#3 The Words and Music of Dichterliebe

UDC: 78.071.1 Шуман Р.

78.01

COBISS.SR-ID 33178633

_________________

Received: Dec 15, 2020

Reviewed: Jan 24, 2021

Accepted: Feb 03, 2021

#3 The Words and Music of Dichterliebe

Citation: Shao, Xin. 2021. "The Words And Music of Dichterliebe." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 6:3

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to help singer to get more ideas for interpreting Robert Schumann’s work Dichterliebe (1840) through analyzing its relationship between words and music. The article also simply stating Schumman’s love story and his setting music of Heinrich Heine since this piece could be seen as a music resume of Schumann’s life. Otherwise, Word painting is a common composition tool for his work. Accordingly, the article analysis and shows the corresponding between the word meaning and piano part in this song cycle.

Dichterliebe, Robert Schumann, Heinrich Heine, word and music, song cycle, word painting

Introduction

What happens when an emotional and intelligent composer becomes interested in beautiful and sentimental poetry? Songs and song cycles, of course. Many singers consider Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe (1840) to be their favorite song cycle. It includes sixteen songs to poetry by Heinrich Heine. Schumann composed the song cycle in just over a week. Its exquisite blend of words and music has caused it to become among the most widely known German Romantic song cycles. What makes this work so exceptional? In this essay, I discuss Schumann and Heine, and then investigate the relationship between the piano and the voice in Dichterliebe. As one of the leading composers of the Romantic era, Robert Schumann (1810-49) devoted his entire life to music. His songs have tremendous artistic appeal in part because he did not separate the essential essence of a poem, its words, from the music, which he used to express deep inner feelings where words would fail. His exceptional talent of setting words to music came from his love of reading books and old literature when he was a child. Schumann is generally considered an expert in short character pieces instead of larger works. Among his most popular collections of short pieces or cycles are Carnival (1834-1835) and Kreisleriana (1838) for solo piano and Liederkreis (1840) and Dichterliebe for solo voice and piano.

The Words and Music of Dichterliebe

Heinrich Heine (1797-56) was a significant figure in German literature. Humor and irony are central to his writing style, and his poems concern the tragic experience of love and delicate emotions. He experienced the pain of love firsthand, and this became evident in his poetry. Heine fell in love with his cousin Amalie Heine when he was 18. However, Amalie’s father forced her to marry the manor owner’s son. Then, Heine transferred his love to Amalie’s sister, but she directly refused him. Undoubtedly, these experiences of love created huge shadows in his heart and mentality. He was at first full of passion about love: then he started to suspect that Amalie never loved him and began to recognize love as an unforgivable betrayal. Heine wrote a collection of poems titled Lyrisches Intermezzo (Lyrical Intermezzo) in 1822-23; the poems came two years before he was crossed in love. The 65 poems in the collection may presage his tragic love experience. They were published as part of Buch der Lieder in 1827, two years after his romantic tragedy.

Schumann set poetry from nearly every poet of his generation, including Heine. Over his lifetime, he set 38 of Heine’s poems to music. Schumann met Heine in Munich in 1828, when Schumann was 18 years old (Hallmark 1979, 7), and he was attracted to several of Heine’s personal characteristics. They came from similar social backgrounds, and both hated the corruption and hypocrisy in society. Schumann related to Heine’s melancholic temperament, which was similar to his own. Heine was experienced at the suffering of love, which resonated with Schumann.

Schumann discovered Heine’s Lyrisches Intermezzo at the time when he was being forced to separate from Clara, who herself was a renowned pianist and composer, and she inspired Schumann to focus on writing love songs. This formed a significant connection between the two men. Then, Schumann began setting Heine’s poems to music in 1840 with Liederkreis, op. 24, and Dichterliebe, op. 48, the year in which Heine’s Buch der Lieder had become one of the most popular poetic anthologies of the time (Perrey 2007, 126).

Dichterliebe, op. 48 is a song cycle based on Heine’s collection of poems Lyrisches Intermezzo. The poems describe a woeful love-struck knight who sits in his home all day. His fairy bride visits him at night, and he dances with her until the next day arrives and she returns him to his room.

Heine’s poetry emphasizes a man’s love for a woman. Heine rarely writes about maidens and young girls’ love for a man; instead, he often relates his own experiences of love from real life. For instance, in Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen (no. 40 in Lyrisches Intermezzo, no. 11 in Dichterliebe) he describes an old story of a youth’s love:

A youth loved a maiden who chose another: the other loved another girl, and married her. The maiden married, out of spite, the first and best man that she met with: the youth was sickened at it. It's the old story, and it's always new: and the one, who is turned aside, had his heart broken in two. (Hallmark, op.cit., 22)

The response of Schumann when he read this poem was delicate and sensitive. He knew about women’s thoughts and he sympathized with them. Clara’s father angrily prevented Clara and him from being together, and the poem raised Schumann’s interest and gave him the inspiration to set the texts (Miller, 1999, 98).

The poems and music of Dichterliebe

As a composer, Schumann equalized the roles of the piano and the voice in his songs. The piano is not just accompaniment; its functions in Lieder include preludes, interludes, and postludes. It also completes vocal lines and provides tonal closure when the vocal part does not end on the tonic. This relationship is evident in Dichterliebe.

Schumann chose 20 poems from Heine’s collection that included fine rhythmic momentum and readability. However, only 16 songs were published in the original set. After Schumann selected poems from Lyrisches Intermezzo, he started to conceive a melodic setting. His first written idea of a song is not a fragmentary idea but rather a complete or nearly complete voice part, fully texted. (Hallmark op.cit., 22)

He envisioned Dichterliebe as connected character pieces. Most songs are connected by unfinished endings or half cadences. Therefore, some pieces in Dichterliebe are not good for singing individually.

| Dichterliebe Lyrisches | Intermezzo | |

|---|---|---|

| Im wunderschönen Monat Mai | No.1 | No.1 |

| Aus meinen Tränen sprießen | No 2 | No.2 |

| Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube, die Sonne | No.3 | No.3 |

| Wenn ich in deine Augen she | No.4 | No.4 |

| Ich will meine Seele tauchen | No.5 | No.7 |

| Im Rhein, im schönen Strome | No.6 | No.11 |

| Ich grolle nicht, und wenn das Herz auch bricht | No.7 | No.18 |

| Und wüßten's die Blumen, die kleinen | No.8 | No.22 |

| Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen | No.9 | No.20 |

| Hör ich das Liedchen klingen | No.10 | No.40 |

| Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen | No.11 | No.39 |

| Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen | No.12 | No.45 |

| Ich hab im Traum geweinet | No.13 | No.55 |

| Allnächtlich im Traume seh' ich dich | No.14 | No.56 |

| Aus alten Märchen winkt es | No.15 | No.43 |

| Die alten, bösen Lieder | No.16 | No.65 |

The storyline of the song cycle is as same as that of Schumann’s and Heine’s love experiences. Nos.1-6 describe a poet’s love for a girl. Nos. 7-14 concern the poet’s suffering after he lost the girl. Nos. 15-16 tell of the poet’s decision to bury this love. Most of the songs in Dichterliebe are in strophic form, like the poems themselves. Schumann created a variety of settings in the cycle, depending on the nature of the poem. For example, he used a declamatory style in “Die alten, bösen Lieder,” since the text was very serious sounding like the singer was making a vow. Likewise, in “Aus meinen Tränen sprießen,” he created a very simple melody and simple piano part in order to express the objective nature of the poem. (See Example 1.)

Example 1. Schumann, “Aus mienen Tränen sprießen,” mm. 1-4.

English translation: Many flowers spring up from my tears, and a nightingale choir from my sighs: If you love me, I'll pick them all for you, and the nightingale will sing at your window. (Moore 1981,2) Metaphor is an important tool for a poet, including Heine. An image of a woman serves him as his poetic canvas, appearing as Virgin, Madonna, Maiden, Sphinx, or Beast; because, as Beate Julia Perrey (2002) asserts, this image functions as a poetic mirror of Heine’s critique of his time, it becomes the catalyst for his reaction. For instance, Heine described his lover as a holy virgin surrounded by angels in his Lyrisches Intermezzo no. 11.

Dichterlibe analysis

The author divided Dichterlibe into parts based on the protagonist’s emotional changes:

- The first seven songs exhibit the story of the poet from falling in love to failing out of love in the protagonist’s memory. They show a young man who changes his inner feeling from happiness to extreme pain and the music also changes from gentle lyricism to high drama. No. 7, “Ich grolle nicht” is the climax of the entire song cycle. The story notably changes in this song.

- The second part starts from the song eight. The protagonist’s emotion turns to negative. He has full heart of negative emotions. For example, the man feels inner pain while thinking about his love experience, which can be traced from the eighth song “Und wüßten's die Blumen, die kleinen” to the last song “Die alten, bösen Lieder”. The man is being gradually pulled by his sad love to grave and death.

The First Seven Songs

No. 1 “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” (The Beautiful Month of May)

In this song, the scene was set in the past, a month of beautiful May. Everything has energy as well as love. Schumann’s setting of this opening poem establishes a romantic and soft atmosphere to capture the love coming from the young man. This time was the first time that the protagonist confesses to his lover. The song is marked “Langsam, zart,” which means slow and sweet, and the strophic form of the song unfolds a scene of spring blossom and the character’s growing desire for love. In the beginning, Schumann moves between F sharp minor and A major to create a sense of ambiguity (see Example 2) that is never resolved. (Ferris 2000, 92)

It seems to be a symbol of spring, a season of exuberance of love as cold temperatures intertwine with warm ones. Then, the first sentence “In the beautiful month of May'' confirms the atmosphere of the lovely music heard thus far. Arpeggios frequently appear in piano parts and the vocal line to tightly connect both parts. However, the piano seems to play a different mood to contrast the vocal part with a delicate dissonance, which probably indicates some hidden troubles of their love (see Example 3). The author’s view is that it is a rather subtle dramatic that was deliberately made by Schumann.

The arpeggios are preparations for the climax in the middle part of the song at the word “aufgegangen” (unfold). When the music arrives at the climax, the singer and the pianist must match on the crescendo. It feels like a confession to one’s lover. The song does not end with a firm cadence but instead on an unsolved dominant seventh chord, which gives the audience the effect of holding the wonderful moment into the next song.

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai has a great balance between voice and piano, which differs from piano by only playing an accompaniment background. Although the piano part seems as if playing a different role with the vocal line, they are perfectly getting together in harmony, which means the protagonist is talking about his love in the beautiful day that is played by piano. Therefore, the first song is a notable example that Schumann enhanced the function of the piano as important as the role of the voice.

Example 2. Schumann, “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,” mm. 1-6.

Example 3. Schumann “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,” mm. 8-12.

No. 2 “Aus meinen Tränen sprießen” (Many flowers spring up from my tears)

While this is a sorrowful song it is otherwise a sweet one: the protagonist is unsure about his love, but he feels happiness about the preparation of the love. This song continues the sweet mood from the last song, but the entire song is in a little sorrowful emotion as well, which may contribute to the ambiguity of tonality. In the beginning, the piece starts with A major, but then the tonality has a tendency to F# minor. Therefore, the ending of the song does not have a solid cadence. (see Example 4) “Aus meine Tränen” presents a different kind of unsatisfactory cadence, in which the voice constantly ends on a half-cadence that the pianist must resolve. It is as if the pianist mocks the singer/speaker with a disparaging affirmation. (Finson 2007, 63).

Example 4. Schumann “Aus meinen Tränen sprießen” mm.14-18.

No. 3 “Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube, die Sonne” (I used to love the rose, lily, dove and sun)

The song starts with barely a break, which is a great contrast and surprise in comparison with the previous two. This poem exhibits more constancy of pattern than any other poem in Lyrisches Intermezzo through the alternation of two unstressed syllables with two stressed syllables. It is realized musically with in two-measure phrases that seem crowded and flow breathlessly from one to another (Hallmark op.cit.).

The poem expresses the exuberance of love, so it should not become an exhibition of bombastic diction or airflow and subglottic pressure. Schumann sets a vigorous accompaniment for the poem. He uses a combination of sixteenth-notes and rests as the main motivic module with the rose, the lily, the dove and sun to represent the exciting emotions.

In the second part, Schumann gives the left-hand eighth notes instead of sixteenth notes, when the text comes to the fact that she is the rose, the lily, the dove, and the sun. The second part becomes lyrical because the poem turns to love. Also, Schumann adds two “ritardandos” to soften the pace at the words “sie selber, aller Libe Wone” (she herself, the well of all love) and “ist Rose unLilieun Taube und Sonne” (is rose, lily, dove and sun). This creates a more reflective mood.

No. 4 “Wenn ich in deine Augen seh” (When I look in your eyes all my pain and woe fades)

The fourth song contrasts enormously in the mood with the previous one. The starting tempo is “Langsam” and the dynamic is piano. A long silence before the introductory chord of the fourth song should exist to demonstrate the difference.

�This song is an excellent example of Schumann’s extremely sensitive text setting. Schumann sets the text to a rhythmic pattern (See Example 5) according to word stress. The stress is always on the second-to-last word of each sentence. The rhythmic pattern is repeated in both the vocal and piano lines, and this is also a sort of connection between them. The melody of the song is very gentle, and the dynamic does not change much. Therefore, the main idea of the music is to emphasize the meaning of the text:

When I look into your eyes pain and sorrow vanish; when I kiss your lips I am restored. When I lay my head on your breast heavenly joy fills my being, but when you say ‘I love you’ I cannot but weep bitterly. (Moore op.cit., 5)

Example 5. Schumann, “Wenn ich in deine Augen seh,” m.12.

According to the text, the entire poem is in a comfortable mood except at the end of the song, “Ich liebe dich! So muss ich weine bitterlich.” Schumann adds a “ritardando” to emphasize the words “I love you” and adds a crescendo in the last sentence to the word “bitterlich,” which has a stress mark to evoke pain from the deep heart of the protagonist.

No. 6 “Im rhein, im heiligen strome.” (In the Rhine, in the sacred stream)

The song describes the holy cathedral of Cologne on the Rhine River. It relies heavily on the nationalistic imagery of the Cologne Cathedral (begun in 1248 but left unfinished until the 1840s). (Finson op. cit., 64)

The portrayal of Virgin Mary in the Cathedral provokes the protagonist’s recall about his beloved. The bass line in the piano evokes the cathedral’s organ, and the right hand suggests the rolling water of the Rhine. The pattern of the piano line is constant till the end. (See Example 6.) When the poem depicts the holy virgin, “Flowers and angels hover round our lady: her eyes, lips and cheeks are just like my darling’s,” (Moore op. Cit., 7) the left hand of the piano part turns to steady octaves and the right hand maintains the previous rhythm, but the chords are not as solemn and serious as in the first part. The vocal color should be tender and light, and it must be contrasted with the prior strong and mighty feeling.

Example 6. Schumann, “Im Rhein, im schönen Strome,” m. 19.

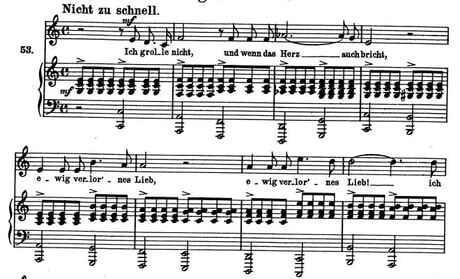

No. 7 “Ich grolle nicht” (I do not chide you)

This poem is the only one in the collection that shows the character’s indignation about the betrayal of love and faithlessness. The song is an obvious transition from falling in love to losing love. Schumann states twice, “Ich grolle nicht, und wenn das Herz auch bricht,” first at the beginning and second at the start of the second section.

Two different emotions are expressed. At the beginning, the piano part starts in a block chord with mezzo forte until the first bass chord appears with forte. The melodic line starts on an upbeat, marked mezzo forte: the word “nicht” is set on the downbeat to be emphasized. This placement reflects the protagonist’s inner conflict about his lover. The second section starts with forte in both parts. It represents the protagonist’s anger based on words in the first section, “Though you shine in a field of diamonds, no ray falls into your heart's darkness.”

The word “nicht” appears six times in this song, which proves its core position. The piano part is mostly repeated block chords, used to evoke a deceptive impression that aims to fit in with texts such as

Long know that a serpent feeds on this heart of yours. I saw, my love, how wretched you are. (Hallmark op. cit.)

Two dramatic crescendos push the music and the poem to a climax at the words “Herzen.” The pulsating rhythm gives a forward feeling while the dotted rhythm in the voice provides a sense of vigor. Meanwhile, with the aim of creating a heavy atmosphere, Schumann put stress marks on most downbeats for the first part of the song. (See Example 7.)

At the end of the song, according to Gerald Moore (op. cit., 8):

Schumann is conservative with high notes in his instructions. Here and there he notates a forte and sometimes a mezzo forte but on the climax a fortissimo, though wanted, is not indicated. Just as surely as the singer will be unwilling to hold back and rightly so on the towering ‘am herzen frisst’. (Moore op. Cit., 9)

So, singers who add the pitch “A” instead of the written “D” at this point help the singing become more dramatic and push the music to the climax more easily (see Example 8). The final word, “nicht,” is on a low pitch (C); most singers will sing very lightly on that pitch because they need to create contrast with the emotional climax. The pianist must maintain the loud dynamic for all three final chords.

Example 7. Schumann, “Ich grolle nicht,” mm. 1-8.

Example 8. Schumann, “Ich grolle nicht,” mm. 26-28.

Translation:

I will not complain though my heart is breaking. Love lost forever! Though you glitter with diamonds I have long known there is no answering ray of light in the blackness of your heart; long known that a serpent feeds on this heart of yours. I saw, my love, how wretched you are. (Moore 1981, 8)

��“Ich grolle nicht” comes in the middle of Dichterliebe. According to the text of the poem, perhaps, “I do not chide you” is what Heine wants to say to his old lover Amalie. The single high A illustrates that the song is the emotional peak of this song cycle.

The Post Eight Songs

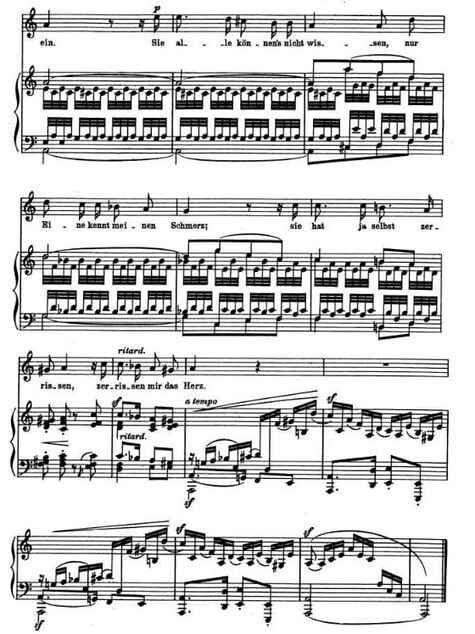

No. 8 “Und wüßten's die Blumen, die kleinen” (Did the wee flowers know that sadness)

This song in No. 8 in Dichterliebe, which is in a different order than Heine’s Buchder Lieder (No. 9). And this also is the first one Schumann changes the order from the original poetry. This song is in a sad mood, the protagonist feels pain when he is thinking about his lover. He realized that nature is the only one that knows his suffering and his pain, and it can make him comfortable.

In the music, this is a contrasted song than the last song; the last song is full of anger and fury, but this song turns into light and swift running tempo. The rapid change expresses the protagonist’s inner contradiction between fury and sadness.

The time is moderato (moderately fast) 2/4. Schumann uses A minor to start this piece, the piano part plays thirty-second running notes that repeat the melody pattern three times about the text “the flower,” “the nightingales” and the “stars” until the text “Die alle können's nicht wissen” (all of them cannot know it) in measure 25 (see example 9). The piano part suddenly appears descending eight notes pattern from measure 26 to measure 28. Later, the piano part stopped - the piano dramatically stopped the vocal line by two eighth notes in measure 30 to fit the word “Zerrissen”, which means “torn”. Then, the vocal line repeats the word “Zerrissen” to finish the last sentence “torn up my heart with a “ritard” tempo. At this time, the piano is back to the original tempo with completely different mood and melody finished this song.

From the analysis, Schumann uses great text painting music skill to match the text especially the dramatic silence in measure 30.

Example 9. Schumann “Und wüßten's die Blumen, die kleinen” mm.24-32.

No. 9 “Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen” (There is a fluting and fiddling)

This is a song, which describes the wedding day between the lover and another man. The music is playing the musical background of a wedding party; the right hand is playing sixteenth notes, which sounds like a crowded and busy scene, the left-hand keeps playing a waltz rhythmic pattern (see Example 10), which represents the dance music. The poem has two verses, the first verse is from the beginning to measure 31 and the second verse is from measure 38 to the end. They are divided by the piano interlude, which is the same as the interlude at the beginning. The music between the first and second verse is the same.

Example 10. Schumann “Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen”. mm. 4-5.

The scene of the wedding party is from the beginning to measure 49. After that, the protagonist becomes despairing on the word “schluchzen” and “stöhnen”. However, the dynamic of the piano part is as always that seems no one cares about the protagonist. Finally, the piano is getting energetic after the vocal line has finished.

No.10 “Hör' ich das Liedchen klingen” (If I hear that little song)

As the contrasting piece, this song has much slower tempo than the preceding one. The simple melody and harmonic progression are leading a confessional mood. The protagonist recalls his beloved’s song that triggers his sadness. The accompaniment is playing descending broken chords throughout the piece. Both the vocal line and piano part are in a depressed atmosphere.

Harmonically, the measure 9-10 shows a non-harmonic progression or harmonic interruption, The tonality from B natural modulated to C minor with a B diminished chord from measures nine to ten (see Example 11). Then, a Neapolitan sixth chord appears in the measure ten in C minor. That transition corresponds to the text “so will mir die Brust zerspringen” (my heart wants to break).

The piano part plays a significant role after the vocal line has finished. From measures 20 to 23, the piano part continues the mood of the sadness. The mood changes after measure 24, the notes getting intensive that the outer line moves to the center, while Schumann also added a note to replace the eighth rest that enriched the harmonic. Finally, the music ends with descending sixteenth notes with the G minor.

Example 11. Schumann “Hör' ich das Liedchen klingen,” mm.9-10.

No. 11 “Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen” (A young man loves a girl)

The song is talking about a story of a man’s unrequited love to a girl. Ironically, such a sorrowful story has a stirring and energetic musical accompaniment. It may reflect the protagonist’s self-contemptuous inner feeling and provoke his memory of the terrible experience of his love.

The rhythmic pattern of the left hand is constantly repeated in the piece. The pieces starts with an upbeat, the rhythm starts to circulation from ♪ ♩ ♪ to ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ (see Example 12). At the middle of the song, the balance is broken from measures 19 to 22. That might represent the sensitive motion invoked by this specific story part. Then the music back the same as the beginning, till the realized the inner pain, a D diminished the seventh chord matches the word “bricht” at measure 30 with ritardando. Then the music goes back to a tempo to continue the memory. The piece ended at the last two repeated tonic chords, which implies this memory has been over.

Example 12. “Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen,” mm 1-4.

No.12 “Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen” (On a shining summer morning)

The song has a beautiful long legato vocal line, and the piano accompaniment is lyric and steady. The tempo is Ziemlich Langsam (rather slowly), which recapped the mood from the first piece. The text mentioned again the beautiful weather, flowers.

This song is like a short recapitulation. In the beginning, Schumann uses arpeggios with dissonance chords to create a beautiful but abnormal mood. The first chord starts with B flat major, then a Ger. 6 Chord followed by the next chord (see Example 13). This music sounds frightening to the author. Then it is back to consonant chord and tonality. Then the Ger.6 chord appears at measure 6 again. Two diminished seventh chords appear at measure nine. Later, the Ger. Chord shows at the major 11 one more time.

The author believes that Schumann uses accompaniment to reflect the protagonist’s inner feeling, and he uses vocal ling to be the objective narrative since the vocal line does not have much dynamic change and emotional wave through the entire song. Therefore, the piano part takes a primary position in this piece.

Example 13. Schumann, “Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen” mm 1-2.

No.13 “Ich hab’s im Traum geweinet” (I have in my dreams wept)

The song is in a funerary mood, which established a slow tempo. The protagonist dreams about his beloved lay in the grave, which induced his grieved emotion. The only thing he can do is weeping his tears.

Most of the vocal line is in slow reciting style without accompaniment. The piano part has a rhythmic pattern as the background (see Example 14). The musical form seems like mourning during a funeral ceremony. In particular, it shows in the dynamic, the strongest dynamic mark has not exceeded the piano. The protagonist repeats the sentence “Ich hab' im Traum geweinet” (I have in my dreams wept) three times. The last time is the weakest one to contrast the dynamic gradually revived on the text “Ich wachte auf, undnochimmer” (I dreamed you still love me). The dynamic is getting active, which marks “crescendo molto” that reflects the reality; his beloved has left him forever that he finally realized and that was a final disillusionment.

Example 14. Schumann “Ich hab’s im Traum geweinet”. mm. 1-4.

No. 14 “Allnächtlich im Traume seh' ich dich” (Every night in my dreams I see you)

This piece is still in the protagonist’s dream as well as the proceeding one. In this dream, the protagonist seems to have hope with his beloved. The beautiful girl talks the sweet word and gives a bouquet to him. When he suddenly wakes up, everything is an illusion. The piece sounds beautiful, it reflects, however, a dramatic contrast between a wonderful dream and a cruel reality.

The vocal line is intermittent (see Example 15), which is not as legato as other lyric pieces. The vocal lines frequently interrupted by the eight-rests. That probably reflects the protagonist's inner feeling, which hardly believes what he saw and what he heard. In the piano part, the right-hand plays intervals, which seems broken. However, Schumann uses left- hand to link each measure by the last eighth note of the measure to the next measure. Meanwhile, he uses the perfect fifth chord to maintain the harmonic mood of the entire piece.

Example 15. Schumann, “Allnächtlich im Traume seh' ich dich,” mm. 6-8.

No 15. “Aus alten Märchen Winkt es” (From old fairy-tales it beckons)

This song is the longest one in the cycle, which indicates the poet’s lengthy expectation of beautiful world without any of suffering. The song is in E major and the time signature is in 6/8 with tempo marked Lebendig meaning lively. In general, the basic rhythmic pattern both in piano part and in vocal part through the entire song is constantly of one quarter-note (or one eighth- note and an eighth-note rest) and one eighth-note, which reflects a forward and passion motion (see Example 16 and Example 17a).

Example 16. Schumann, “Aus altn Marchen Winkt es” mm. 6-9.

Example 17a. Schumann, “Aus altn Marchen Winkt es” mm. 18-21.

According to the meaning of lyrics, it can be divided into three parts.

- The first part is from the beginning to measure 64, which expresses the wonders of the extraordinary magic land.

- The middle part is from measure 69 to 83 and marked under Mit innigster Empfindung. Meaning with most inward feelings. The musical pace becomes relatively slower due to the change of rhythmic pattern that contains three plus three beat-patterns or five plus one beat-pattern in one measure (see Example 17b). It also refers to a compositional technique of augmentation by increasing the note values in this climax section. This part describes that the poet hopes all the anguish is taken away in this fairyland.

- The last part is from measure 92 to the ending, which presents the poet's regret of this dream having to melt away like mere froth along with the raising of the morning sun.

Example 17b. Schumann, “Aus altn Marchen Winkt es” mm. 69-75.

Generally speaking, the piano accompanying part supports the vocal line with a sense of propulsion and mostly provides pitch support by the top line of the right hand. The general color of this piece is light and dreamy.

The ending of this song is marked with adagio and ends quite soft, which refers to the sense of drifting away. The fermata after the ending of the vocal part is also a magic moment that surprises people by wondering what is coming next. Then the part of the main theme comes back which reinforces and impresses the audiences by the power of repeating.

No. 16 “Die alten, bösen Lieder” (The old, angry songs)

The song is the last one of this cycle. The introduction of the piano part only has three measures, but it implies the conclusion of the cycle according to these I to V to I rich chords with fanfare feeling. It also sets up the motive for the vocal line as the first phrase of the vocal line repeats it with a slight difference.

The piano accompaniment reflects not only the entire mood but also the lyrics of this cycle. For instance, the meaning of the text is that the coffin shall sink down into the sea carried by the giants in the section from measure 36 to 39 (Example 18). The piano part perfectly describes it by using big rich chords per beat to imitate the steps of the giants. The first and the third beats of each measure have the roots of the current chords played by only the left hand. However, the beat two and beat four are especially fuller due to the full chords playing by both hands together along with marked accent. It implies the uneven steps of the giants because they carry the heavy coffin, so it is a type of text painting.

Example 18. Schumann, “Die alten, bösen Lieder,” mm. 39-39.

This song is marked under Ziemlich Langsam, which means rather slowly. Until the last phrase of the vocal line, it changes to Adagio since the coffin was sunk along with his love and pain. The postlude of the piano is relatively long from the measure 53 to 67 and it switches to its end under the tempo marking Andante espressivo.

The time signature also changes from 4/4 to 4/6. At the last three measures, the A-flat major- minor seventh chord has been repeated three times, then the seventh of that chord is suspended two beats and resolves to the third of the D-flat major chord, which is the last chord of this song.

In addition, the long postlude represents the significant role of the piano in this cycle by giving the extraordinary ending, which contrasts in tempo, time signature, key signature, mode, and styles.

Conclusion

To conclude, I will recommend some recordings on which the performers masterfully interpret this work. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is a high baritone, who focused on singing art songs for years. He can change his timbre to suit the music as needed. The tenor, Fritz Wunderlich has a beautiful tone and fine sentiments, which he uses to appropriately handle the relationship between text and music in his recording of Dichterliebe. Matthias Goerne is a current German Baritone with a powerful voice and very dramatic interpretive abilities. In their recordings, the three singers are very concerned about the relationship between the voice and the piano and treat the piano part as the part of their singing. This is the most important thing that we should learn from their performances.

References

- Ferris, David. 2000. “Poem and Song.” In Schumann’s Eichendorff, Liederkreis and the Genreof the Romantic Cycle, 92. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Finson, Jon W. 2007. “Irony and the Heine Cycles.” In Robert Schumann: The Book of Songs, 61-70. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hallmark, Rufus E. 1979. The Genesis of Schumann’s “Dichterliebe.” Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms International.

- Miller, Richard. 1999. “Dichterliebe (Heine). Opus 48.” In Singing Schumann. 96-114. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Moore, Gerald. 1981. “Dichterliebe.” In The Songs and Cycles of Schumann, 1-23. London: HamishHamilton.

- Perrey, Beate Julia. 2002. Schumann’s “Dichterliebe” and Early Romantic Poetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Discography

- Schumann, Robert. Schumann-Dichterliebe|12 Kerner-lieder. Fischer-Dieskau with Jorg Demus. Gunther Weissenborn. Universal Music Company 463 500-2. 1965. CD.

- Schumann, Robert. Fritz Wunderlich in concert. Fritz Wunderlich. Myto Records 932.78. 1966. CD.

- Schumann, Robert. Dichterliebe and Liederkreis. Matthias Goerne, Vladimir Ashkenazy. Decca 289 458 265-2. 1988. CD.