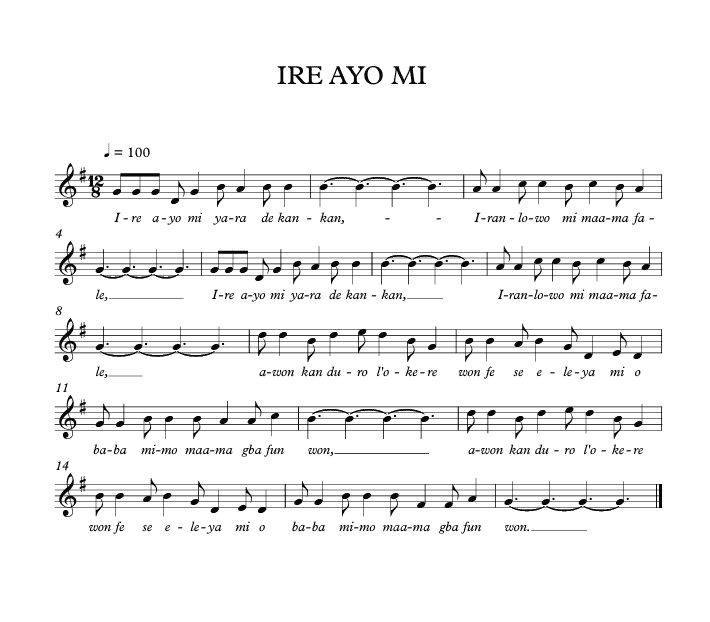

Furthermore, he described the prayer pattern in most Nigerian Churches these days as ‘radical’. He further explained how the prayer has been expressed musically. He listed invocation, warfare, supplication/petition, protest and deliverance as the divisions of prayer songs. Part of his research findings showed that adherents of the prayer fellowships are relieved psychologically after communicating with their God through the singing of those lyric airs contextualized as prayer (2017, 112). The song in the Example 2, titled Ire ayo mi (‘My goodness and joy’) is a typical song of supplication in Christian gatherings. The song is a plea to God for goodness and joy, the song went further, telling God to speedily harken to the request of the singer, to prevent evil people from mocking him/her.

Ire Ayo Mi

Lyrics

Ire ayo mi yara de kankan

Iranlowo mi ma ma fale

Awon kan duro lokere won fese

Eleya mi o

Baba mimo ma ma gba fun won

[Hasten to me, goodness and joy

My help should not be delayed

Some people are staying afar, waiting

To mock m God will not allow it to be possible]

The earlier definition of supplication also explained it in a non-spiritual way, the definition explained how one party can pray or plead earnestly with another party for one favour or the other. One vivid example is, when members of a community or a group within the society or individuals are pleading for a favour from the government. In one of his tracks, Ebe la be ‘joba(‘We plead with the government’) in the Example 3, Kolington Ayinla’s pleaded with the government to reduce the cost of living that was considered to be very high during the administration of Ibrahim Babangida in Nigeria (1885-1993).

Ebe La Be 'Joba

Lyrics

Ebe la be ‘joba

Ki won gbawa

Gbogboonje tan je

Gbogbo e lo lewo

Ebe la be ‘joba

ki won gbawa

[We are making a plea to the government

That they should deliver us

All the food we eat

Are becoming expensive

We make a plea to the government

That they should deliver us]

Another example are the politicians canvassing for votes from the populace. The music below (Example 4) is a political song used during the campaign of Christopher Alao Akala, a former governor of Oyo State (2006-2006) (2007-2011). The song was one of the songs he used in canvassing for votes from the people of Oyo state. In all of these examples, music has been used as a means of expressing supplication.

Alao lo le se

Lyrics

Alao lo le se,

Akala lo le se momo

Alao lo le se, o tin se,

Eje o se, Alao lo le se

O da mi loju

[Alao can do it

Akala can do it I know

Alao can do it, he has been doing it

Let him do it, Alao can do

I am sure of it]

Analysis Of Some Supplicative Liturgical Art Music Compositions

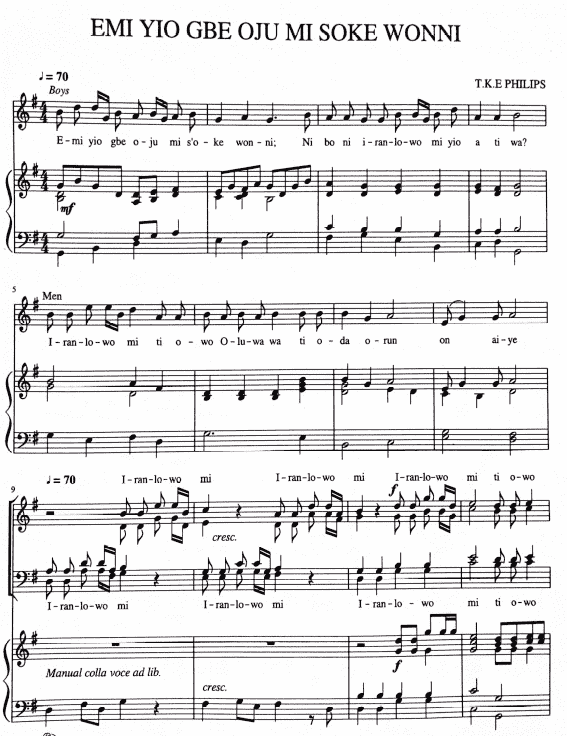

Emi Yio Gbe Oju Mi Soke Wonni

Author: T. K. E. Philips (1884-1969)

Thomas Kings Ekundayo Philips, a Nigerian Organist, Choirmaster, Composer and Musicologist, was born into the musical family of Bishop Ekundayo and Marian Philips on the 8th of March, 1884. His father was one of the earliest Organist in Lagos. He started his musical journey in Ondo under the tutelage of his father. He later moved to Lagos to further is education. While he was in Lagos, his guardian’s name was Archdeacon N. Johnson, the Vicar of St John’s Anglican Church, Aroloya, Lagos who is also an Organist. He continued his musical development under the instruction of Archdeacon Johnson. He later served as the assistant Organist at Aroloya as a teenager. When Philips was 18 years old, he was appointed the Organist at St. Paul’s Anglican Church Breadfruit, Lagos. Philips served as the Organist of the church from 1902 till 1911.

Philips attended the Church Missionary Society (CMS) Grammar School in Lagos, before travelling abroad to study music at the Trinity College of Music, London. While at the Trinity College, his major instruments are Organ and Violin. He graduated with an Associate diploma (ATCL), in 1914, after which he returned to Nigeria. Philips traveled back to London to study for a Licentiate diploma in composition (LTCL), in 1934. His excellent performance during the licentiate exams made the school to award him a Fellowship of the Trinity College of Music (FTCL honoris causa).

Philips is the second Nigerian to study music formally in Nigeria. Upon his return to Nigeria, he was appointed the Organist / Choirmaster at the Christ Cathedral Marina Lagos, a position he held until 1962, a period of 48 years. As a composer, Philips was a key figure in the emergence of syncretic music in Nigeria.

TEXTUAL ANALYSYS

Lyrics

Emi yio gbe oju mi soke wonni

Ni boni iranlowo mi yio a tiwa

Iranlowo mi ti owo Oluwa wa

Ti o da orun ohun aiye

Iranlowo mi ti owo Oluwa wa

Tio da orun ohun aiye

Ohun ki yio je ki ese re ki o ye

Eni tin pa o mo ki i to gbe

Kiyesi eni tin pa Isreali mo

Ki i to gbe, beni ki i sun

Oluwa olupamo re

Oluwa lojiji re, lowootun re

Orun ki yio pa o nigbaosan

Tabi osupanigbaoru

Oluwa yio pa o mo,

Kuro ninu ibi gbogbo

Yio pa okan remo

Oluwa yio pa alo ati abo re mo

Lati igbayi lo

Ati titi lai. Amin.

[I will lift up my eyes to the hill

From whence comes my help

My help comes from the Lord

Who made heaven and earth

My help comes from the Lord

Who made heaven and earth

He will not allow your foot to be moved

He who keep you will not slumber

Behold, He who keeps Israel

Shall neither slumber nor sleep

Nor the moon by night

The Lord is your keeper

The Lord is your shade at your right hand

The Lord shall not smite thee by day

The Lord shall preserve you

From all evil

He shall preserve your soul

The Lord shall preserve your going out and your

Coming in

From this time forth

Forever more. Amen.]

In the composition, the composer used the Yoruba translation of Psalm 121, a biblical passage. This passage is one of the renowned passages used by Christian faithful during prayers. The passage is an expression of devotion and loyalty to a monotheist God as believed by Christians. The Chapter is considered as a prayer of divine help and protection. The passage is further regarded as one of the most powerful psalms for divine help and protection. At crossroad situations in life, the passage is a popular passage used by Christians to pray to their God. It is further believed that the usage of passages such as Psalm 121 will place adherents of the religion on a pedestal that will be beyond the reach of any satanic power. Expressing the passage through singing will give believers the same psychological satisfaction as expressing it verbally.

STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS

The music is arranged for male choir comprising of boys and men with keyboard accompaniment. The song has been adapted for mixed choirs (male and female) in many cases. The pattern of the composition is through composed. The music began with an interchange of semi choirs (boys and men) singing in unison between bars 1 to 8. There was antiphonal singing between the men and the boys from bar 9, before the texture changed to homophonic texture from bars 12 to 15. A flattened seventh was sounded by the bass on bar 15, a note that changed the tonal center from G to C in the subsequent baritone solo from bars 16 to 23. The choir in unison continued from bar 23, before changing to homophonic harmonic style from the last beat on bar 25 to bar 28. The harmonic style became contrapuntal from bars 29 to 33. The choir sang in unison from bars 34 to 38. From bars 39 to 46, the four parts sang a parallel melody on different modes beginning from the altos to basses to tenors and the trebles with a one phrase alto counter melody towards the cadential section of the basses (bars 41 and 42), and a similar counter melody by the tenors before the cadential section of the trebles (bars 45 and 46). The harmonic pattern from bars 47 to 60 is a combination of unison (47-50, 56-58), counterpoint (52-54) and homophonic pattern (50-52, 54-56 & 69-60).

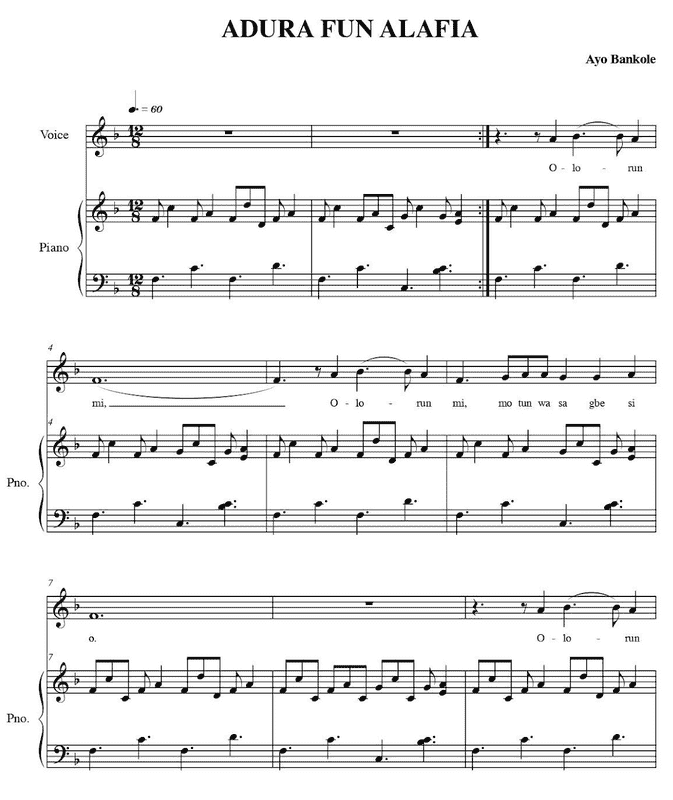

Adura Fun Alafia

Author: Ayo Bankole (1935-1976)

Ayo Bankole, Musicologist, Composer, Organist and Choirmaster, was born into the musical family of Theophilus Abiodun Bankole in 1935, his father being an Organist, served in a number of Nigerian Churches, including the Hoares Memorial Methodist Cathedral, Yaba, Lagos. While his mother was a music teacher at Queens College Ede, and the Organist at First Baptist Church Ede, Osun State. Bankole has his first exposure to music through his parents.

He attended the Baptist Academy Lagos, while at the school, he was the school Organist. He later proceeded to the Guildhall School of Music and Drama to study Composition, Piano, and Organ. While he was in the United Kingdom, he earned the prestigious fellowship diploma of the Royal College of Organist (FRCO). Bankole later studied for his Bachelors and Master’s degree at University of Cambridge, and University of California (UCLA) where he studied ethnomusicology.

After his education, he worked briefly with the Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN), and later with the University of Lagos as a lecturer, a position he held until his death in 1976.

TEXTUAL ANALYSYS

Lyrics

Olorun mi, mo tun wasa’gbesi o

Mo wagb’adura, si o o

Mo wa tuba mokun le

Mo wole fun O Baba

Mo wa ranti gbogboawon to walojuogun

Mo gba dura mogbadura fun won Baba

Tojugbogbo won patapata

Tojugbogbo won porogodo

Aseyinwaaseinbo

Waf’itura fungbogbowa

Wa fi ayo fun gbogbowa

Wa fi oye fun gbogbowa

Mo be o o,

Waf’itura fun gbogbowa

Mo tun wasagbesi o

Olorun mi mo tun wasagbesi o

Mo wa ranti gbogboawon to walojuogun

Mo gbaduramogbaduara fun won o

[Take care for them allMy God, I’ve

come to plead with you

I’ve come to pray to you

I’ve come to plead for forgiveness on my knee

I bow down for you Father

I remember those at the war front

I pray for them Father

Take care for them all

Take care for them all

The long and short of the matter

Give all of us relief

Give all of us joy

Give all of us understanding

I plead with you

Give all of us relief

I have come to plead with you

My God I have come to plead with you

I remember all who are in war front

I pray for them all]

The song is a prayer for peace. The text opened with a statement of purpose, which is a plea for a number of issues bothering on peace. He started it with a prayer of forgiveness. Forgiveness is one of the key instructions given by Jesus to His followers, this was recorded in Mathew 6: 12 and Luke 11: 4. Christ followers must pray for forgiveness, furthermore, they must forgive those who sinned against them. The two-sided dimension of this stated scriptural instruction is compulsory to obtain God’s mercy. The song continued with an expression of a deep obeisance to the maker. In most cultures in African, bowing down or kneeling down is a sign of respect, and also a posture for people appreciating or pleading for a favour from higher authorities. Bowing down or kneeling down is also a culture of Christ believers during prayers. Scriptural passages such as Luke 22 :41, Psalm 95: 6 and Acts 20: 36 are some of the examples of kneeling down and bowing down in the Bible. He then prays for those on the war front, he prayed for relief for everyone, he prayed for joy and understanding. When we look at all the prayer points he raised in the song, we will notice they are important points that will subsequently lead to peace.

STRUCTURAL ANALYSYS

The melody of the song is within a narrow range of a major seventh (C4- B flat 4). The range showed that the melody will be convenient for most vocal range. The composer was able to bring colour to the melody by a good variation of a number of rhythmic modes. One of the very good quality of the melody is the perfect adherence of the melody to the tonal inflection of the textual meaning of the song. The accompaniment showed a strong element of African pianism and drumistic piano. The ostinato pattern with a little variant was used in the accompaniment of the song in a style that simulate the Yoruba dundun cyclic drumming.

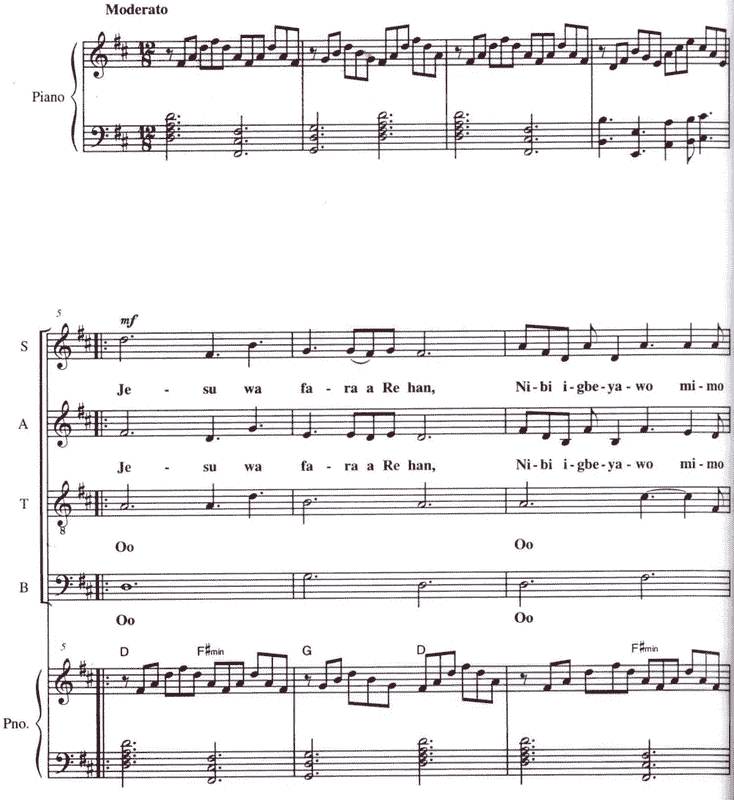

Jesu Wa Fara Re Han

Author: Debo Akinwumi (1956-2005)

Emmanuel Adebowale Akinwunmi, a Choirmaster, Composer, Guitarist and Music Lecturer, was born in 1956, into the family of Elijah AjiboyeAkinwumi and Grace MonilolaAkinwumi of Ogbomosho. He completed his elementary school at Okelerin Baptist Day School in 1968. He later attended the Ogbomosho Grammar School between 1969 and 1974 for his ordinary level school certificate. Akinwunmi completed his Higher National Diploma (HND) in Music at the Ibadan Polytechnic in 1983.

He began his journey into music when he joined his high school choir under the directorship of one of his teachers, Mr. E. A. Oke. He furthered his interest in music by joining a number of musical groups including his Church choir at Ori-Oke Baptist Church Ogbomosho. His quest to be a part of standardizing Yoruba Art Music because of its tonemic peculiarity coupled with arranging of standard four-part polyphonic music for choir in the Yoruba language was a major motivation for his enrolment for formal musical training at the Ibadan Polytechnics.

After the completion of his education, Akinwumi taught in a number of post primary schools, which includes the Baptist College Iwo. He later became a lecturer at Kwara State College of Education Ilorin from where he transferred his services to Emmanuel Alayande College of Education Oyo. He was an Assistant Chief Instructor in the college at the time of his demise.

TEXTUAL ANALYSYS

Lyrics

Jesu wa fara re han

Nibi igbeyawo, mimo yi,

Fi Ibukun re

Fun Oko ati Aya

Jeki won le wa ni irepo

Ni ojo aiye won

K’aiye ma le ya won

K’esu ma le ya won

Ire at’ayo, ko ma ba yin gbe

Ko ma ba yin gbe lo lai

El’enu meji oda

Baba ma se won, lelenu meji

Se won l’olotito

Se won l’onigbagbo rere

Ki won le beru re

Fi anu re, sori Oko a t’aya

[Jesus come and manifest yourself,

In this holy matrimony,

Give your blessing,

For the Groom and the Bridegroom,

Let them be united,

In their lifetime,

The world will not separate them,

The devil will not separate them,

Goodness and mercy will dwell with you,

Goodness and mercy forever,

Double tongue is not good

Don’t let them be double tongued,

Let them be truthful,

Let them be good believers,

Let them fear you,

Let your mercy be on the husband and the wife]

The song is composed as an anthem for a wedding ceremony. The text of the song is a supplication to God on behalf of the newly married. It started with a prayer for God to manifest himself in the wedding. The song prayed that the couple will not be double tongued in their dealings with people, a term that is synonymous with being deceitful or dishonorable. The song prayed against divorce for the newly married. Furthermore, the spiritual life of the couple was not left out, he prayed they will be good followers of Christ. The song also prayed for God’s mercy and favour for the newly married.

STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS

The music is arranged for Choir and piano. The harmonic style is largely homophonic with a strong element of counterpoint and polyphonic harmony. The inflexional correspondence between the melody and the Yoruba meaning of the word is perfect in the melody of the song. In other to follow the correct tonal harmony of the melody, adherence of the harmony to the correct tonality was not totally possible.

Conclusion

The definitions of musical composition by a number of scholars, was examined in this research effort. The bi-musical exposure of a typical African contemporary art music composers was also explained by a number of authors. The work went further to explain the importance of thematic focus as a pre-compositional consideration in vocal music. This verbal conception was further described by Omojola (2006), as an extra aesthetic role of music, which is a product of human mind. It is important for composers to determine what the lyrical context of the composition will address. Vocal music has been used for, or to achieve a number of extra musical purposes such as public pedagogy, transformational purposes, historical records, expressing love, to promote government policies, advertisement and religious purposes. The work showed how some composers have used music to meet some supplicative desires of the people singing or listening to the song.

Supplication is synonymous to petition and prayer. Supplication can be described as entreating for favour from someone in position to help the petitioner. The research discussed the issue of supplication and the role of vocal music from the angle of Yoruba traditional religion, it went ahead to discuss it from the perspective of Christian religion. Furthermore, how popular music has been used to plead with the government of Nigeria for a better condition of living was also discussed. Another supplication which is common in the pre-election preparation is when politicians use vocal music amongst other things to canvass for votes was also discussed. In all of the aforementioned supplicative instances, the work gave practical examples.

In the development of African art compositional musicology in the last century, composers of vocal art music have been motivated to address a number of extra musical issues in their vocal compositions One of which is asking God for one favour or the other. The research is focused on three of such Art music compositions, composed for liturgical usage. In one of the earliest Yoruba art music choral compositions titled Emi yiogbeoju mi soke wonni (‘I will lift my eyes unto the hills’), T. K. E. Philips used the Yoruba translation of Psalm 121, which is one of the psalms that are renowned for praying by Christian faithful and even some non-Christians. Ayo Bankole, composed the text and the music of Adura fun alaafia (‘Prayer for peace’), where he raised a number of prayer points that are sine qua non for living in peace within a community. Debo Akinwumi’s Jesu wafara re han (‘Jesus, come and manifest yourself’) is a prayer of blessing and plea for Godly virtues in the life of a newly married couple. The writer believes that Akinwumi was motivated to write the song because building strong families will lead to a strong nation. In an earlier statement which is in agreement with what the above composers did, Leckebusch said, ‘appropriate tune can take words to another level when set to music.’ (source) Adedeji (2017), also noted that, ‘people who normally sing this prayer song are normally satisfied psychologically after singing the prayer song.’

This work is another attempt to encourage more art music compositions that are contextualized for supplicative purposes. The need for supplication should be one of the pre-compositional consideration in the mind of composers of vocal art music in the midst of overwhelming social cultural, economic challenges and the level of insecurity, that the government of the day cannot handle in most nations of the world, particularly Nigeria. It is important to compose music that will meet the supplicative heart desires of the populace.

References

- Adedeji, F. 2006a. “Intercultural Music as Agent of Transformative Musicology.” In Cultura, Culturas. EstudiosSobreMusica, edited by M. A. Ortiz Molina and A.O. Fernandex., 41-54. Granada: Y Education Intercultural, Granada; Grupo Editorial Universitario.

- Adedeji, F. 2010. “Transformative Musicology: Recontextualizing Art Music Compositions for Societal transformation in Nigeria.” In Revista Electronica de Musicologia. Vol XIV.

- Agu, D. 2018. “Compositional techniques and guidelines for the African Contemporary Choral Music Composer.” A Festschrift in Honour of Samuel Olufemi Adedej, 147-155.

- Falola, T. 2001. Culture and Customs of Nigeria. Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Idowu, B. 1962. Olodumare: God in Yoruba belief. London: Longman.

- Johnson-Bashua, A. 2017. “Libation, Homage, and the Power Words.” In Culture and Customs of the Yoruba, edited by T. Falola and A. Akinyemi, 59-68. Austin: Pan-African University Press.

- Nzewi, M. 1984. "Traditional Strategies for Mass Communication: The Centrality of Igbo Music." Selected Reports In Ethnomusicology, 5: 319-338.

- Ofosu, J, 1997. "Modernity and Ovwuvwe: A Socio-Cultural Process of the Abraka Clan in Urhobo Land" in Bode Omojola (ed) Music and Social Dynamics in Nigeria, Ilorin Department of Performing Arts, University of Ilorin. 34-37.

- Ogungbemi, S. 2017. “Traditional Belief System.“ In Culture and Customs of the Yoruba, edited by T. Falola and A. Akinyemi, 309-324. Austin: Pan-African University Press.

- Oludare, O. 2017: “Preserving History Through Popular Music: A study of Ebenezer Obey’s Juju Music.“ West African Journal of Musical Arts Education (WAJMAE), vol. 4(1): 51-65.

- Omojola, O. 2006. Popular Music in Western Nigeria: Theme, Style and Patronage. Ibadan: IFRA.

- Onwuekwe, A. 2016. ”Structural Analysis of Idolor’s ‘Glory Hallelujah to his name’.“ In Music Scholarship and performance challenges in 21st century Africa: A critical sssresource book in honour of Emerobome, edited by K. I. Eni, B. Binebai and S. O. Ikibe. Lagos: Bahiti and Dalila Publishers.

- Randel, D. 1986. The New Harvard Dictionary of Music. Harvard: The Belkarp Press of Harvard University.

- Vidal, A.O. (n.d) “The Development of Church Music in Nigeria: Past, Present and Future.” Unpublished Article, p.1.