#2 The Impact Of The Use Of Code-Mixing In Nigerian Gospel Music

UDC: 783.2(669.1)

COBISS.SR-ID 59565577 CIP - 2

_________________

Received: Jan 15, 2022

Reviewed: Jan 27, 2022

Accepted: Feb 08, 2022

#2 The Impact Of The Use Of Code-Mixing In Nigerian Gospel Music

Citation: Alemede, Emmanuel O. 2022. "The Impact of the use of Code-Mixing in Nigerian Gospel Music." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 7:2

Abstract

This paper aims to evaluate the performance and development of the gospel music industry in Nigeria. It investigates the following assumptions: (i) multilingual songs are more popular than mono-lingual songs; (ii) multi-lingual music bring about unity among different ethnic groups; (iii) multilingual artistes are more popular than mono-lingual artistes, and (iv) multilingual artistes have a greater reach than mono-lingual artistes. Primary data were obtained through a structured questionnaire administered online. Secondary data were collected from national and international journals and books. Data from the survey was analyzed using descriptive statistics of means and standard deviations. The result shows that artists whose songs are multilingual accomplish more in terms of personal development and monetarily. It was also discovered that artists who sing multi-lingual songs have a greater reach than mono-lingual artists. In uniting various ethnic groups, they make their tunes vital, and they gain more attention than artists whose songs are mono-lingual. The paper concludes that as a multilingual song has a great positive effect on the artist, their audience, building a bridge across the divide, and accelerating the growth of the gospel music industry. Hence, the gospel artist should create more multilingual songs.

Gospel music, Christian Music, Cultural-divide, multi-lingual artists, bilingual/multilingual gospel tunes, code-mixing, Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa

Introduction

Gospel music as a genre is associated with Christianity, and hence, a form of religious music. Gospel music consists of glad tidings from religious doctrines which embrace the teaching of Christ. Thus, gospel music touches on several Christian themes such as repentance, victory, deliverance and baptism. It is hard to underestimate the value of gospel music in comparison to other musical styles. It is the oldest style of music from the time of creation and has developed over the ages.

The highest mission of gospel music is to serve as a link between God and man. Throughout the Old Testament, music was an integral part of the worship of God. In the New Testament text, several hymn fragments are present, an indication that shows that the early church relied on hymns and songs to help express the message of Christ's Gospel. There were hymns and choruses/praises in the churches, regardless of denomination, before 1900. It was generally known as Christian music. Over the years it has developed alongside other musical styles like blues, reggae e.t.c.

Daramola (2008) in his introduction on Christian Music as a Discipline: A Religious Appraisal of Christian Music in Nigeria Today quoted Echerua’s assertion (1977) that:

Christianity as a religion has music making as one of its practices from inception. During worship or services, music plays important roles. Any Christian worship or service without music is just like a rainbow without colours. Take away singing from the church and the pews will be vacant and innumerable music halls and entertainment houses will sprout up. (Daramola 2008)

It is possible to view the development of Gospel music in Nigeria from various angles as it relates to the cultural divide beyond being linguistically tribal yet linguistically cutting. The Nigerian gospel music code-mixing is usually put together to encourage such multiple responses.

For many decades, gospel music songs are majorly in mono-lingual form with very few artists or group of choristers having one or two numbers in other Nigerian languages. The peculiarity of some audience is a determinant of the language in which artist sings with. Level of education and enlightenment of some gospel artist is another factor among others for having more of mono-lingual songs between 1900 and 2000. Geopolitical zones affiliation also contributed to the large mono-lingual singing style that lasted for some decades.

In any case, code-mixing in the notable music industry has been remarkable, a situation that has being changed by the advancement of bilingual/multi-lingual gospel tunes. In any event, code-mixing was significant in the remarkable music industry. This is a state of affairs that changes with the promotion of bilingual gospel tunes expressing modernity and sophistication.

Literature Review

Cultural-divide

The virtual barrier created by cultural differences, hindering interactions and cohesive exchanges between people of different cultures, is a cultural divide. Cultural-divide studies typically concentrate on the identification and bridging of the cultural gap at various levels of society. Nigeria is a nation in Africa with, one of the highest ethnic groups occupying the different geopolitical zones. Within each ethnic group, there exist diverse languages with different cultures peculiar to them bringing about the cultural divide but a situation that music is gradually bridging the divide through different musical genre. The individual cultural differences are reflected in the mono-lingual musical style.

Mono-lingual

A community is said to be monolingual when only one language is spoken functionally across all domains of language use in that community. People become monolingual, for example, when the social group they belong to constitutes a numerically powerful group, and their language is the dominant language in a neighborhood where the other languages belong to numerically weaker (i.e. minority) groups. That is, this is when one is a speaker of a dominant language and the dominant language is the language used in all social domains in a given speech community.

Also mono-lingualism is promoted by the fact that individuals belong to and speak the language of the most politically and/or economically powerful group, or the elite group in a given social domain. Language shift leads to mono-lingualism. Language shift is when individuals or whole groups of speakers of a language give in their language in favor of the language of their new or neighboring environment. For example, when people migrate to new places that have one dominant language, they often learn to use it across many domains, and it is often the case that their grand-children (if not even their children) tend to shift completely to the dominant language, thus failing to be bilingual like their parents.

Code mixing

Code-mixing in songs is different from code-mixing in conversation. Bdulkhaleg (2014) cited Myers-Scotton (2006) who affirmed that Code mixing/switching is a research area that is gaining momentum over the past couple of decades. As for the various functions and uses of the phenomenon of code mixing/switching a lot of research has been probing the question of why would people employ such a strategy (Abdulkhaleq 2014). Moyo, T. (1996) argued that the people code switch more when they are competent users of at least two languages drawing on the phenomenon as practiced in South Africa. Sumarsih (Sumarsih et al. 2014) opines that code -mixing is used as gap fillers to ease communication or to sound cool while Liadi and Omobowale (2011) say that hip hop musicians in Nigeria alternate various Nigerian languages in their songs in order to engage in social dialogue with their audience, a situation that enables them to address social issues which English may not adequately address.

Code-mixing uses several languages in one clause or the mixing of different linguistic units from two grammatical systems involved in a sentence. Code mixing also occurs when the people integrate small units from one language to another one. Grammatical rules restrict this intrasentential mixing and can be subjected by social and psychological influences. It also means moving linguistic units from one code to another. Code-mixing is a process that can result in mixed varieties of code.

Methodology

Primary data were obtained through a structured questionnaire administered online. Secondary data were collected from national and international journals and books. Data from survey was analyzed using descriptive statistics of means and standard deviations.

Theoretical framework

This paper is anchored on two theoretical frameworks which are the Theory of Performance (ToP) as propounded by Elger (2007) and Psychological Acculturation Theory as coined by Graves (1967). The former explains that performance develops and relates six foundational concepts to form a framework explaining performance and performance improvements. He explains further that to perform is to produce valued results. A performer can be an individual or a group of people engaging in a collaborative effort. Developing performance is a journey, and the level of performance describes the location in the journey. The current performance level depends holistically on six components: context, level of knowledge, levels of skills, level of identity, personal factors, and fixed factors. Graves (1967) describes acculturation as the process of incorporating the changes that an individual experience in terms of their attitudes, values, and identity resulting from being in contact with other cultures. These two theoretical frameworks will be looked at from and within musical perspective.

Findings and discussion

| Parameters | Classification | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| What do you do in gospel music? (tick as appropriate) | Gospel Musician | 37 | 37.0 |

| Backup Singer | 18 | 18.0 | |

| Instrumentalists | 18 | 18.0 | |

| Listener | 27 | 27.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 15 years - 30 years | 33 | 33.0 |

| 31 years and above | 67 | 67.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 |

Data in Table 1 revealed that the highest percentage (37.0%) of the respondents were gospel musicians, closely followed by 27% who were listeners, while 18.0% were backup singers and instrumentalists respectively. Majority (67.0%) of the respondents were 31 years of age and older, while 33.0% of the respondents were youth from 15 to 30 years of age.

| Parameters | Classification | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is your mother tongue one of the Nigerian languages | No | 2 | 2.0 |

| Yes | 98 | 98.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

| Are Multi-lingual songs preferable than mono-lingual? | No | 31 | 31.0 |

| Yes | 69 | 69.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you think Multi-lingual songs | No | 45 | 45.0 |

| Yes | 55 | 55.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you think multi-lingual songs | No | 48 | 48.0 |

| Yes | 52 | 52.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you think Multi-lingual songs | No | 24 | 24.0 |

| Yes | 76 | 76.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you think multi-lingual artistes | No | 40 | 40.0 |

| Yes | 60 | 60.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you think Multi-lingual artistes | No | 31 | 31.0 |

| Yes | 69 | 69.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you still relate with | No | 7 | 7.0 |

| Yes | 93 | 93.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you think multi-lingual artistes | No | 38 | 38.0 |

| Yes | 62 | 62.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

| If yes, why? if No, Why? | No | 61 | 61.0 |

| Because they perform everywhere | 6 | 6.0 | |

| They reach out to every one irrespective of their language | 14 | 14.0 | |

| Found more meaning than just singing with only one language | 1 | 1.0 | |

| Larger fan base | 12 | 12.0 | |

| They make more sales | 6 | 6.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you think Multi-lingual songs | No | 26 | 26.0 |

| Yes | 74 | 74.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | |

Do you think Multi-lingual songs | No | 37 | 37.0 |

| Yes | 63 | 63.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 |

Data in Table 2 revealed that the majority (98%) of the respondents agreed that their mother tongue is one of the Nigerian languages, while 2.0% disagreed. There are three officially recognized ethnic groups in Nigeria. They are Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa representing the six geopolitical zones in the country. Each of the zones has both official and general language and mother tongue spoken in each of the zones dividing each into different units based on their spoken language and landmass. The official lingua franca in Nigeria is English while other languages are known as Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa, as well as the Pidgin as the commonly spoken and understood local form of English. The majority of the respondents agreed that their mother tongue is one of the Nigerian languages which could fall under any of the languages found in the six geopolitical zones covered/represented by the Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa languages. The percentage of those whose mother tongues are not among the Nigerian languages are likely to be foreigners who are residents in the country.

The highest percentage (69.0%) of the respondents said that multi-lingual songs were more preferable than mono-lingual while 31.0% disagreed. Multilingualism practice generally develops cross-linguistic communication strategies like code-switching and code-mixing (Okal 2014, 256). It also increases the participation of the audience from a different socio-linguistic background.

The highest percentage (55%) of the respondents agreed that multi-lingual songs feature prominently in church worship compared to monolingual songs while 45% of the respondents disagreed. 52% of the respondents agreed that multi-lingual songs were more popular than mono-lingual songs, while 48% of the respondents disagreed.

The table further reveals that the majority (76%) of the respondents agreed that multilingual songs engendered unity among different ethnic groups while 24% disagreed. According to Mithen (2006) there are noticeably variances between music and language, these two spheres share some cohesion such as symbols, grammar, and information transmission. Stein-Smith (2017, 49) opines that multilingual advantage includes foreign language skills, intercultural and international awareness and knowledge, appreciation and understanding of other cultures, the critical thinking, analytical, and communicative skills that are among the learning outcomes of foreign language education in alignment with the goals of "trans-lingual and transcultural competence" as articulated in the report of the MLA Ad Hoc Committee on Foreign Languages, chaired by Mary Louise Pratt, originally published in Profession under the title Foreign Languages and Higher Education: New Structures for a Changed World (MLA 2007).

Sixty percent of the respondents agreed that multi-lingual artistes are more popular than mono-lingual artistes while 40% also disagreed. It is similar to the report of Babalola and Taiwo (2009, 1) that Code-Switching in Nigerian hip hop is used to create unique identities which have positive local and global influences for music and artists and reflect the ethno linguistic diversity of the Nigerian nation. It is an indication of growth in the gospel music industry.

The highest percentage (69%) of the respondents agreed that multi-lingual artistes had a wider reach than mono-lingual artistes, while 31.0% of the respondents disagreed with the assertion. The highest percentage (93.0) of the respondents, still related to multi-lingual songs, even when some of the lyrics were not in a known dialect. While 7% of the respondents didn’t relate to multi-lingual songs. Sixty-two percentage from the respondents agreed that multi-lingual artistes were more successful financially than mono-lingual artistes while 38% disagreed. It is in line with the belief of Babalola and Taiwo (2009, 4) that artistes who seek commercial success within the large market of popular music use code-switching as a stylistic innovation in their song lyrics. An indication that multi-lingual songs are sold in larger quantity and have more audience. Seventy-four percentage from the respondents agreed that multi-lingual songs were more inspiring than mono-lingual songs, while 26% disagreed. The highest percentage of the respondents agreed that multi-lingual songs should be produced more than mono-lingual songs, while 37.0% disagreed. The increase in the production of more multi-lingual songs, will not only bring about popularity for the music and the artists, but the gospel music industry will continue to grow, and, above all, it will further unite the people both at home and abroad.

| Parameters | Classification | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

In your candid opinion which of the | Yoruba and English | 26 | 26.0 |

| Igbo and English | 20 | 20.0 | |

| Hausa and English | 8 | 8.0 | |

| Yoruba and Igbo | 7 | 7.0 | |

| Hausa and Igbo | 1 | 1.0 | |

| Any of the Above and Pidgin | 23 | 23.0 | |

| Three or more combinations | 15 | 15.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 |

The data in Table 3 reveal that twenty-six percentage (26%) of the respondents believe that Yoruba and English as lingua franca are mostly combined in multi-lingual gospel songs, while twenty-three percentage (23%) of the respondents state that any of the above languages and Pidgin are the lingua franca, 20% agree that lingua franca are Igbo and English, 15% of the respondents opine that three or more combinations are the lingua franca which are mostly combined in multilingual gospel songs, 8% hold Hausa and English, and 7% Yoruba and Igbo, while 1% of the respondents declare Hausa and Igbo as lingua franca. The above result based on the best language combination shows that there is a situation where more than two languages are (functionally) used in society because several people know all or a combination of them which is known as Societal multilingualism. Mithen (2006) describes both language and music as “combinatorial systems” which contain acoustic elements such as words and tunes. According to Kuponiyi (2013) whose opinion about hip hop music in Nigeria can be adopted also as a common factor responsible for the twenty-six percentage (26%) of the respondents who chooses Yoruba and English as lingua franca mostly combined in multilingual gospel songs. He stated that:

Although Yoruba is just one of the three major languages in Nigeria, it is the most used by Nigerian hip hop artists. When we listen to Nigerian hip hop songs, we will discover that majority of the artists use Yoruba as part of their language(s) of composition. Not all these artists are Yoruba by origin; most of them acquired the language while growing up. (Kuponiyi 2013, 36)

Majority of the artists either find their way to the big cities like Lagos, Abuja where the majority of their fans resides or they were born and brought up in these cities just like hip hop artistes as asserted by Babalola and Taiwo (2009) that:

While not all artists are Yoruba by origin, they have acquired the language while growing up in Lagos which is a major Yoruba city and the former capital of Nigeria. It is in Lagos that most hip-hop fans reside and most hip-hop activities take place. (Babalola and Taiwo 2009, 9-10)

This assertion is also applicable to other musical genres which have brought development to the musical industries because these cities like Lagos have the highest convergence of people from different ethnic groups in Nigeria.

| Artiste | Song title | Code–mixing Language |

|---|---|---|

| Nathaniel Bassey | Onise Iyanu | Yoruba/English |

| Tim Godfrey | Hallelujah | Yoruba/English |

| Frank Edward | Lifted | English /Igbo/Ibibio |

| Chioma Jesus | Okemmuo | Igbo/English |

| Prosper Ochimana | Ehwueme | Igbo/English |

| Eben | Ayanfe Baba | Yoruba English |

| Dunsin Oyekan | Imole De | Yoruba/English |

| Chigozie Wisdom | E se gan ni | Pidgin/Yoruba/Igbo/Ibibio |

| Kefee | Branama | Isoko/English |

| Infiniti | Olori Okko | Yoruba/English |

| Jimmy D Psalmist | Covenant keeping God | Yoruba/Engliish |

Musical Examples

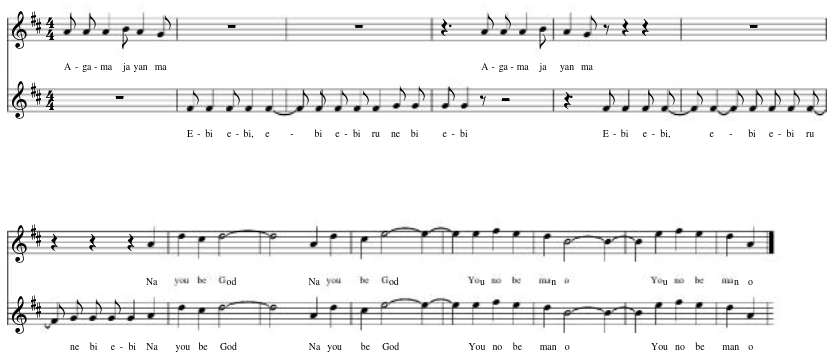

This is a musical extract from Nathaniel Bassey Onise Iyanu showing code mixing. The texts in the first two bars are in Yoruba while the last two are in English

This is a musical extract from Tim Godfrey Na You Be God showing code mixing. The texts in the first eight bars are in Igbo while the last seven are in English

Listed in the table below (Table 4) are names of some notable Nigeria gospel artists who sang 90% of their songs in their local dialectical tongue with one or two numbers within an album in either other Nigerian languages or in the nation’s official language i.e. English between the 1970s to late 1990s.

| S/N | Names of Artiste/Groups |

|---|---|

| 1 | Bola Are |

| 2 | The voice of the cross brothers Lazarus and Emmanuel |

| 3 | Niyi Adedokun |

| 4 | Cherubim and Seraphim Ayo Ni’O choir, Apapa road Lagos |

| 4 | Good women choir, C.A.C Ibadan. |

| 5 | Pernam Percy Paul |

| 6 | ECWA church choir, Takete |

| 7 | Remi Olabanji (CCC) |

| 8 | Joseph Adebayo Adelakun (Ayewa international) |

| 9 | Patty Obasi |

| 10 | Ojo Ade |

| 11 | Funmi Aragbaye |

| 12 | Chika Okpara |

| 13 | Luke Ezeji |

Conclusion

Based on the result of the analysis of the findings of this paper, it was discovered that multi-lingual songs are more appreciated than mono-lingual songs. The influence which multilingualism has over mono-lingual cannot be downplayed in terms of human development physically and socially. The results also reveal that the multi-lingual artist has more reach than the mono-lingual artists. It brought about a high level of popularity of the individual artist or singing groups and their songs. It serves as a medium of uniting the different ethnic groups through the multi-lingual songs and having a sense of belonging within and outside their domain or state of origin. Finally, this paper concludes that multi-lingual songs are more acceptable by the audience. These have brought about accelerated growth of the gospel music industry. Hence, gospel artists should create more multi-linguals.

References

- Abdulkhaleq, A. 2014. The Phenomenon of Code–Switching and Code Mixing as Practiced Among Faculty Members in Saudi University. Language Phenomena in Urban Society Conference, Surabaya, Indonesia.

- Alemede, E. O. 2013. "The contribution of cherubim and seraphim church Ayo ni o, Apapa road, Lagos to the development of gospel music in Nigeria." Unpublished Master’s thesis, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

- Babalola, E. T and R. Taiwo. 2009. "Code-switching in contemporary Nigerian Hip-Hop music." Itupale Online Journal of African Studies Vol. 1, 2009.

- Canfield 1980. "Navaho-English Code Mixing." Anthropological linguistics (22): 218 – 221.

- Cambridge English 2017. The impact of multilingualism on global education and language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge English Perspectives, Pp. 6 -9.

- Daramola, Y. 2008. Christian Music as a Discipline: A Religious Appraisal of Christian Music in Nigeria today. pctn.org.

- Elger, D. 2007. "Theory of Performance." In Faculty guidebook: A comprehensive tool for improving Faculty performance (4th ed.), edited by S.W. Beyerlein, C. Holmes, & D. K. Apple, 19-22. Lisle, IL: Pacific Crest.

- Graves, T. D. 1967. "Psychological Acculturation in a Tri-ethnic Community." Southwestern Journal of Anthropology (23): 337-350.

- Ingrid, P. 2016. "Monolingual ways of seeing multilingualism." Journal of Multicultural Discourses 11 (1): 25-33.

- Kuponiyi, A. O. 2013. "Code Switching in Contemporary Nigerian Hip Hop." Published Thesis dissertation Submitted to the University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana.

- Liadi, O. F. and A. O. Omobowale. 2011. "Music Multilingualism and Hip Hop Consumption Among Youth in Nigeria." International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology vol. 3 (12): 469-477.

- Mithen, S. 2006. The Singing Neanderthals the origins of Music, language, Mind, and Body. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Moyo, T. 1996. "Code-switching among competent bilinguals: a case of linguistic, cultural and group identity." Southern African Journal of Language Studies 4 (1): 20-31.

- Okal, B.O. 2014. "Benefits of Multilingualism in Education." Universal Journal of Educational Research 2(3): 223- 229. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2014.020304

- Oyewo, Y. 2000. "Human Communication." In An introduction in Studies in English, edited by O. Babajide Adeyemi, 149-167. Ibadan: Bookraft

- Prentice, D. A., and T. Dale, T., eds. 2001. Cultural divides: understanding and overcoming group conflict. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. P.230. ISBN 0871546892

- Quarcoo, M., Evershed, E. Amuzu, and A. Owusu. 2014. "Code Switching as a Means and a Message in Hiplife Music in Ghana." Contemporary Journal of African Studies. Vol. 2. 1-32.

- Rust, C. 2002. Purposes and principles of assessment. Learning and Teaching Briefing Papers Series, 3–5. Retrieved from ltac.emu.edu.tr.

- Seth, A. O. 2015. Monolingualism & Multilingualism. Sociolinguistics notes. Downloaded from acasearch.

- Sridhar, Kamal. 1996. "Societal Multilingualism" In Sociolinguistics and Language Teaching, edited by Sandra Mckay, and Nancy Hornberger, 47-70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1996.

- Stein-Smith K. 2017. "The Multilingual Advantage: Foreign Language as a Social Skill in Globalized World." International Journal of Humanities and Social Science vol. 7(3): 48–56.

- Sumarsih, M., S. Bahri, and D. Sanjaya. 2014. "Code switching and code mixing in Indonesia: Study in sociolinguistics." English Language and Literature Studies 4(1): 77-92.

- Wani, Sajad Hussain and Adil Kak. 2007. "Strategies of Neutrality and Code Mixing Grammar." In Recent Studies in Nepalese Linguistics, edited by Aadil Amin Kak In Novel K Rai, Yogendra P Yadava, Bhim N Regmi and Balaram Prasain, 467-86. Proceedings of the 12th Himalayan Languages Symposium and 27th Annual Conference of Linguistic Society of Nepal. ISSN: 0259-1006.