#4 Exploring Differences In Piano Teaching Between The United States And China

UDC: 37.091.3::786.2(73)

37.091.3::786.2(510)

COBISS.SR-ID 33207561

_________________

Received: Oct 05, 2020

Reviewed: Dec 24, 2020

Accepted: Jan 15, 2021

#4 Exploring Differences In Piano Teaching Between The United States And China

Citation: Liu, Xueli. 2021. "Exploring Differences In Piano Teaching Between The United States and China." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 6:4

Acknowledgments: This paper was the part of Doctoral Treatise at the University of Missouri Kansas City. The treatise was defended on September 9th, 2018. The author expresses her gratitude to the professors and supervisory committee Robert Weirich (professor directing treatise), Chen Yi (Committee Chair), and Zhou Long (Committee Member).

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to explore differences in piano teaching between the United States and China. This paper examines the differences through both broad and narrow perspectives. It first examines the history of the development of general music education in the United States and China respectively, providing a background to the differences in piano education. Then it discusses the dissimilarities in piano study from three outlooks: the parental influence, the students’ motivation, and how the study of music can improve one’s overall capacities. Additionally, I will compare the prevalent piano teaching theories of both countries, including teaching styles, materials, and syllabi. From the narrow side, I will contrast specific pedagogical diversities in private piano teaching between the USA and China. Finally, class piano and studio-class are examined to demonstrate the distinction between methods in the USA and China. I have analyzed the inconsistencies in piano teaching between these two countries. I hope that piano educators can efficiently identify the best teaching strategies by recognizing the essential ones and improving the inferior ones.

music education, differences, USA and China, western music pedagogical approaches

Introduction

Historical Summary of the Development of Music Education

a. In the United States

Musical education in the United States has a long history. Back in the 18th century, music training had already started to develop and flourish in the United States. It first appeared in church, teaching basic information about reading music and singing. Later music became a curricular subject in schools. Music training improved quickly and by the 20th century throughout the country, many public schools had music programs. Also, music education expanded to many levels, such as for preschool, elementary school, and high school. In higher education, Oberlin Conservatory, became the first college to offer the four-year Bachelor of Music Education degree in the United States. (Stanford 2018)

Furthermore, training in music became an increasingly significant component of human culture. Music education gradually became an equivalent field of study to such academic majors as economics and physics. It was not uncommon for students of all ages to pursue music study. Children learned singing or to play instruments by joining diverse types of ensemble activities from primary to secondary education, such as choir, school orchestra, and marching band. Moreover, music classes were offered as general music education for appreciating music. Students might have some opportunities to perform in music classes or activities. Hence, music is often important while they study in school.

Professional music education at advanced levels led to bachelor, master, and doctoral degrees. The Bachelor of Music degree emphasizes performance as a major on a specific instrument or singing; the Bachelor of Music Education emphasizes teaching music. Professional music curricula generally include courses in theory, history, literature, pedagogy, and so on. Students get academic credits for completing these classes. They focus not only on learning to identify the different musical styles, but also on music teaching methods. Piano education was historically popular and vital, because the piano played a fundamental role in understanding music theory, and because the piano could substitute for the full orchestra. The keyboard skills class is required for all non-piano major students in their first year at most universities.

Furthermore, physical facilities in American schools are more advanced than in many other countries. Take piano as an example. American schools mostly offer grand pianos for piano major students to use for individual practice. In China, grand pianos usually are offered only in teachers’ studios due to the shortage of resources and spaces.

In addition, many schools provide only Steinway pianos in the practice rooms for students in America. Almost every classroom has a piano and a computer with a projector and screen.

b. In China

Music education in other countries tends to become more common when their economics improve. This is true of South Korea, Japan, and China. However, the musical education in these countries is very different due to diverse politics and cultural backgrounds. China is an excellent example to fit this argument.

The development of education in China is complex. With over 1.3 billion people, the government faces a primary problem providing both food and education. As a consequence, improving agriculture and education are the most important tasks in China. In the educational area, the nine-year compulsory education system (from elementary school to junior high school) was approved by the Chinese government in the 1950s. (Su 2002, 36-38) Due to the large population, competitive awareness existed everywhere.

Thus, the curricula were very specific and intense to keep students’ academic pressure even in elementary school. Courses consisted of Chinese, mathematics, nature, history, geography, music, drawing, and physical education. Also, those courses will combine with practical activities, such as exercises for body and eyes relaxation, flag-raising ceremony, and marching band. The Chinese education was famous for its rigor, so the study burden was significant for students. There was a large amount of homework for two to four hours every day. At the end of a semester, non-academic classes, like music, drawing, and physical education, were usually usurped by academic review sessions. Music class had a lower position than academic classes at that time.

However, the Chinese government reduced the study burden in the 1990s, specifically for primary and secondary school students. It was thought important to provide reasonable time for students to strengthen various life experiences after school. As a result, literature and the arts have experienced a great increase since then.

c. The Introduction of Western Music to China

The introduction of Western music changed Chinese musical history. Before Western music was introduced to China, its musical world was completely different. The development of Chinese traditional music had an extremely long history and occupied a prominent cultural position. It focused on traditional instruments like the Erhu and Pipa, dances, folk songs, and Chinese operas until the early 19th century.

Although Western music formally arrived in China in 1601, when the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci presented a clavichord to the emperor of Ming dynasty, (Melvin 2018) it did not become familiar until the end of Cultural Revolution in 1976 (Bonadio 2018). In 1979, the famous violinist Isaac Stern was the first American musician to visit China and collaborate with a Chinese symphony orchestra. (Stern 1999, 255-256)

This historical musical collaboration opened a new vista in China. Conservatories in China were founded and expanded rapidly. At present, there are nine main conservatories, along the order of the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, and Sichuan Conservatory of Music. The Shanghai Conservatory of Music was the first music school to teach Western techniques. (Bonadio op.cit.)

In some ways, Western music overtook Chinese traditional music, as can be seen in the ratio of curricula in the educational system at music schools in China. Roughly, almost eighty percent of the curriculum is about Western music, which includes harmony, theory, counterpoint, orchestration, Western musical form, and music history. None of these subjects, however, existed in the traditional Chinese musical system. Composers began to write music that apply Western techniques, such as counterpoint to Chinese melodies. Representative works include the Yellow River Piano Concerto, based on the Yellow River Cantata by composer Xian Xinghai. (Ibid.). Composers like Chen Yi, Zhou Long, and Tan Dun are internationally famous.

Moreover, many people started to learn Western instruments such as piano, violin, cello, and flute, and some traveled and began to absorb influence abroad. The piano became the most popular instrument among other Western instruments. Not only are children interested in piano lessons, but keyboard-skills classes were started in the university in China recently. The famous Chinese pianists include Lang Lang and Yuja Wang.

Historically, Western music was studied earlier in the USA than in China since it was settled by European. However, the study of Western music in China has greatly expanded in the last half century. The ability to read music is now more widespread than in the past. In both America and China people attend concerts like in European countries. Many new concert halls are located in major cities, providing more opportunities to appreciate music. Two beautiful new halls are the Shanghai Opera House and the National Center for the Performing Arts in Beijing.

Three Comparisons of Piano Study between the United States and China

Due to the different cultural backgrounds between America and China, there are a variety of views about piano study. I have taught both Chinese and American students for many years. My teaching experiences and my research lead me to focus on three areas: the influence of parents, how students are motivated, and how music study improves the students’ capacities in other areas.

a. Parental Influence

Parents may contribute to their children’s success in the piano study. As shown by Comeau and colleagues (2012), when parents observe their children’s lesson, the children will practice more, be interested in piano performance and creativity more, and feel more competent at the piano. Also, when parents participate, it likely gives the children a message that the parents truly believe in the value of piano playing and encourage deeper engagement on the part of the children. (Idem, 190-191)

Chinese parents are more likely than American parents to help their children with piano practice and sit in on their children’s piano lessons. There is evidence that Asian parents generally take greater personal responsibility for their children’s education (Ibid.) The study by Stevenson and Lee (1990) comparing Asian and American sixth and seventh grade students found that:

47% of Asian parents, compared to 7% for American parents, were carefully structuring their children’s time so that, even out of school, they would focus on academic related skills through private lessons in music, to their children’s learning process. (Idem 66-67)

Taking my own learning experience as an example; my mother sat in when I started piano lessons. Since I was only four years old, she took notes for me and learned almost everything during the lesson time as well, and then always sat with me to practice for two entire years. Sometimes, she even acted as a “teaching assistant.” From what I know of other Chinese natives, this is a fairly common situation. Most of my Chinese students’ parents choose to sit in on lessons, even though many of them do not know how to play piano. The parents assist their children in every way they can, such as making notes, recording the lesson, or asking questions at the end. Most Chinese children are not as averse to it as American children.

It is important that parents and teachers communicate and cooperate in the interest of the children’s study. Younger children need more parental help than older children during the learning process. The degree to which the student improves is closely related to the frequency with which a parent helps the children with home practice. Consequently, I believe that parental influence matters a great deal to their children’s piano study. Parental efforts may not be efficient as those of the teacher, but the children’s growth can be enhanced through this cooperation between parents and instructor.

b. Student Motivation

My experience suggests that Chinese children are more motivated to play the piano than American children. The motivation starts with the parental influence I discussed above and joins with the student’s innate autonomous motivation.

Generally speaking, Chinese youngsters practice piano more than American youngsters. Both Chinese parents and children strongly believe that musical training requires hard work and effort, regardless of one’s talent. Chinese children practice every day as a daily task practicing longer each day than their American counterparts. This commitment to intensive work usually gives the Chinese children an edge over American children when it comes to the basic technical skills of piano playing.

In my experience, most American children learn and practice piano for their personal pleasure. Instead of thinking of practice as a daily task, they practice because they want to do it for their inner feeling. I call it internal-factors. However, since Asian culture is collectivistic, Chinese children are more likely to be motivated pleasing their parents and teachers. I call it external-factors.

Although they may be more motivated at first to please their teachers and parents, eventually they may find an intrinsically enjoyable feeling in their faithful daily practice. Extrinsic motivation is not necessarily harmful in Asian cultures. As long as the person subjectively distinguishes the external-factors, they can still experience the many benefits of intrinsic-factors or autonomous motivation. (Zhou et al. 2009, 492-493)

c. Music Study as a Means to a Greater End

A key regarding music study concerns the future benefits that come to other areas of life as a result of the music study. Many researchers have explored the benefits of listening to music passively as well as pursuing music actively, as in learning an instrument.

The benefits of music in the classroom and its effects on brain development, academic performance, and practical life skills have been observed through research by Jenny Nam Yoon. She found that “the two hemispheres of the brain are stimulated when music is played and how the corpus callosum, the bridge that connects the two hemispheres, is larger in musician's brains.” (Yoon 2000, 3-5) A 1981 study at Mission Viejo High School concluded that music students had a higher GPA than students who did not participate in music (3.59 vs. 2.91). There have been studies done verifying music as an enrichment activity that causes an increase in self-confidence, discipline, and social cohesion, as well as academic benefits. (Dearing et al. 2004, 446-7)

Although this viewpoint still has objectors, most people believe that music provides children with cognitive and emotional benefits, such as “improving spatial and temporal brain functions, which may help them succeed in other school subjects.” (Slaton 2012, 34) Socially, advocates describe music as something that provokes peace, passion, and reduces stress, which they feel provides multiple benefits to students. (Lewis 2003, 56-7)

Since the Chinese economic reform (1978), the population has gotten richer and achieved a higher standard of living. This allows people to focus on the establishment of a spiritual world. Especially in the late 20th century, a great many families started to let their children learn instruments.

Nowadays, music training has become increasingly common in China, even including prenatal education especially suited for mother and fetus. More and more people are learning music as a hobby, and also consider music as their future career.

Musicians in China have even achieved the status of role models. There is a policy that students can earn extra points for the college entrance examination (similar to the SAT in America) if they pass an additional exam of a special artistic skill, which includes vocal, instruments, dance, drama, calligraphy, and painting. This additional exam exists for high school art specialty students, not art majors. Almost every high school student in China will take the national college entrance examination in order to get into a college or university; this in turn will lead to a better job after they graduate.

Therefore, many students undertake a specialty of art in order to get a chance to earn higher scores for the examination; piano is a fashionable choice among these specialties.

Piano Teaching Theories in the United States and China

a. American-Style Piano Teaching vs. Chinese-Style Piano Teaching

American-style education believes that one can “learn from playing”, which is to say, learning should be fun. Some educational experts think that learning piano should be more like a game than a traditional “imitate the teacher” lesson. American teachers are especially focused on this when working with beginners.

I have observed American teachers make a game of learning to learn music, putting notes or rests on cards to let children choose the correct answer. Or the teacher will give little rewards, like a little red flower decoration, when the student makes one small improvement. This could add to the students’ motivation to some extent.

Personal creativity and independence are much valued in America. As a result, children may be allowed to choose what they want to study. American parents are not likely to force their children to continue if they no longer want piano lessons.

Moreover, American piano teachers love to arouse broader interests in students. They may introduce material beyond the major class, such as information about piano literature, and duo-repertoire class.

In addition, many Western countries provide ensemble courses for young students in piano study to increase the cooperation ability. As a result, Western pianists generally are more experienced with ensemble music than Chinese pianists. American educators believe the goal for teaching is not only to train a soloist but also to become a comprehensive musician who can promote and preserve music.

Chinese parents usually have higher specific goals for their children. The parents will encourage or even force them to keep learning piano when they lose interest. Chinese professional music education rarely offers chamber music or literature courses with private lessons in pre-college.

However, basic technical training is given great attention in order to cultivate the so-called talented students, who can play difficult and technically demanding pieces. The difference in educational approaches between the United States and China can be seen as early as kindergarten. Kuzmich (1995) surveyed and interviewed school music educators in both North America and China. Classes are more student-centered in America, where the focus is on the students’ feeling and enjoyment.

But in China, classes are more teacher-centered; the students are expected to follow the teacher’s instructions. (Ibid., 31-35) Rote learning is typical in the old Chinese-style of learning; a student’s task is to write down or memorize whatever the teacher gives. In the piano lesson in China, imitation is the most important part of the lesson rather than an emphasis on creative activities. Historically, Chinese teachers taught in a serious and strict atmosphere. In old Chinese educational culture, there are many sayings like “Talented students are trained by strict teachers”, and “Beating implies intimacy, scolding implies love.” ( These are old Chinese folk sayings that I have translated here, “严师出高徒” and “打是亲,骂是爱.” )

However, American-style education has had a major influence on Chinese education as culture globalization spreads. Now, more and more Chinese teachers focus on cultivating students’ interest and combine good aspects from both educational styles in piano studying.

b. Piano Teaching Materials For Beginners

In China, piano teachers concentrate on the training of basic technique. During the learning process, students are required to practice a large number of basic technical exercises. The most commonly used materials include: Bayer’s Elementary Method for the Piano, Op. 101, Hanon’s The Virtuoso Pianist in Sixty Exercises, Czerny’s Practical Method for Beginners, Op.599, and Brahms’ Fifty-One Exercises for the Piano. All these books have become indispensable exercises for piano students. Hanon remains part of piano practice for a long time. The scales, arpeggios, and some exercises in the Hanon have also become obligatory parts in the test of levels for amateur players.

Chinese piano teachers believe that a student will inevitably encounter an insurmountable difficulty when he enters the intermediate level and will not be able to move much farther unless the student has a solid technical training from the beginning.

Piano education in the United States is different from other countries. It integrates education methods from around the world because the United States is an immigrant country. Especially during the Second World War, many musicians fled from all parts of the world to the United States. Musicians from other countries brought their own ethnic characteristics and educational methods to the United States. Through long use and development, these methods were gradually codified and became accepted as the so-called American-style education.

In the United States, there are many types of piano teaching materials available for beginners besides Bayer and Hanon. These include Piano Adventures, Bastien Piano Basics, Alfred’s Basic Piano Library Lesson Book, and The Music Tree. Each set is a series, essentially a brand, which usually consists of a main lesson book, theory or activity book, and performance or recital book. Each series proceeds in a coordinated way, but each book has its own characteristics. For example, a theory book will have some exercises like chord progression and improvising, which is lacking in the Chinese piano teaching system for beginners.

In addition, the American teacher chooses the most suitable teaching materials to guide the individual student rather than having all the students use the same type of materials. There are now many excellent method books available.

c. Syllabi for Advanced Music-Related Classes

In higher education in the United States, the teacher is required to provide a syllabus. Although it is a relatively new requirement, it has been widely applied in most schools. The syllabus is expected not only in the academic courses, but also in courses like the private piano lesson. It can be considered a road map or a guidebook, which leads students to understand the overall goals and requirements of a class. It also shows that the teacher has devoted detailed efforts to create the course.

As I remember university in China, we did not have syllabi for any of our classes. From what I know of current China, the syllabus is still not commonly used yet. Only a few schools have started to apply the syllabus, like the Wuhan Conservatory of Music.

Here I have included a sample syllabus for Piano Literature I :

Instructor: Xueli Liu

Email: [email protected]

Office Hours: Tue 9:00-10:30am

(Please email to establish an appointment outside of office hours.)

It gives a general idea of what contents a teacher should include in a syllabus. (I created this syllabus as an assignment in the “The Teaching Performer” class, taught by Dr. Lani Hamilton, at UMKC. It is the result of research that examined many syllabi, including those for history classes, piano literature class, and Dr. Hamilton’s sample syllabi. The syllabus that follows was accepted as an assignment in the class.)

Course Description:

This course is designed to enhance the knowledge, appreciation, and understanding of piano literature from the late Renaissance to Romantic period. The participation and team presentation require the students' take part in the class as much as possible and demonstrate what they have learned from the class. You will discover some music which you did not know before, and gain new insights into works with which you were already familiar. By the end of the course, you should have a comprehensive understanding of the development of the piano, a wide variety of composers, genres and styles, and corresponding works through reading, analysis, listening. presentation, and exams.

Student Learning Outcomes:

- Students will discover a great amount of music from Renaissance to Romantic period.

- Students will understand the developmental history of the piano.

- Students will know a wide variety of composers.

- Students will explore as many as genres and styles possible.

- Students will identify music by ear and by score.

Requisite Materials:

- Magrath. Jane. The Pianist's Guide to Standard Teaching and Performance Literature. California Alfred Pub. Co., 1995.

- Gordon, Stewart. A History of Keyboard Literature: Music for the Piano and Its Forerunners, New York: Schirmer Books, 1926.

Some scores are available in PDF format on the listening list posted on Blackboard. NOTE: Students will be asked to purchase some scores as needed. Like Mozart Sonatas, and Beethoven Sonatas. My assumption for serious musicians who will be interacting with this music for a lifetime should make a long-range plan to build their own library.

Assignments

Responses to Readings and Team Presentations

Responses to Readings:

- For ten of the assigned chapters or articles, please submit a two-paragraph response for each on Blackboard These are due the day for which the chapters are assigned weekly. Your responses should convey one paragraph brief summary of the content and the other paragraph is your subjective response to it.

Team Presentations:

- Presentation No. 1 Representative Works Review from 1600-1750

- Presentation No. 2 Representative Works Review from 1750-1900

In groups of two people, prepare a fifteen-minute oral presentation on two representative works from each of the above appointed time-period. Each group member chooses one work, then analyses and compares the two works together. It could include any information related to the piece, e.g. compositional background, form, genre, special character, specific terms, etc. But the content must be compact, and points have to be related closely. During your comparative analysis of the two works. Nate what you think is similar or different, and what made them significant. This should be a group presentation in the form of a dialogue with appropriate musical examples, and must include a typed handout. You can either play the excerpts of recordings or play by yourself. Your handouts should not be a copy of the text that you read in front of the class, but should outline the main points and include other relevant information that is better transmitted visually than verbally. Each person must contribute meaningful content to the presentation. You will want to meet as a team in advance to plan your presentation. These two presentations will happen respectively two weeks before the midterm and final exam.

Attendance:

- 1-2 unexcused absence ----- No impact

- 3 - 4 unexcused absences ---- Final grade drops 1/3 of a GPA per absence (ex. A to A-, A- to B+)

- 5+ unexcused absences ---- Automatically count as Grade F

| Grade | A | A- | B+ | B | B- | C | C- | D+ | D | D- | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Points | 93 - 100 | 90- 92 | 87- 89 | 83- 86 | 80- 82 | 73- 76 | 70- 72 | 67- 69 | 63- 66 | 60- 62 | 0-59 |

Participation (includes the following):

- Have all the proper materials

- Clear preparation of the given reading assignments for that day

- Thoughtful in-class comments on the music and/or reading (either volunteered or when called upon)

- Respectful relationship with your classmates/peers

- Asking appropriate and thoughtful questions as they arise

Listening exams: (five excerpts for each exam):

- Be able to identify by ear the works on the listening list (the list is the accumulation of works that we listened in the class).

- Be able to give the name of composer, genre, form, and special features.

Listening List I (Listening Exam I and Midterm):

- Handel,

- Bach,

- Couperin,

- Rameau,

- Scarlatti,

- Sons of Bach,

- Haydn

Listening List II (Listening Exam II and Final Exam ):

- Mozart,

- Beethoven,

- Schubert,

- Mendelssohn,

- Schumann,

- Chopin,

- Liszt,

- Brahms

Exams: (scores identification, term explanation, possible essay):

[Exams are based on material covered in class: text readings and PowerPoint slides.]

- Be able to identify by score the works on the listening list.

- Be able to identify salient features about the works. Be familiar with musical terms.

- Be able to identify by ear the works on the listening list (the list is the accumulation of works that we listened in the class).

- Be able to give the name of composer, genre, form, and special features.

In my opinion, every teacher should try to design her own curriculum according to their school’s rules. Syllabi usually contain the overall course description that demonstrates what the class is about; required materials that the teacher will teach or the resources available for the students; assignments including papers, presentations, projects, and examinations with percentage ratio; attendance policies that give students a clear sense of the disciplinary possibilities; how the grade is determined, and other additional information. Sometimes, teachers might also provide the class calendar with specific topics and date. These chosen materials and methods can be used for the entire semester.

Although a syllabus might require an occasional change as the class progresses, having a syllabus keeps both teacher and students more organized and efficient through the semester.

Four Differences in Specific Pedagogical Approaches in Private Piano Teaching between the United States and China

A private piano lesson usually lasts 45 to 60 minutes in both America and China. While there will be differences in details, the most common procedure in a lesson has the student performing first, followed by the teacher’s response, the student and teacher work together, reinforcing the lessons to be learned. However, there are still some specific dissimilarities in pedagogical approaches between the United States and China due to cultural differences. Based on my experiences, these usually involve verbalizations, modeling, and behaviors in the piano lesson. I will discuss four particular areas regarding feedback, questions, demonstration, and physical contact.

a. Positive Feedback vs. Negative Feedback

Feedback from the teacher is an essential part in a piano lesson. It is either a word or an action, and it either influences a behavior or not. Feedback can be as simple as the teacher saying “go on” or “good job” after the student’s playing, or the teacher might scowl.

According to Duke (2009), feedback serves two purposes: it can provide information and motivate behavior. (Ibid., 122-124) Feedback is not given only in response to what students do; the more important result is that it can guide students to attain more successful tasks.

In general, I find that American teachers give more positive feedback than Chinese teachers. It might be because Americans believe it is important to encourage the student in the teaching process. Even if the quality of the answer is poor, the teacher will positively affirm the student’s fearless participation and hard work first. Therefore, American students are usually more confident than Chinese students.

In China, teachers do not commend the student unless the response really satisfied their expectations. In addition, direct negative feedback, such as “you played this section very badly”, is quite common in Chinese piano lessons.

Although it is clear feedback, it may potentially hurt the student’s confidence. But negative feedback can also be very useful. It not only gives an honest response, but it helps build up a person’s ability to bear a psychological blow; it toughens the student. A great teacher should build a students’ confidence so that they can overcome mistakes and setbacks during their study process. I believe that a teacher is not just one who imports knowledge; she is also a mentor who inspires her students regarding life philosophy.

In my opinion, there is no right or wrong answer about whether feedback should be positive or negative. It is all about the balance and the timing of the feedback as it is needed in a lesson according to the teacher’s judgement. The personality of the student also affects the ratio of positive and negative feedback. If the student is a sensitive person, positive feedback may be more useful than negative feedback.

While the teacher’s feedback points out certain aspects of the students’ behavior, it also controls the number of opportunities the student has to produce results, thereby increasing the teacher’s opportunity to give feedback. Therefore, teachers should provide feedback frequently since it gives students more opportunities to respond, improve their work, and lets them get used to dealing with mistakes. This is called purposeful feedback, which is a powerful pedagogical skill. (Ibid., 134-137)

b. Encouraging Questions in Lesson

In terms of teaching customs in a piano lesson, there are similarities in teachers’ verbalizations in a piano lesson between America and China. However, American teachers usually ask more questions during a lesson. This reflects the Americans’ preference to verbalize rather than model in the piano lesson according to Davidson’s article. They prefer to speak about concepts like hierarchical structures and organizational schemes. (Davidson 1989, 96-97) In contrast, American students like to respond verbally to the teacher’s questions, as well as ask more questions. Teachers usually encourage students to ask a question, whether it is a good or bad question. Moreover, they like to inspire and lead the students to think of the answer instead of just telling them directly.

In China, students were taught in a classroom that was highly disciplined. Unlike in America where students often speak whenever the class is going on, Chinese students are only allowed to speak by raising their hand and waiting for the teacher to call on them (at least in my generation). Also, the student is very embarrassed if s/he presents a wrong idea. As a result, Chinese students are quiet and tend to follow the teacher’s instructions without questioning. There is a saying in old China (another old Chinese folk saying that I have translated):

A student is an empty vessel into which the teacher pours information and skills. 老师的授业解惑就如同往容器里倒水一般.”)

In my opinion, asking students questions can be vital to their learning. For instance, one can ask the student if he feels the difference between the old way he played and the new way he just learned. Or what tone color he thinks is best for the piece? As a teacher, I have learned that one should foster in the student a habit to think about why to do something and how to achieve it, rather than simply telling them what to do. Students cannot rely on the teacher to help them deal with every problem; they need to be able to think independently, to discover the solution to analogous problems. Then they can solve problems as they arise by themselves.

c. Demonstration vs. Verbalization

Generally speaking, teachers often demonstrate and play along with students to model correct performance in a piano lesson. They “show” rather than “tell.” The effectiveness of teacher modeling is determined to some extent by the specific demands of each instructional situation. Individual students require varying playing models at different points.

According to my experiences and observations, Chinese piano teachers like to play a lot more than talk to demonstrate something, no matter if they play both hands or just the melody with one hand. Also, they present their ideas through diverse demonstrations, using such tools as gestures, singing, or playing simultaneously along with the student. In a master class at the Shenyang Conservatory of Music, for example, a young student played the opening of the Japanese melody “Sakura” (667-, 667, 6717, 6764…). The teacher sang loudly while he played “Da, da, di---,” then softly, “da, da, di---Loud, then soft, an echo.” (Davidson 1989 , 86-87) Demonstration is also used to transmit basic technical skills in Chinese piano teaching, such as training the hand shape and finger independence.

American teachers tend to verbalize more compared to Chinese teachers. According to Davidson, Americans prefer to discuss music in terms of basic elements (e.g. pitch, rhythm, timbre, and motive), formal structures, and physical properties. American teachers are more likely to emphasize things like the tradition from which the piece comes, the style of the period, and even the nationality of the composer.

The notational representation of a piece is only a reference to the music, not the musical content itself. (Ibid, 96-97) When it comes to the Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude, the teacher will mention Chopin's feeling about the fall of Warsaw and the failure of the revolt, and the agitated melodies implies the shouting and resistance of the Polish people.

Besides demonstrating technical difficulties and how to express the music, I believe verbalizing some musical analyses and the background of a piece can be significant in piano study. Playing a composition is like composing the piece a second time; the performer’s thoughts and ideas become part of the original musical material. The notes themselves on the score do not have meaning, but the composer and performer give them meaning. When students have knowledge of theory skills and background information on the piece and the composer, they definitely will understand and perform a piece better.

d. Using Physical Contact to Teach

Another critical component in piano teaching is the use of physical contact. Since piano playing is a highly complex physical activity, even the smallest bad habit can involve tension, or if a posture problem develops, serious performance-related injuries can occur. The most common issues are tendonitis, focal dystonia, and cervical disc herniation. I am the victim of cervical disc herniation due to many years of concentrated daily practice without correcting the wrong posture. Therefore, it is vital for teachers to show students correct posture during the process of piano study.

The teacher can use physical contact to identify motion and tension, thus giving the students a direct experience of motion awareness. This instruction can lead to the players developing the correct physical habits or help them with movement retraining, especially with beginners.

For instance, when I was an undergrad and had trouble playing strong chords using the body’s strength, my teacher would play the chords on my shoulder to let me feel how the fingers stand, how the wrist moves, and how the strength comes from the entire body.

Another example is my teacher had me put my hand above her hand while she played the two-note slur in order to show me how the wrist drops and lifts. This is a very normal teaching practice in China. The teacher will demonstrate many skills by using physical contact to explain and impart the direct sensation. Usually, there is no need to ask for permission to touch in advance.

American teachers use less physical contact during piano teaching. In the last decade many schools have a “no touch policy” to avoid the possibility of a harassment charge. However, teachers are allowed to use physical contact if they get parents’ or students’ permission. It still requires the teacher to be considerate and very cautious. The teacher can also use other strategies to replace physical contact, like demonstrating on another piano for the student to imitate.

From my perspective, I understand why American teachers are reluctant to use physical contact with students in a piano lesson. But sometimes, demonstrating by touching is necessary and much more efficient than talking. The teacher should be able to explain the physical contact and how they use touch in the lesson syllabus.

Group Piano Settings and Studio Classes

In the United States, there are different settings for group piano teaching. The practice of teaching piano students in groups started last century and has been advocated by many professionals in piano education. There are three usual settings for a group class: a class for beginners ages six to ten, usually taught by non-college teachers; the group class for undergraduate non-piano students (instrumental and voice majors) in a music school, which is a required keyboard-skills course; and the studio class for piano major students, in which the private instructor sees all his/her students in a group setting once per week.

I will mainly discuss the group class for keyboard-skills and studio class in this paper.

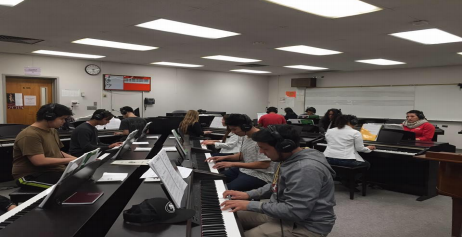

Piano classes for pre-college students began in the early decades of the 20th century. During the 1960s, piano programs for beginners, affiliated with university pedagogy programs, appeared throughout the United States. (Pike 2013, 213-227) The keyboard-skills class is usually offered to students who do not have prior experience at the piano. Generally, the class is in the digital piano lab, which is usually equipped with at least six digital pianos with headphones and MIDI sequencer, a Keynote Visualizer, a Controller unit, a screen and 3D projector, an upright acoustic piano, and whiteboards with staves:

Group-piano class and studio class are very popular in the United States; however, it is not common in China yet. Using my own study experience as an example, I started taking piano lessons when I was four years old. My piano teacher came to my home to teach me once a week. When I was in my high school and as an undergrad at the Sichuan Conservatory of Music, I always had one private piano lesson each week. I did not know either group-piano class or studio class until I came to the United States for my master’s degree. I did not get used to the new system at first, but was amazed by the different teaching methods.

After years of experience, I have come to deeply respect the benefits of group-piano and studio classes. There are so many advantages attainable in the group teaching setting that it is worth consideration as a technique to be absorbed into Chinese piano teaching system.

For students, there are a lot of benefits of participating in group-piano class. Firstly, it takes advantage of modern technologies, such as the keynote visualizer and headphones. These tools help the students watch the teacher’s demonstrations and allows them to listen to their own playing more easily. Secondly, it allows the group to learn basic piano skills together, which usually motivates students.

I believe people see their progress when comparing themselves to others. If they learn something together, some students might be glad when they do better than others, or some students might have more motivation to try their best in order not to drag the whole team down.

Furthermore, there are various learning activities that they can discover together: technique, theory, sight reading, ear training, harmonization, transposition, improvisation, and games. For instance, students can be divided into small groups to play different parts of one chord or one piece. They will make music with peers and learn how to cooperate with others. Also, one group could be “the teacher” when another group does one activity. Hence, the student gets the chance to be “a teacher,” to analyze the music and learn from self-examination. Those are the comprehensive benefits of group piano study that the students cannot experience in a private piano lesson.

Compared to the group-piano setting, the private piano lesson is still the most recognized teaching method in China and it does contain many advantages. At each lesson, the teacher will work with one student at a time through the music, provide a review of the previous lesson, solve problems that appear in the lesson, and then teach new skills and perhaps a new piece. Each lesson includes many relevant activities to pursue the lesson goal. Unlike group-piano class, the private piano lesson is student-centered, so the teacher is more able to focus on the activities of what the student did.

Since the private lesson has only one student, it allows the teacher to reinforce any targeted skills as needed. Some students lack motivation to practice on their own; the private lesson setting will easily expose whether the student has practiced their homework between weekly meetings. As a result, this kind of weekly lesson has been preferred by students and parents in past decades. However, there are disadvantages compared to group-piano class. For example, a private lesson does not have group participation, which means no ensemble music-making. Students are taught as individuals, so there is no chance to participate, communicate or listen to another person.

While faculty members may lead class-piano, graduate assistants, usually masters or doctoral students, often can gain experience by teaching the class under the professional pedagogue’s direction. Teaching these classes can be part of the pedagogy curriculum with guidance and professional suggestions provided by the faculty member. The skills needed to be an outstanding private lesson teacher are not the same for teaching a group piano class, where one needs a rigorous syllabus and the ability to focus on every individual student within the group. The teacher needs a totally different set of teaching strategies than for a private lesson.

Assigning the graduate-assistants to teach group-piano class gives the novice teachers an opportunity to accumulate fundamental experiences for their future. It also prevents the problem of students who just graduate from university not having teaching experiences.

In the United States, many notable piano educators have written methods books and materials for group-piano teaching, such as Christopher Fisher’s Teaching Piano in Groups, Sylvia Coats’ book Thinking as You Play: Teaching Piano in Individual and Group Lessons, and Alfred’s Group Piano for Adults by E. L. Lancaster and Kenon D. Renfrow. The Alfred book was translated into Chinese in 2015. I heard from a colleague who was just back in China last year that many universities have started to use this book to provide group-piano class to non-piano majors as America does.

In the United States, studio class is very common; however, it is not yet popular in China. There was only a performance jury at the end of each semester when I was in Sichuan Conservatory in China around the year of 2010.

In America, I have learned that studio-class is offered once a week. It is also possible that all studios of each department will gather together monthly, sometimes called “seminar.” Studio class offers students a fantastic opportunity to perform and discuss various subjects relevant to practice and performance. The student can report from the stage what they have learned and practiced off stage.

By listening to others’ playing, students can learn much more repertoire. It gives students chances not only to perform, but also to learn from each other. The studio-class setting exactly demonstrates the old Chinese saying (that I have translated here):

In music study, ‘listen more’ and ‘watch more’ are better than only ‘practice more.' [学音乐不仅需要‘多练’,还需要‘多听’‘多看.]

The atmosphere of studio class is social and supportive, much like a big family. Everybody can offer friendly comments and receive feedback after playing. Any kind of performance, good or bad, can be seen as a learning experience. This is a valuable time to watch and learn for the process of preparing juries and recitals. It can also improve students’ listening skills. Under the professor’s supervision, students learn how to listen and analyze a piece, including background, form, interpretation, and critical thinking.

Conclusion

In this paper, I summarized similarities and differences between methods of piano teaching in the United States and China. One can learn a lot by analyzing the advantages and disadvantages inherent in both countries. America has a longer history with its Western musical background, but China as a new rising country is undergoing rapid development, placing many great musicians on the international stage. Chinese people love to accept and develop Western music despite its recent introduction to China in the last few decades.

Students experience piano study quite differently. Particularly interesting are the disparate teaching theories between America and China and how this is reflected in teaching styles, teaching materials, and the syllabi. Furthermore, there are differences in pedagogy strategies in private piano lessons with regard to feedback, question, modeling and physical contact.

Finally, teaching in groups, whether it will be group lessons, class piano, or studio class, is new in many institutions of Chinese education. Music educators can learn a lot by comparing these approaches, having more awareness of differences and advantages between the two countries to achieve more well-rounded, effective teaching.

References

- Agay, Denes. 2004. Teaching piano: A Comprehensive Guide and Reference Book for the Instructor. New York, NY: Yorktown Music Press, Inc.

- Benson, Cynthia, and C. Victor Fung. 2005. “Comparisons of Teacher and Student Behaviors in Private Piano Lessons in China and the United States.” SAGE journals: International Journal of Music Education 23, no. 1 (April ): 63-72. Accessed March 15, 2018.doi

- Bonadio, Jocelyn. 2012. “China’s Embrace of Western Classical Music: A Timeline.” WQXR Features: New York Public Radio (January). Accessed July 22, 2018. wqxr

- Campbell, Patricia Shehan.1989. “Orality, Literacy and Music’s Creative Potential: A Comparative Approach. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education.” JSTOR: Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, no. 101 (Summer): 30-40. Accessed March 24, 2018. jstor

- Coats, Sylvia. 2006. Thinking as You Play: Teaching Piano in Individual and Group Lessons. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Comeau, Gilles, Veronika Huta, and Yifei Liu. 2014. “Work Ethic, Motivation, and Parental Influences in Chinese and North American Children Learning to Play the Piano.” SAGE journals: International Journal of Music Education 33, no.2 (February): 181-194. Accessed March 23, 2018. doi

- Davidson, Lyle. 1989. “Observing a Yang Ch’in Lesson: Learning by Modeling and Metaphor.” JSTOR: The Journal of Aesthetic Education 23, no. 1 (Spring ): 85-99. Accessed March 21, 2018. jstor

- Dearing, Eric, Kathleen McCartney, Heather B. Weiss, Holly Kreider, and Sandra Simpkins. 2004. “The Promotive Effects of Family Educational Involvement for Low-Income Children’s Literacy.” Elsevier: Journal of School Psychology 42, no. 6 (November-December): 445-460. Accessed March 25, 2018. doi

- Duke, R.A. 2009. Intelligent Music Teaching: Essays on the Core Principles of Effective Instruction. Austin, TX: Learning and Behavior Resources.

- Kuzmich, Natalie. 1995. “Canada and China: Beliefs and Practices of Music Educators: A comparison.” OML: Canadian Music Educator 37 ( no. 1 ): 31-35, Accessed August 3, 2018. openmusiclibrary

- Lewis, Rebecca. 2003. “The Time is Now (Forum Focus: Arts Awareness and Advocacy).” JSTOR: American Music Teacher 53, no. 3 (December): 56-57. Accessed March 25, 2018. jstor

- Melvin, Sheila. 2016. “How China Influenced Western Classical Music,” Caixin (May 2016). Accessed August 1, 2018. caixinglobal

- Pike, Pamela D. 2013. “The Differences Between Novice and Expert Group-Piano Teaching Strategies: A Case Study and Comparison of Beginning Group Piano Classes.” SAGE journals: International Journal of Music Education 32, no. 2 (November): 213-227. Accessed March 19, 2018. doi

- Randel, Don Michael. 1986. “Education in the United States.” In The New Harvard Dictionary of Music, 276-278. London/Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Siebenaler, J. Dennis. 1997. “Analysis of Teacher-Student Interactions in the Piano Lessons of Adults and Children.” SAGE journals: Journal of Research in Music Education 45, no. 1 (April ): 6-20. Accessed March 22, 2018. doi

- Slaton, Emily Dawn. 2012. “Collegiate Connections: Music Education Budget Crisis.” SAGE journals: Music Educators Journal 99, no. 1 (September ): 33-35. Accessed March 23, 2018. doi

- Stanford, Grace Ann. “History of Music Education in the United States.” EduNova: Innovations from Leading Education Experts. Accessed July 18, 2018. edu-nova

- Stevenson, H. W. and Lee, S. Y. 1990. “Contexts of Achievement: A Study of American, Chinese, and Japanese Children.” JSTOR: Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 55 (no. 221): 66-67. Accessed August 3, 2018. jstor

- Stern, Isaac. 1999. My First 79 Years. New York: Alfred A. Knopf: Distributed by Random House.

- Su, Xiaohuan. 2002. Education in China: Reforms and Innovations. Beijing: China Intercontinental Press.

- Yoon, Jenny Nam. 2000. “Music in the Classroom: Its Influence on Children’s Brain Development, Academic Performance, and Practical Life Skills.” M.A. Thesis., Biola University, 2000.

- Zhou, Mingming, Weiji Ma, and Edward L. Deci. 2009. “The Importance of Autonomy for Rural Chinese Children’s Motivation for Learning.” Elsevier: Learning and Individual Differences 19, no. 4 (December): 492-498. Accessed March 20, 2018. doi