#1 Anatomy Of Ethos, Pathos In Music Of Africa and Its Pathogenic Essence

UDC: 781.7(6)

78:316.7

COBISS.SR-ID 59552009 CIP - 4

_________________

Received: Jan 5, 2022

Reviewed: Jan 24, 2022

Accepted: Feb 02, 2022

#1 Anatomy Of Ethos, Pathos In Music Of Africa and Its Pathogenic Essence

Citation: Aluede, Charles O. and Olatubosun S. Adekogbe. 2022. "Anatomy of Ethos, Pathos in Music of Africa and its Pathogenic Essence." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 7:1

Abstract

There is the need to re-examine what was previously held as age-old truths in the light of new findings; the issue of music and its use in our contemporary societies is one of such. For example, there was a general assumption that music making has no side effects and that everyone enjoys music. Today, musicogenic epilepsy stares at our faces and we have come to know that such beliefs are not truly so. Without contradiction, music features in major activities in our daily living. The avenues for music making in traditional societies are gradually being taken over by the churches, club houses, social and cultural organisations with high wattage of volumes. This development has some negative effects on human and environmental health. This study uses a descriptive research method which entails quantitative and qualitative designs. Data were elicited through participant observation, interviews, review of apt literature and questionnaires. A4D Tuner, a tool for measuring sound pressure levels was used to assess the volume of sounds often emitted in certain social and other gatherings. It was observed that most of the musical avenues visited emit sounds which are far above the recommended 75dB as stipulated by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The work predicts that bathing people or the environment with excessively high volume of sounds will in no time engender physical and emotional disturbances, neural deafness and even total deafness. Consequently, it suggests that the government should make adequate legislation on sound pollution to arrest this malaise.

Introduction

Although no one can talk with exactitude, the origin of music, everyone enjoys music making and its concomitant attributes. How music evolved and the actual age of music is not too clear. For an instance, McClellan (2000) observes that in the world’s mythologies, music was either discovered or was bestowed on us by supernatural beings. Henry Farmer in McClellan (2000) further opines that:

the earliest physical evidence of musical activity that we possess, a clay ocarina with five holes, bespeaks an already flourishing music as early as 10,000 B.C. whereas our emergence as specie has been dated to at least one thousand years ago. So too, our earliest civilization has been estimated to have been established no more than 8,000 years ago, yet within them we find evidence of an already flourishing culture where music occupied a well-regulated position in social and religious life of its people. (McClellan 2000, 1)

These gaps notwithstanding, it is generally a known fact that music serves a lot of positive roles in the lives of humans. For example, within the African soundscape, music is known to be made from infancy through adulthood to death. Today, there is a growing need to take a second look at the use of music in our daily activities. No doubt, while the avenues for music making in our traditional societies are waning, contrastingly, music making in the churches, club houses, social/ cultural organisations, and schools is waxing. That the composition of these ensembles' membership is compromised is to say the least. This fundamental compromise begets the kind of music, choice of musical instruments and volume of sound production we are bathed with on a daily basis. These tendencies have their attendant negative effects. Since music is a powerful tool which works on our emotions, and since our emotions have the propensity of controlling our overall well-being, it has become exigent to undertake a seminal study on the pathogenic stance of music in today’s world.

Definition of selected terms

Quite relevant to this paper are three major terms which are considered crucial to be properly defined within the context of the work. This is reasoned vital as it would give us a smooth transition into every segment of this research. From the etymological point of view, Ethos is a Greek word meaning "character" that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology. The Greeks also used this word to refer to the power of music to influence emotions, behaviours, and even morals ([Ethos])(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethos). It is within the latter cusp that we intend to dwell much on. Therefore, to talk about musical ethos, we are without doubt, concerned about the characteristic features, attributes and fundamental values of music as part of any given culture.

In a similar vein, Singer (2013, 209) opines that Pathos plural: pathea or pathê is from a Greek word which means "suffering" or "experience" or "something that one undergoes," or "something that happens to one". Put quite simply, the British online English dictionary defines pathos as the quality or property of anything which touches the feelings or excites the emotions and passions, especially that which awakens the tender emotions, such as pity, sorrow etc. Although of Greek origin, in contemporary parlance, pathos enjoys a kind of duality in arts and medicine. While in arts it is said to touch feelings or excite emotions, according to Singer (2013, 209) Pathos in medicine refers to a "failing," "illness", or "complaint." Stopper (2021), puts it succinctly that Patho, a prefix derived from the Greek "pathos" meaning "suffering or disease, serves as a prefix for many terms including pathogen (disease agent), pathogenesis (development of disease), pathology (study of disease), etc.

Materials and methods

To elicit the relevant and related data which is required in this study, we relied on descriptive research method. This method combines quantitative and qualitative designs. Much attention was given to participant observation in churches, social ceremonies, concerts and club houses. Interviews were conducted and a review of apt literature was done. A4D Tuner, a tool for measuring sound pressure levels was used to assess the volume of sounds often emitted in some selected churches and other social gatherings. These methods of data extraction were enhanced by the use of questionnaires to obtain robust information needed for an encompassing gaze at the Nigerian soundscape.

Music in human life

Though a subject of debate as to when music making began, there are somewhat sacrosanct opinions about music itself and how/when humans get to know musical impulses. There is overwhelming evidence that human beings who are biologically created have had music as part of their creation even before birth. For example, in the opinion of Levitin (2007):

Inside the womb, surrounded by amniotic fluid, the foetus hears sounds. It hears the heartbeat of its mother, at times speeding up, at other times slowing down. And the foetus hears music, as was recently discovered by Alexandria Lamont of Keele University in the UK. She found that, a year after they are born, children recognise and prefer music they were exposed to in the womb. (Levitin 2007, 222)

Levitin is not alone in the position cited above. Parncutt (2016, 220) reports that the acoustical stimulation to which the foetus is exposed to is more diverse and carries more information relative to corresponding discriminatory abilities than visual, tactile or gustatory (biochemical) stimulation. Reporting an earlier investigation, the author opines that “the foetus hears throughout the second half of gestation because, the foetal inner ear is filled with fluid, much of the sound heard by the foetus is transmitted through the skull by bone conduction.” Corroborating this fact was the narration of my wife during the pregnancy of our first child that the baby dances to music in the foetus. This was also confirmed by a Nursing Matron Mrs. Fatuloju of the Anti-Natal Clinic of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife in an interactive interview on May 27, 2021 at the Hospital premises.

Recapitulation

In this segment, we intend to present kaleidoscopic snapshots of resources on music and humans in the last two decades. A terse reprise of previous beliefs by some scholars about the use of music to bring about healing is considered necessary here as this will provide the much needed pivot to latch into the nexus of this study. Within the last two decades, quite a number of voices have attested to the therapeutic potency of music.

Cottrell (2000) remarks that:

Since the beginning of recorded history, music has played a significant role in the healing of our world. Music and healing were communal activities that were natural to everyone. In ancient Greece, Apollo was both god of music and medicine. Ancient Greeks said, ‘music is an art imbued with the power to penetrate into the very depths of the soul’. These beliefs were shared through their doctrine of Ethos. In the mystery school of Egypt and Greece, healing and sound were considered a highly developed sacred science. Pythagoras, one of the wise teachers of ancient Greece, knew how to work with sound. He taught his students how certain musical chords and melodies produce definite responses within the human organism. He demonstrated that the right sequence of sounds, played musically on an instrument, could actually change the behaviour patterns and accelerate the healing process. (Cottrell 2000, 1)

The healing power of music has been recorded as far back as 1500 BC on Egyptian medical papyri (O’Kelly 2002). More recently, there has been a resurgence of music in healthcare brought about by music therapists (Hogan 2003). Furthermore, music has been used for improving physical, psychological and emotional problems during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Europe (Cardozo 2004). The healing powers arising from the mystical intercourse of music and prayer have captured the attention of prophets and poets, scientists and physicians, the lay and the learned alike throughout the ages and across the world. In the present global-cultural milieu, where professional, affordable healthcare is scarce at best for the majority of humanity, where a staggering number of people in the wealthiest country of the world are without basic health insurance, where medical mistakes have become far too numerous, and where an increasing number of individuals are opting for ICAM (integrative, complementary, and alternative medicine) approaches to health care, much can be learned from cultures that have ancient traditions of ICAM healing (Koen,2009, 1). These opinions tend to give much credence to the healing forces of music and a need for an integrative mechanism which will include music and other related arts. In this thinking, Daveson, O’Callaghan and Grocke (2008, 280-281) have identified indigenous music therapy as a platform which encapsulates the roles of the music therapist, the client and the philosophy behind the activity. Music and healthcare have been interconnected from the time of the ancient Greeks (Gallagher 2011). According to Stevens (2012):

Much of the world is singing, dancing and drumming with little concern about whether they have talent or will become famous. Music is woven into the fabric of life in many music cultures; it is an essential medicine for creating joy, gathering community, generating hope, freeing the spirit, communing with the spirit and educating the children. (Stevens 2012, 3) This practice is a common phenomenon in Nigerian societies where there are many avenues for music making and to contain excesses, some genres are regulated by traditional modes of music censorship. That music is a powerful invention which man is constantly exploring is not to be doubted. Its powers have been acclaimed by quite a lot of people and also aptly captured in literature. The views of Koen et al. (2012), and Hanser (2016) are shared below. According to Koen, Barz and Brummel-Smith (2012):

Music is as diverse as the number of people who exist. Throughout history, the potential transformational power of music and related practices has been central to cultures across the planets, and music has been far more than a tool for evoking the relaxation response. It has been a context for and vehicle for expressing the most deeply embedded beliefs and expression of human life and a way to create or recreate a balanced and healthy state of being within individuals, families, and societies. (Koen, Barz and Brummel-Smith 2012, 12)

This claim is further corroborated when it is said that:

Music immerses us in the range of feelings that guides self-discovery along the path to healing. It also anchors us, as we grasp the meaning of music in our lives and create new ways of expressing ourselves. While we access, explore, and communicate the deluge of emotions that can flood us when we are ill, it is possible to become well, even if we are not healthy. Music therapy empowers us to embark on a sacred quest to find the healer within, and come to peace with our physical conditions and their psycho-spiritual concomitants. (Hanser 2016)

In recent times, music as a field of study has become enlarged. Thus remarks Ticker (2017) that:

(...) fields such as music therapy has been expanding and growing. Clinicians are using music in therapeutic settings to help those with brain damage or developmental disorders, especially in regard to children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and patients with traumatic brain injuries. Music is very powerful, and its effects on brain plasticity, cognition, emotion, and physical health have important and valuable repercussions for the field of healthcare. (Ticker 2017, 1)

So far, not much is heard of the negative effect of music making and listening. This palpable silence needs a proper re-examination. The positive attributes of music have been over-flung to the degree of a total brainwash such that there is a general assumption that constant and unchecked music making is advisable. Even in recent times, we still hear that according to O’Connor (2020, 1) music stimulates the brain centres that register reward and pleasure, which is why listening to a favourite song can make you happy. There is in fact no single musical centre in the brain, but rather multiple brain networks that analyse music when it plays, thereby giving music the power to influence everything from our mood to memory.

Humans and Musicing: The need for Caution

That mothers throughout the world and as far back as in time as we can imagine, have used soft singing to soothe their babies to sleep, or to distract them from something that has made them cry (Levitin 2006, 9), and that synchronised singing and dancing did more than just facilitate the building of large- scale civic structures and helped build political structures as well (Levitin 2010), is not sufficient to undermine its side effects.

Early in time, a word of caution was given by Benson (2010, 18), when he observed that not all music has the potential to be healing music. There is rare epilepsy called ‘musicogenic epilepsy’, which is induced by listening to music played by an orchestra, even the sound of the piano or ringing bells can cause an attack on human health if played at an excessive volume that can cause ripples in the human ear. Complementing the effects of high volume of sound on the human ear, Benade (1990, 532) opines that sounds are perceived through hearing, hearing is achieved through the ear and the ear has a threshold of what volume of sound it can accommodate. Any sound beyond what the threshold of the human ear can take is considered as noise. Any sound beyond what the threshold of the human ear can take is considered as noise.

In another subject relating to the perception of musical sound, Smith (1997) observes that:

sound perception in terms of combination of tones, when two tones that are close together in frequency are sounded at the same time, beats generally are heard at a rate that is equal to their frequency difference. In other words, when the frequency difference exceeds 15 Hz, the beat sensation disappears and musical tone roughness appears and this is when musical sound turns to noise. (Smith 1997, 228)

Schaeffer (1991, 266) discovers that the sound processing performed by the ear and the brain is extremely complex, and difficult because it involves subjectivity of hearing, listening, understanding, comprehension of musical sounds. Sound level measurement in church auditoria has to do with sound pressure level (SPL) which can only be determined by use of Sound Meter Reader (SMR) that is commonly used, as postulated by Krug (1993, 25) in the measurement of noise pollution research or investigation that reading from a sound meter does not ascertain the possibilities of accurate facts on how sound is perceived by individual because perception of sound is subjective especially in Africa where sound is arrogated to power and affluence. Adesiya (2005, 42) also argues that if two individuals engage in an argument, the public always has the notion that the higher voice between the two is winning the argument. Objectively, at sixty decibels (60dB), the loudness of sound is still perceivable as approved by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Nagata (2001, 38) posits that in a church auditorium, the perceived sound consists of directly primary radiated sound from the source and reflected sound various surfaces of the hall especially, walls and ceiling. This reflected musical sound is usually confused for reverberation because, the perceived sound consists of both primary and reflected sounds. In this connection, McAdam & Bregman (1979, 28) posit that the primary sound determines the perceived volume level because this is appreciably louder in the sense that sound becomes softer in proportion to the square of the distance traveled and the reflected sound travels a much longer distance, and sound is partly absorbed and diffused by the reflecting surface.

Arising from the above argument, it is opined that all reflected sounds normally play an insignificant position in the real pick out volume level. Thèberge (1999, 69) complements this by stating that primary sound and reflected sound are essentially two separately arriving sounds of different volume levels. In other words, this could be regarded as fundamental and residual musical sounds. Commenting on another characteristic of hearing, Rosch (1978, 548) writes that the combined sounds are perceived as being only as loud as the volume of the two sound-sources. The louder sound determines the apparent volume level; the lower sound does not add appreciably to the perceived volume level. Our daily experience of musical sound perception has put it that larger part of the sound-producing environments are full of sound reflecting materials and substances because one or two of these objects are usually closer to the sound source and that the reflecting surfaces are proportionally much farther away as far as our understanding can guide us. Therefore, this has conditioned our ears to hear but could not distinguish between the fundamental and the harmonics sound where the volume of the reflected sound has some lower decibels than the primary sound.

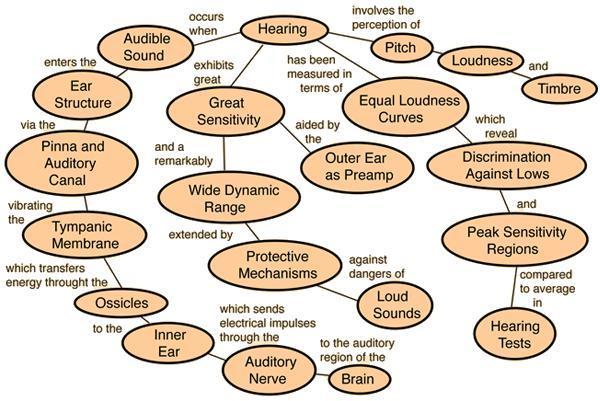

The obvious interaction of the volume of the precise and non-precise musical sound require preservation in order to make musical instruments acoustics in church auditoria natural. The flowing order of sound measurement level as propounded by Georg von Bekessy (1938, 152) using the Place Theory of Sound Perception (PTSP) is seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hearing and perception of sound (Georg von Bekessy 1938, 152)

Measurement of sound pressure level (SPL) requires sound metre readers such as A4 DaTuner in order to provide accurate percentage of produced sound and sound received in connection to the sound producing environment like a worship auditorium. This is a digital process to assist in plotting a graphical explanation of sound intensity, sound frequency and sound decibel.

Concept of Loudness of Musical

Instruments Sounds

Relating to the concept of loudness of musical instruments acoustics, Smith (1997, 243) writes that recent shifts in the aesthetic value of audio loudness is a symptom of broader shifts in attitudes about social harmony and techniques for managing musical sounds and musical acoustics in an auditorium. This may be because of Africans social connection to the overall uproarious sound which is generally shown when two Africans are occupied with a contention or getting a call, anybody standing not many meters away could hear such discussions perceptibly. In this connection, Emielu (2013, 47) opines that in Africa, sound is arrogated to power and the louder the sound, the more powerful the producer of such sound.

Sound has often been used as a channel of oppression, intimidation, challenge and even to create a call for undue attention. This cultural factor is practised anywhere around us in the theatres, concert halls, film houses, churches and even in the hospitals where there should be minimal generation of noise in order not to disturb patients on admission. Aldred (1978, 63) opines that it is interesting to think for a while about the notion of a sound being not loud enough or being too loud, because it appears that these two phrases do not refer to the same concept. Connecting this to this study, a sound may not be loud enough if it is not well heard and may be too loud when it distorts the air. The volume of a television set may not be loud enough if the volume is not audible enough for the viewers to hear and may be too loud if the volume is louder and constituting a noise nuisance to the viewers.

In view of Aldred’s idea, it tends to be reasoned that a sound is not effectively perceptible and difficult to be heard. Along these lines this thought of sound as seen by Vorländer (2008, 120) is similar to intelligibility, rather than acoustical factor. This is a relative notion which holds that sound intelligibility depends on the acoustical environment and background noise,. There are, at least, two different notions regarding loudness (as given by Sandell 1995, 221): one is that a relative notion related to intelligibility, and two, a more absolute one related to an unpleasant or even painful feeling. It is worthy to say that a sound is too loud in the sense of intelligibility. For example, when a television volume becomes an impediment to audibility to a particular conversation in a room, the notion of loudness turns to a multiform, and therefore cannot be mapped to a singular sound volume situation. It could therefore be submitted that the notion of loud musical sound in church auditoria is an emotional factor as worshippers are emotionally attached to church auditorium musical instruments acoustics. Submitting on this, McAdam and Bregman (1979, 40) state that loudness of musical instruments acoustics is not only about objective properties of the external world, but also about our cultural world or more precisely about the effect of sounds on our organism. In addition to this, Sreedhar (2000) puts it that:

many listeners have subconsciously felt the effects of over-compressed songs in the form of auditory fatigue, where it actually becomes tiring to continue listening to the music. ‘You want music that breathes. If the music has stopped breathing, and it’s a continuous wall of sound, that will be fatiguing’ says Katz. ‘If you listen to it loudly as well, it will potentially damage your ears before the older music did because the older music had room to breathe.’ (Sreedhar 2000, 118)

Author’s opinion above suggests an equilibrium position in the musical instruments sound production. The balancing of the high, middle and the low frequencies should produce a well breathing and lively musical sound with no tiring or boring effects on the listeners.

Musical Instruments’ Sounds and Pitch

Pitch in music is considered as the highness or lowness of a musical tone, this is in agreement with its amplitude, length, and colour. Pitch cannot be determined without the frequency and a precise scientific unit of decibel measurement. Gade (1985, 112) observes that pitch is equally affected by individual personal opinion that takes into consideration the comparative placement of highness or lowness of musical instruments acoustics within church auditoria especially during a worship service. Olson (1971, 13) observes that pitch is determined by the frequency of sound. However, this could be used in the balancing of musical instruments' sound production in a situation where there is a war of sound or a conflicting emanation of musical instruments’ sounds pitch from a live source. The application of pitch analysis in church auditoria will reduce the effects of loud musical sound productions on the congregation and also make clarity of musical sound possible. The traits of conflicting musical sound production were experienced in virtually all the purposively selected sound producing auditoria case-studying for this research.

Our observations on the nature of musical instruments’ sound productions in the selected church auditoria signal serious health implications on the congregation especially, young babies whose parents are ignorant of this great health hazards of exposure to amplified music and loud musical sounds. Ameye (2018) observes that:

long hours of loud sound exposure can result in partial deafness of the choir, the instrumentalists, the ministers and the entire congregation. More often, people in this category undergo unpleasant hearing sensations triggered by noise pollution through heavy wattage of musical instruments’ sound. ( Ameye 2018, 15)

The above submission attests to the researcher’s experience in all the selected church auditoria in south-western Nigeria. It is very important to possibly avoid exposing young and old to loud musical noise especially, during worship sessions.

Musical Instruments’ Sounds and Frequency

Frequency of musical instruments’ acoustic in any auditorium comprises of compressions, diffractions and refractions of a medium. However, Brown (1992, 139) observes that in musical instruments’ sound productions, using the unit of Hertz (Hz) as frequency measurement, frequencies tend to take up a wider frequency range, because the sound waves excite more ears when the perception of a sound is diminished by a louder sound. In another account, Bruce (1997, 182) writes that higher frequency sounds tend to be more precise in this sense. The graphical demonstration (Figure 2) addresses the behaviour of cycle per second movements of sound frequency in musical instruments’ acoustic and sound productions as provided by Bruce.

Figure 2. Difference in wave length between 1 Hz and 10 Hz. ( Bruce 1997)

Relating this to musical instruments’ production in church auditoria, one would begin to think about the frequency spectrum of each musical instrument and which musical instrument is masking the other musical instruments in an ensemble. This phenomenon was experienced at the Celestial Church of Christ (CCC), Akobo, Ibadan, where the church sound engineer, due to his lack of experience, put all the available musical instruments at the same high and low frequencies which results to non-clarity of sound production. It should be noted that the lead guitar has a different frequency from the keyboard, the bass guitar is a low frequency instrument, the saxophone is a high frequency instrument and the trumpet, a high frequency musical instrument, all these musical instruments were set to the same volume. In this context, panning, which is a process applied on the console mixer to synthetically proportion each musical instrument’s sound in a stereo mix in order to provide a distinctive sound to allow for a good musical sound perception was neglected. The frequency spectrum of each musical instrument and how such sound is produced through the process of amplification, in the Front of House Speakers (FOHS) should be of great concerns to church sound engineers. The graphical expression of high and low musical instruments is represented in the Figure 3:

Figure 3. Graphical expression of low and high frequencies of musical instruments

Musical Instruments and Acoustic Peculiarity in Church Auditoria

Every musical instrument has its own peculiar acoustic nature which gives the fundamental vibrations to produce sound. Ancient or Modern, African or Western musical instruments are made with certain acoustic considerations. A number of researchers such as Hast (1989, 120), Fitch (1997, 215, Fitch (1999, 520), Riede and Fitch (1999, 257), Fitch and Rebv (2001, 167), and Rebv and McComb (2003, 522), have studied the sound production techniques of musical instruments. Also, Benade (1976, 190) and Hutchins (1980, 185) have commented on the musical instruments acoustics and sound quality subjectivity in the areas of timbre, loudness and pitch. Recently, large concentrations are directed at the digital process, through the use of computers, in the production of synthesized musical instrument sound and notational music composition. As a result of the emergence of personnel with training and experience in musical acoustics in the entertainment industries, in education, in recording and film studios, or in the musical instrument industries who are not ready to leave their job for church’s job, has left churches with little percentage of music professionals in church’ sound productions and management.

Allard and Atalla’s (2009, 245) opinion might be right on how the musical instruments produce sound without the process of vibrations but still not addressing how human beings produce sound through the vibration of the body. Though, having knowledge of the instinctual foundation of musical instruments’ sound productions are used in the production of musical notes and sounds, this is required to provide physical criteria to distinguish between satisfactory and non-satisfactory musical instruments’ sound. It could have been very necessary to discuss the musical audibility of each class of musical instruments found in the selected church auditoria for this study but, due to the limitations of the study’s theoretical framework, it would be very difficult to discuss how each musical instrument produce sound and how each production can be extremely complex. This may require applying other theories outside the thesis’ theoretical framework. For example, Turbulence theory of irregularity and unpredictability by Zwinglio (2008, 112) would have been used to describe the fluctuation in the movement of air production of certain aerophones musical instrument.

Elements of Musical Instruments’ Sounds in Church Auditoria

Richard (1988, 315) opines that musical instruments’ acoustic in church auditoria is a reflection and expression of the individual’s mind which are subjective to how individual perceives musical sound. In his assertion, he states that:

(...) music has an estimable ability to deliver and act for the mind, more intuitively than any other sensual mean, the very standing, rising and falling, the very steps and inflections every way, the turns and varieties of all passions whereunto the mind is subject; yea so to imitate them, that, whether it resembles unto us the same state wherein our minds already are (...). (Richard 1988, 315)

From the above, it could be deduced that musical activities in church auditoria should be of the highest quality. It should be as a rule, especially for Church worship to pass desired messages that are meaningful to the worship participants. Much of musical activities as practiced and perceived in the selected church auditoria do not agree with Richard’s attestation. Musical activities in many cases amount to noise pollution. Making music in church auditoria could been seemingly analogised to a story book with spelling mistakes on every page yet, musical instruments with unbearable high wattage of volume are still allowed and accepted and even tolerated as a result of ignorance on the part of Church administrators and worshippers alike.

The Sensation of Loudness

The human ear has a limited decibel of sound reception in terms of loudness and volume level. Barron (2005) writes on the sensation of hearing that:

When pressure fluctuations reach the human ear, this occurs in a certain frequency region, and does not fall below a minimum sound level. The lowest frequency for which a vibration process is still perceived as a tone is approximately 16 Hz. This corresponds to a Cₒ which is included in the 320 register of some large organs. For yet lower frequencies, the ear can already follow the temporal process of the vibrations, so that a unique tonal impression can no longer be formed. Barron (2005, 577)

From the above submission, Barron’s position is clearly understood that it is likely that hearers of musical sound can lose tonal registration if certain musical sound is higher in volume than the human threshold of hearing. In this context, Sessler, Schultz and Watters (1991) also submit that:

(...) this so-called threshold of hearing depends in large measure on frequency. The ear responds with most sensitivity to tones in the frequency range between 2,000 and 5,000 Hz. In this range, the minimum required sound level is the lowest. For higher frequencies, but even more so for lower frequencies, the sensitivity of the human ear is reduced, so that in these regions significantly, higher sound pressure levels are required for a musical tone to become audible (...). (Sessler, Schultz and Watters 1991, 885)

The author’s position is slightly different from earlier position that, if the threshold of hearing depends on the measurement of sound regular occurrence, the ear will respond to the most sensitive sound is a generalised statement and of course, is not binding on all sound hearers. Hearing musical sound, either at low, middle or high frequencies, will affect the threshold of hearing, if the volume is grater or higher than what the human hear can tolerate. Patynen (2009) in his submission categorically states that

the same tendency is evident when at higher intensity of tones of different frequencies are compared in relation to their impression of loudness. The sound pressure level as an objective measure of existing physical excitation is by no means equivalent to the loudness as a subjective measure of sensation. Patynen (2009, 877)

From Patynen submission, it is deduced that objectivity and subjectivity factors in musical sound perception cannot be ruled out. The impression of musical sound loudness is not a general concept, what is loud to A might not be loud to B in terms of musical instruments sound productions and perceptions. In a supportive argument, Ikibe (2010, 207) views the sensation of loudness of musical instruments sound as experienced in worship auditorium from a different position. Ikibe argues that the high level of musical acoustics in church auditoria could be likened to a musical sound in a disco hall. Ikibe’s opinion was based on his experience at the Redeem Christian Church of God, Kwara Provincial Council. The level of loudness of the musical production was high and this triggered the secularization of the dance steps of the choir which made the ladies to shake their buttocks in the manner of a disco hall dance as observed at Celestial Church of Christ, Ibadan and Saint Peter’s Cathedral Church, Ake, Abeokuta.

Analysis of Findings

Resulting from participant observation in all the selected auditoria, it was found out that the performance space for musical activities is a major factor in musical sound acoustics and sound propagation because of the tonal colouration and reverberation provided by the selected auditoria. Realistically, reflections from the solid flat areas of walls in the selected auditoria affect the total propagation of sound. It was also discovered that the amount of sound scattering depends on the rate of occurrence of the waves of sound, the reflective materials and at the same time, the lower rate of sound occurrence is also likened to the dimension of the sound reflective objects, this suggest that the musical sound does not only reflect from the flat walls, but also experiences refraction as the musical sound waves increases in length and changed in its directional propagation in a non-complete and curving round the reflective objects within the auditorium.

On the measured sound decibel in the selected sound producing auditoria, the paper finds out that there were different four musical sound volumes perception per each auditorium. However, in this observations and measurements, five different variables such as sound reverberation, sound clarity, pitch, sound frequency and sound volume were considered as connected with musical sound in its transmission, reception and perception by the people within the acoustic nature of the selected auditoria. The Place Theory of Sound Perception (PTSP) emphasises how human ear perceives and interprets sound. It is on this theoretical framework that this study looks at the perceived number of decibels in the selected indoor and outdoor venues to be on the minimum of 105dB and maximum of 109dB and the average of 107dB. Qualitative results of the measurement of musical instruments sound in all the selected church auditoria are summarised in Table 1.

| Auditorium | Average Decibel | Average Decibel | Average Decibel | Average Decibel per Auditorium | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christ Apostolic Church Headquarter, Ile-Ife | Day One-104 dB | Day Two-105 dB | Day Three-102 dB | 104 dB | Very high |

| Saint Paul Cathedral, Yemetu, Ibadan | Day One-100 dB | Day Two-105 dB | Day Three-103 dB | 103 dB | Very high |

| Ogunbanjo Event Hall, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife. | Day One 112 dB | Day Two-110 dB | Day Three-109 dB | 110.33 dB | Very high |

| MTN Talent Hunt Show (May, April 10, 2021) Freedom Park, Lagos | 117.18 dB | One Measurement | One Measurement | 117.18 dB | Very high |

| Average Musical Instruments Acoustics Volume | Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Average dB | |

| 108.25 dB | 107 dB | 105 dB | 109 dB | Very high | |

| Average of Noise Level in All the Selected Church Auditoria | Minimum LAeq,T | Maximum LAeq,T | Average LAeq,T | ||

| 105 dB | 109 dB | 107 dB | Threshold of Pain | ||

Conclusion

This article on musical sound in selected auditoria has examined the generation, transmission, reception and perception of musical sound. It has applied the Place Theory of Sound Perception (PTSP) by Georg von Bekessy (1938). The theory was concerned with how sound is perceived and analysed by the human ear. Serious attention has been drawn to an emerging and important area of discourse in the arts, humanities and the environment especially, with regards to musical sound productions, propagation and perception and the nature of acoustics parameters of the selected sound producing avenues. The paper takes into cognisance the various musical attitudes of people in churches and other social gatherings with regards to available musical sound productions. The study further investigates how human perceive musical sound in each of the selected avenues in relation to sound production in order to establish who perceives what at a particular seat location within the church auditorium. There is a need to join thoughts with the views of Roseman (2012):

Medical ethnomusicology, or the study of music, medicine and culture, has the challenging task of living at this juncture. Can we remain socio-historically specific and cross-culturally resonant, as anthropologists and musical ethnographers try to, while being clinically relevant and bio-medically viable, as social activists or medical clinicians might desire? It seems to me that to further this endeavour, it would be useful to learn each other’s languages. (Roseman 2012, 19)

This paper establishes that loud musical sounds coming out from each worship and social gathering are subtle agents to reducing the lifespan of those who are religiously, socially or culturally, coupled with ignorance, attached to loud musical sounds and its amplified productions from which are likely to suffer great consequences. The study further observed that loud musical sounds in the form of noise pollution from such avenues have been ignored and have made our society become very noisy. It is therefore concluded that musical sound and its amplified sound produced in the selected avenues are actually more than the recommended sixty decibels (60dB) by the World Health Organisation (WHO) for a normal human ear.

References

- Adesiya, M. 2005. An introduction to music management. South Africa: Dolly Publishers Limited.

- Adekogbe, O.S. 2021. "A Study of Musical Instruments' Acoustics in Selected Church Auditoria in South-western Nigeria." Ph.D. Dissertation (Unpublished), Department of Performing Arts, Faculty of Arts, University of Ilorin, Nigeria.

- Aldred, John. 1978. Manual of sound recording. Fountain Press Ltd.

- Allard, J. and Atalla, N. 2009. Propagation of Sound in Porous Media: Modelling Sound Absorbing Materials. 2e. Wiley Publishers. ISBN: 978-0-470-74661-5

- Ameye, O.S. 2018. “Time-domain simulation of sound production in the brass Instrument.“ Journal of Acoustics Society of America (32): 10–23.

- Ballou, G. M. 2005. Handbook for Sound Engineers. Elsevier science and technology Ltd.

- Benade, A.H. 1976. Fundamentals of Musical Acoustics 1. London and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Benade, A.H. 1990. Fundamentals of musical acoustics 2. London: Oxford University Press.

- Benson, Stella. 2010. The Healing Musician: A Guide to Playing Healing Music at The Bedside. ISBN 0967545307

- Bregman, A. 1979. “Hearing Musical Streams.” Computer Music Journal Vol. 3(4): 26-43+60

- Brown, S.D 1992. Time-domain simulation of sound production in the brass instrument. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Bruce, S.W. 1997. “Pitch discrimination of diotic and dichotic tone complexes: harmonic Resolvability or harmonic number.” Journal of Acoustics Society of America (3): 179-189.

- Cardozo, M. 2004. Harmonic sounds: complementary medicine for the critically ill. British Journal of Nursing 13 (22): 13-214.

- Cottrell, Amrita. 2000. What is Healing Music? A closer look.

- Daveson, B., O’Callaghan, C. & Grocke, D. 2008. “Indigenous music therapy theory building through grounded theory research: The developing indigenous theory framework.“ The Arts in Psychotherapy (35): 280–286.

- Emielu, Austin Maro. 2013. Nigerian Highlife Music. Lagos: Centre for Black and African Arts. ISBN: 9785115615

- Fitch, G. F. 1997. Studies in Musical Acoustics and Psychoacoustics. Current Research in Systemic Musicology 1. Springer International Publishing Company.

- Fitch, G. F. 1999. Studies in Musical Acoustics and Psychoacoustics. Current Research in Systemic Musicology 2. Springer International Publishing Company.

- Fitch. G.F. and Reby, D.A. 2001. Aspects of Tone Sensation. London: Academic Press.

- Gade, A.C S. 1981. Musicians Ideas about Room Acoustical Qualities. DTU. Report No. 31. Kongens Lyngby, Denmark: The Acoustics Laboratory. Technical University of Denmark.

- Gallagher, L. M. 2011. “The role of music therapy in palliative medicine and supportive care.“ Seminars in Oncology 38(8): 403-6. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.03.010

- Georg von Békésy 1938. Audiology and the cochlea. London: Mayo Clin. Publisher.

- Hast, W. D. 1989. The Hearing of symphony orchestra musicians. Scand.: Audio Publisher.

- Hanser, S.B. 2016. Integrative Health through Music Therapy: Accompanying the Journey from Illness to Wellness. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Hogan, B. 2003. “Soul Music in the Twilight Years.” Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation 19(4): 275–81.

- Hutchins, E. 1980. Culture and inference: A trobriand case study. Harvard University Press.

- Ikibe, S. 2010. “Religious transformation: Critical issues in the secularization of Gospel music in Nigeria.“ A paper presented at The Crossroads in African Studies Conference (Brazilafrica). The Department of African studies and Anthropology centre of West African Studies, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom.

- Koen, B.D. 2009. Beyond the Roof of the World Music, Prayer, and Healing in the Pamir Mountains. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Koen, B.D., Lloyd, J., Barz, G. and Brummel-Smith, K. 2012. “Introduction: Confluence of Consciousness in Music, Medicine and Culture.” In The Oxford Handbook of Medical Ethnomusicology, edited by B. D. Koen, J. Lloyd, G. Barz, and K. Brummel-Smith, K., 3 - 17. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Krug, K.H. 1993. Assisted resonance in the royal festival. London: Thomas Telford Ltd.

- Levitin, D. J. 2007. This is Your Brain on Music. New York: Penguin Group

- Levitin, D. J. 2010. The world in Six Songs. New York: Aurum Press Limited

- McAdams, S. and A. Bregman. 1979. “Hearing musical streams. Computer Music.” Journal of Vibrations and Sound (13): 26- 60.

- McClellan, R. 2000. The Healing Forces of Music. New York: Excel Publishers.

- Nagata, Kazunao. 2001. “The World of Electronic Sound 2. (In Concert 1996 & 1997).“ Nagata Sound Magazine.

- O'Connor, M.E. 2020. Music as Medicine: The Healing Power of Music.

- Olson, H. F. 1971. Modern sound reproduction. Van Nostrand Reinhold 2. Aufl. New York.

- Parncutt, R. 2016. “Prenatal Development and the Phylogeny and Ontogeny of Music.” In The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology, edited by S. Hallam, I. Cross, and M. Thaut, M. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Patynen, L. 2009. Subjective reverberation time and its relation to sound decay. New York: Academy of Sciences.

- Reby, D. A. and G. Mc Comb. 2003. “Community annoyance and sleep disturbance: Updated Criteria for Assessing the Impact of General Transportation Noise on People.” Noise Control Engineering Journal (12): 520-532.

- Richard, H. 1888. The works of Richard Hooker, vol. 1. London: Richard Hooker Press.

- Riede, T. and T. Fitch. 1999. “Vocal tract length and acoustics of vocalization in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris).“ Journal of Experimental Biology (202): 2557-2567.

- Rosch, E. 1978. “Synchronization in performed ensemble music.” Acustica 43, 121-130.

- Roseman, M. (2012) “A Fourfold Framework for Cross-Cultural Integrative Research on Music Medicine.” In The Oxford Handbook of Medical Ethnomusicology, 18-45. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sandell, G. J. 1995.”Roles for spectral centroid and other factors in determining blended Instrument pairings in orchestration.” Music Perception (13): 209-226.

- Schaffer, A. H. 1997. “Noise and its effects.” Administrative Conference of the United States. Journal (ACUSJO). (4): 47-55.

- Sessler, G., T. J. Schultz, and G. B. Watters. 1991. ”Propagation of Sound Across Audience Seating.” Journal of Acoustics Society of America (36): 885-897.

- Smith, J. D. 1997. ”The place of musical novices in music science.” American Journal of Music Perception (14): 243-263.

- Smith, J. D. 1997. “The place of musical novices in music science.” American Journal of Music Perception (14): 243-263.

- Singer, P.N. 2013. Galen’s Psychological Writings.

- Sreedhar, B. 2000. Macrofouling in unidirectional flow: Miniature pipes as experimental models for studying the interaction of flow and surface characteristics on the attachment of barnacle, bryozoan and polychaete larvae. Marine Ecology Progress Series 207:109-121. DOI: 10.3354/meps207109.

- Stevens, C. 2012. Music Medicine. Colorado.

- Stopper, M.C. 2021. “Medical Definition of Patho.” Medterms Medical Dictionary a-z list.

- Thèberge, P. 1999. Any sound you can imagine: Making Music /Consuming technology. Book 2. Middletown Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

- Ticker, C. S. 2017. "Music and the Mind: Music's Healing Powers." Musical Offerings Vol. 8(1): 1. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2017.8.1.1. [link]

- Vorländer, M. 2008. Auralization: Fundamentals of Acoustics, Modelling, Simulation, Algorithms and Acoustic Virtual Reality. Springer Publishers. ISBN 978-3-540-48830-9

- Zwinglio, C. R. 2008. ” Music stage design.” Journal of Sound Vibrations (69): 108-122.