#7 Poetry and Music of Medieval Azerbaijani Ashygs in the Context of Mystic Practices

UDC: 7.033.3(479.24)"14/15"

COBISS.SR-ID 229887756

Received: November 15, 2016

Reviewed: February 13, 2017

Accepted: February 15, 2017

#7 Poetry and Music of Medieval Azerbaijani Ashygs in the Context of Mystic Practices

Citation: Baghirova, Sanubar. 2017. "Poetry and Music of Medieval Azerbaijani Ashygs in the Context of Mystic Practices." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 2:7

Acknowledgement: The author is pleased to thank Professor Maharram Gasimli for sharing his knowledge of some ancient Azerbaijani words and terms with me, Professor Chingiz Qajar, corresponding member of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, for giving me the photos of the old Dervish khanegah in Nakhchivan, ashyg Ramin Garayev for giving me the ashyg song Urfani in his rendition, and ashyg Mehemmedeli Meshediyev for e-mailing me the recording of the ashyg song Ibrahimi.

Abstract

This article focuses on poetry and music of the medieval Azerbaijani ashyg in the context of mystic practices. The ashygs are the bearers of the syncretic art form that came into being at the end of the 15th – early of the 16th centuries and has reached to date. Both medieval and modern ashygs – ustads (masters) were and are poets, composers and performers in one person. Poetry of early medieval ashygs, such as, Dirili Gurbani, Miskin Abdal (15th-16th century), Abbas Tufarganly, Khaste Gasym, Sary Ashyg (17th century) was thought to convey the God's message; these ashygs called themselves ‘haqq ashiqi’, that is ‘those who fell in love with Truth’ meaning by Truth the Higher Principle, the Absolute. Some of the early ashygs, for instance, Dirili Gurbani and Miskin Abdal, were Sufi mystics and members of Sufi brotherhoods. Poetry and music of the medieval Azerbaijani ashygs was often a part of the Zikr, the mystic musical rites of sama' practiced by various Sufi dervish orders. A number of songs from the repertoire of modern ashyg sometimes are called ‘samavi havalar’ (sama' tunes) and do sound particularly archaic; it is believed to date back to the music performed at sama'. In the 19th century the art of ashyg lost its ideological function but religious and mystical motifs remained an inspiration for the ashyg even in the 20th century. These motifs were mainly associated with the name and cult of Imam Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, and the Twelve Imams. Core notions of the article are: Ashyg, ’haqq ashiqi’, sama', zikr, madh, meddah of Imam Ali, mürid, mürshid, khanegah, tekye.

Sufi poets, spiritual tunes, Azerbaijani ashyg songs, diviani poems, dervish mystic musical rites

Introduction

This article is aimed to draw attention to ashyg music in medieval spiritual dervish practices. The art of ashyg is one of the most ancient art forms in Azerbaijan, as well as the mugham music. The investigation of Poetry and Music of medieval Azerbaijani ashyg in the context of medieval mystic practices is a part of the bigger work that is supposed to cover the role of Azerbaijani traditional music, in particular, poetry and music of ashygs and mughams in Sufi and Shia spiritual rites in XVI-XX centuries.

Medieval Sufi Poets

The Sufi mystic teachings and spiritual practices started expanding in Azerbaijan around the 10th century. Sufism is a mystical dimension of Islam. Encyclopaedia Britannica defines Sufism as:

mystical Islamicbelief and practice in which Muslims seek to find the truth of divine love and knowledge through direct personal experience of God. It consists of a variety of mystical paths (...). Islamic mysticism is called taṣawwuf (literally, “to dress in wool”) in Arabic, but it has been called Sufism in Western languages since the early 19th century. An abstract word, Sufism derives from the Arabic term for a mystic,ṣūfī, which is in turn derived from ṣūf, “wool,” plausibly a reference to the woollen garment of early Islamic ascetics. (Sufism, Encyclopedia Britannica)

Among numerous Azerbaijani mystics of the Early Medieval period we should mark the names of those Sufi as the most outstanding: Abu Said (d. 1050), more known under the name of Baba Kuhi, his brother Husein Shirvani (d. 1072), as well as Shihabaddin Sukhravardi (1144-1234), the founder of the zahidiyya order, Sheikh Safiaddin Ardabili (1252-1334), the founder of the safaviyya order, Shihabaddin Fazlullah Naimi (1339-1393), the founder of the hurufiyya order, and many others. Sufi orders or brotherhoods were “fraternal groups centering around the teachings of a leader-founder”. (Ibidem)

According to Azerbaijani scholars, some of the famous Sufi brotherhoods, in particular ahi, qadiriyya, suhravardiyya, halvatiyya, hurufiyya, zahidiyya, safaviyya, roushaniyya and gulshaniyya, were formed exactly on the territory of Azerbaijan (Məhəmmədcəlil and Xəlilli 2003, 10). Since the Sufi teaching often found expression in poetical and literary images, many medieval mystics were known mainly as poets and writers. Among the Azerbaijani mystics the most renowned Sufi poets were Fazlullah Naimi, Qasim Anvar (1356-1433), Seyid Ali Imadeddin Nasimi (1369-1414), and Shah Ismayil (1487-1524) from the Safavi dynasty, active under the pen name Khatayi. Sufi ideas can be traced in the writings of the outstanding Azerbaijani poet Muhammad Fuzuli (1494-1556), and a great many other medieval Azerbaijani poets and writers.

Poetry and Music of the Azerbaijani Ashyg

The Turkic Sufi poet and mystic Ahmet Yasavi (1105-1166) founded the order yasaviyya, dervishes which called themselves the ashiqs of the Truth (Ashiq, derived from the Arabic word ashq, i.e. “love”, or eshq in Azerbaijani pronouncement, is translated as “being in love, having loved”. Thus, the ashiq of the Truth was supposed to mean the “lover of the Truth”), and the servants of the Truth, meaning by the Truth the higher principle, the Absolute. The fragment from the poem by Ahmet Yasavi cited below is the one where the word ashiq is used for the first time as the form addressing to the dervish:

Haqq qulları dərvişlər,

Həqiqəti bilmişlər,

Haqqa aşiq olanlar

Haqq yoluna girmişlər

Dervishes, servants of the Truth,

Learned the Truth,

Having loved the Truth,

Stepped on the righteous path.

("Divani Hikmet" / Divine Wisdom by Ahmad Yasavi,

quoted in Qasımlı 2007, 92. Translation by the author.)

This poetical expression, «haqqa aşiq olanlar», literally meaning “those who have loved the Truth”, has given a name to a unique phenomenon in Azerbaijani oral literature, which originated at the end of the 15th century and reached its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries. We are talking about the poetry and music of the Azerbaijani ashygs – mystics who called themselves haqq aşiqi, i.e. the ashiqs of the Truth, the ones who ”have loved the Truth”.

Mən haqq aşiqiyəm, haq yola mayil,

Kitabım Qurandır, olmuşam qayil.

I am an ashiq of the Truth, who has loved the righteous path,

My Book is Koran, and I have put my faith (in it).

(Əlizadə 1995, 271. Translation by the author.)

These lines are from a poem of an outstanding ashyg Dirili Gurbani (b. 1477), one of the constellation of haqq aşiqi, whose spiritual, as well as poetical, status has been admired hitherto. Different spellings of the words ashiq and ashyg reflect their different pronunciations and meanings: ashiq means “lover, fallen in love,” while the word ashyg refers to the bearer of the syncretic art form that originated at the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries and has preserved its attractiveness for Azerbaijanis to date.

The ashygs, both medieval and modern, mainly those called ustads (masters), are poets, composers and performers in one. (More about the art of Azerbaijani ashygs see Baghirova 2015, 116 – 140). The constellation is represented in the names of Dirili Gurbani, Miskin Abdal (15th-16th centuries), Abbas Tufarganly, Khaste Gasym, Sary Ashyg (17th century). The stories of life and love of haqq aşiqi formed the plot of the medieval ashyg dastan, big music and literature composition of oral epic literature. On some haqq aşiqi, main characters of some popular medieval dastans, such as “Ashyg Garib”, ”Seidi and Peri”, Novruz and Gandab”, “Yetim Aidyn”, there is no other evidence of their historical presence except of the dastans themselves. The ashiq of the Truth have often personified their divine love in the image of the fair lady. As the author wrote previously in one of her works:

The story of a haqq aşiq meeting his fair lady, searching for her, and worshiping her can be interpreted as an allegory of the search for the Truth and divine Love. (Baghirova 2015, 123)

Wherein in the lyric poetry of the haqq aşiqi, as well as in classical Sufi poetry, some metaphors, epithets and comparisons can be interpreted doubly – whether one is talking about divine or earthly love. A great example of this poetic language is given in the poem of Shah Ismayil Khatayi:

Məhəbbətdir yerin-göyün dirəyi,

Məhəbbət edənin yanar çırağı,

Aşiqin beytullah-məşuq durağı,

Haq nəzər etdiyi yerdir məhəbbət.

Love is the pillar of the earth and sky,

The lamp of the loving one is (always) lit,

The house of the beloved is the place of worship for the

loving one.

Truth remains where love is.

(Qasımlı 2002, 55. Translation by the author.)

Ashiqs of the Truth appeared in medieval love dastans as poets and musicians whose talents were given them by a mystical higher force, the kind of talent called in Azerbaijani ilahi vergisi, “the Gift of God”. It was believed that they were holy people under the God's protection. Though in the 19th century the art of the ashygs lost its Sufi ideological ground, the idea of the sacral origin of the ashyg art has remained popular with Azerbaijani people to date.

Sufi Dervish Rites

Besides of mystical ideas and motifs emerging in early ashyg poetry, a number of haqq aşiqi were known in history of literature as mystics and members (mürid) of various Sufi dervish brotherhoods. One of such brotherhoods, the safaviyya order, headed by Shah Ismayil Safavi, had the ashygs and poets among its members, the most known of which was ashyg Gurbani. Shah Ismayil Khatayi, sheikh of this order and the Sufi poet, patronised a poetic mejlis (literary society, circle) at his court, and some members of this circle recognized him as their spitirual leader as well, the mürshid. So was ashyg Gurbani, who in his famous poem written on the death of Shah Ismayil noted him as his mürshid:

Fələk, sənlə uruşmağa bir qabil meydan ola,

Tut əlimi, fürsət sənin, kaş belə ehsan ola.

Getmiş idim mürşüdimə dərdimə dəva qıla,

Mən nə bilim, mən gəlincə xaki ilə yeksan ola.

Fate, there is no field where one can fight with you,

Take my hand, this chance is yours, I wish I had this gift.

I came, troubled, to my mürshid to ask for help,

How did I know that before I arrived he had turned to dust.

In his another poem Gurbani applied to Shah Ismayil with the following words:

Mürşidi-kamilim, sheikh oğlu şahım,

Bir ərzim var qulluğuna, şah, mənim

My perfect murshid, the son of sheikh, shah,

I have something to ask you, shah.

(The poems quoted from the author’s memory)

The mystic in the status of abdal, i.e. saint, (Abdal was a mystic who reached the high level of holiness, a rank of saint, who was thought to be appointed by Allah as a”Friend of God”) was Seyid Husein, another major poet-ashyg of the epoch of Shah Ismayil, his elder contemporary and friend, known in history of Azerbaijani literature with the pen name of Miskin Abdal (1430-1535). So was Shah Ismayil Khatayi, who sometimes signed his poems with the takhallus (pen name) Abdal Khatayi:

Xətayiyəm, bir haləm,

Əlif üstündə daləm,

Sufiyəm təriqətdə,

Həqiqətdə abdaləm

I am Khatayi, the one,

Who is the letter dal for the letter alif,

I am a Sufi in Tariqat and

The Abdal of Truth.

(Xətayi, 1988, 327. Translation by the author.)

The letter alif or alef (A), the first letter of the Arabic alphabet, is usually attributed to Allah while the letter dal (D) because of its arched shape is often used as a metaphor for a man with a body bowed down. These lines may be interpreted as an allegory of the relationships between God and human being, Allah and dervish. Tariqat (literally ‘way’) is a mystic way of self-improvement, a kind of individual spiritual journey for the seeker of God to attain His presence, to join Him. Various Sufi orders distinguished their own forms of tariqat, which were not like each other.

It is known that many of Sufi dervish brotherhoods practiced collective devotional meetings, collective meditations called zikr. They usually had special places for these meetings named tekke (also tekye and tekyegah) or dervish khanegah where dervishes lived and held their rites. The word zikr (often spelled as dhikr) means “to mention”; it reflects the goal of this rite as “to remember” God's name. Zikr were often accompanied with music and singing of spiritual poems, and sometimes with ecstatic dancing. This poetic and musical part of zikr was a rite known as sama` (literally, "listening" that was usually understood as "listening to music"). Sama' was practiced in many Sufi dervish orders. Its purpose was to intensify dervishes' meditation, to make their senses particularly acute, and thus to help them reach the state of spiritual ecstasy at which they felt like having attained God's presence. Turkish scholar Abdulbaki Gölpinarly noted that:

almost all of Sufi dervish tariqats naqshbandiyya welcomed singing poems and songs (ilahiler), playing def (a kind of tambourine), and dancing during their zikr rites. (Gölpinarly 1985, 134)

Zikr of Mevlevi dervish order went (and still goes) with accompaniment of such musical instruments as woodwind instrument nei (a kind of flute), or various string instruments like lute. According to the renowned Azerbaijani scholar professor Maharram Qasimli, and a few other authors, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries among the string instruments used in the rites of Sufi dervishes-ashiqs one of the major was chagyr (also chovur, or chagur). Referring to the work of Ali Reza Yalchin, Qasimli writes that ”chagyr accompanied singing of samayi, nefes and other spiritual melodies” (Qasımlı 2007, 120).

One has to note that both samayi and nəfəs (also haqq nəfəsi, ilahi nəfəsi or pir nəfəsi) are also poems of spiritual content; they usually carried Sufi ideas and were thought to convey God's word. The melodies composed to these poems were known as samayi havaları, i.e. melodies performed at sama`.

Listening to music was also a part of zikr rites of the safaviyya Sufi order. Chinqiz Sadiqoqlu in his work on safaviyya dervish brotherhood notes that Sheikh Safiaddin Ardabili (XII century), the founder of this order and the Shah Ismayil Khatayi's ancestor, often invited singers and musicians to perform at zikr, and the traditions of listening to music and ecstatic dancing, the sama`, were continued by his successors (Sadiqoqlu 1988, 62).

We may admit that the rite of sama` survived to the time of Shah Ismayil, and those of ashyg-mystics and poets who considered themselves to be his mürids probably took part in such meetings. Maharram Qasimli thinks that:

Tekke rites brought about a number of new melodies. Some of these spiritual tunes, which were composed to be performed at Sufi dervish rites with accompaniment of chagyr, have reached to date taking a significant place in the repertoire of modern ashygs, now being performed with accompaniment of saz. (Qasımlı 2007, 120-121. Saz is the principal musical insturment of the Azerbaijani ashyg, a long necked lute.)

Many of the contemporary Azerbaijani ashygs, ustads, (masters) share the point of view that some melodies from the classical ashyg repertoire, including such songs as Shah Khatayi, Bash divani, Heydəri, Ibrahimi, Sultani, and a few others, were probably composed by ashyg Dirili Gurbani. The late composer and a well-known expert in the ashyg art Azad Kerimli argues that two of these melodies, “Bash divani” and “Shah Khatayi gerailysy” (in ashyg song repertoire the same melody can often be entitled two or more names – so are the melodies Bash divani and Shah Khatayi gerailysy – which are also known these days respectively as Shah Khatayi divanisi and Shagayi geraily) were composed by Miskin Abdal, who was the creator of the poetic form of divani (Kerimli 2000, 69).

Divani is a strophic poem, each line of which consists of 15 syllables. Most frequently divani poems deal with spiritual and philosophical subject matters. Some ashygs believe that Miskin Abdal was also the author of the ashyg song Shahsevəni.

We may assume that one of the above listed melodies, the song Heydəri, was composed in honor of Shah Ismayil, (or probably to his death), as Heydər was one of various pen names of this great shah, Sufi poet, and sheikh of safaviyya dervish brotherhood.

Nevertheless, whoever was the author of these melodies, it is obvious that the music style of such melodies as Shah Khatayi, Bash divani (Example 1), Sultani, Urfani (Example 2), Ibrahim peshrosu (Example 3), Ibrahimi (Example 4), Mansuru (Example 5), Heydəri (Example 6), and a few others, is more archaic than the style of many other classical ashyg songs. These melodies are distinguished with a short range, repetition of the melodic phrases, variable, or often free, musical meter, and frequently ended shifting the final tone from the tonic to another pitch. Modern ashygs are probably right referring them to the group of melodies they call təkkə havaları or also səmayi havaları, i.e. melodies that are meant to be performed in tekke during the sama` rites.

Dervish Mystic Practices of the 18th Century

The ties of the ashyg music with dervish rites can be traced also in the dervish mystic practices of the 18th century. Azad Kerimli (2000), quoted above, made available the interesting facts on one of the outstanding Azerbaijani ashygs of the 18th century, ashyg Allahverdi, who was more known as Ag Ashyg. Ag Ashyg literally means “white ashyg”, and his name was connected to the physical distinction of himself, namely he was an albino. It is believed that Ag Ashyg lived between 1775 and 1880. The grandfather of Ag Ashyg, sheikh Osman, was murshid of a Sufi dervish community in Nakhchivan.

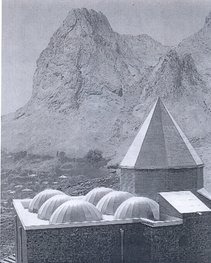

Sheikh Osman and his brother Gara Osmanoglu sang and played saz perfectly well, although they did not display their aptitude for the ashyg art anywhere but at the dervish rites held in tekke in Nakhchivan (Kerimli 2000, 69). To a certain degree, the work of the Russian ethnographer Konstantin Smirnov (1878-1938) on history and ethnography of the Nakhchivan district (see Picture 1) may support these facts.

Picture 1. Old Dervish khanegah in Nakhchivan, the region on the South of Azerbaijan on theborder with Iran.

In his work written in 1934, Smirnov mentioned the tombs of many Sufi dervishes, two villages with the name Khanegah, a village Dervishler, the Mosque Pir Khamus of the sect nuktaviyya, the Mosque Zaviye, (Zaviye was a small Sufi dervish tekke), the waterway called ‘Bektashi arkhy”, and many other traces of dervish's culture that remained in the area at the time of his research. In addition, this work also contains some useful information of dervishes in Nakhchivan from the first half of 1930s. (Smirnov 1999, 88).

Azerbaijani Ashyg Culture in the 19th and 20th Centuries

The Cult of Imam Ali

By the 19th century mystical spiritual practices, along with the title haqq aşiqi, have been gone from Azerbaijani ashyg culture, although the religious and mystical motifs remained an inspiration for ashygs even in the 20th century. These motifs were mainly associated with the name and cult of Imam Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, and the twelve imams. In Azerbaijani spiritual culture, particularly, with the Shia ummah of Azerbaijan, (where partly the population is Shia, partly Sunni), the person of Imam Ali is highly admired, sometimes as high as the Prophet himself. Some Shia sects, such as, for instance, ”ali-ilahi” go so far as deitify him. Shia has become the official religion in Azerbaijan since the reign of Shah Ismayil Savafi in Iran and Azerbaijan, exactly since the early 16th century.

However the cult of Imam Ali had found its adherents in Azerbaijan before the 16th century. Below is a fragment from a 14th-century poem, a panegyric in honor of Imam Ali:

Ta təhildən mənim könlümdə soltandır Əli,

Həm əlif, həm nüqtəyi, həm hərfi-Qurandır Əli.

Bu Nəsimi madihi-Heydər, qulami-Heydəri.

From the very beginning the sultan of my heart was Ali,

Ali is the first letter, and the final point, and the word of Koran,

I am Nasimi – meddah of Heydar, the slave of Heydar.

(Əlizadə, 1995:17. Translation by the author)

Note: Heydər, one of the epithet names of Imam Ali, an anrabic word for “lion”; it is used in a figurative sense in the meaning of “brave”.

The ancient genre of panegyric called mədh, or mədhiyyə has had a long history in Oriental poetry; it has been traditionally dedicated to the rulers – shah, khan, sultan, or khaqan. The poem quoted above is a sample of so-called Əli mədhi, the genre of panegyrics in honor of Imam Ali; its author, an outstanding Azerbaijani classical poet Imadaddin Nasimi (1369-1417), claims himself to be meddah of Imam Ali, i.e. his panegyrist. The genre of Əli mədhi, (which has remained in use in Shia religious practice and dervish rites up to now), was popular with the poets of the Shah Ismayil Khatayi` mejlis (poetic circle). Khayati himself was the author of such poems. Below are two lines from one of his panegyrics to Imam Ali:

Ey iki aləm pənahı, şahi-sərvər, ya Əli,

Sahibi-fəzli vilayət, şir-e Heydər, ya Əli.

Oh, protector of two worlds, head of shahs, oh Ali,

King of generosity, lion Heydar, oh Ali

(Əlizadə, 1977:112. Translation by the author.)

The genre of Əli mədhi was the one we find also in the poetry of ashyg Gurbani:

Indiyədək ustadımı bilmirdim,

İndi bildim, Şahi-Mərdan Əlidi.

Ümidim bağladım Şahi-Mərdana,

Əli dedim, ələyindən ələndim

I have not known till present who is my Master

Now I have realized that this was Shah-i Mardan Ali

I have placed my hopes in Shah-i Mardan,

appealed to Ali (and) have gone through his sieve [literally]

(Əlizadə, 1977:341. Translation by the author.)

The cult of Imam Ali, as well as of his sons Hussein and Hassan, Shia martyrs, has found its reflection in the poetry of a number of the great Azerbaijani ashygs of the 19th and early 20th century, such as outstanding ustads (masters) ashyg Aly (1801-1911), ashyg Alasgar (1821-1926) and Ashyg Musa (1830-1912). The greatest master ashyg Alasgar was an author of many spiritual poems, including ones glorifying Imam Ali and his sons Hussein and Hassan. Below are lines from the spiritual poems of ashyg Alasgar, ashyg Musa, and ashyg Aly.

Ashyg Alasgar (Dahilerin divani, 2013):

Həqiqətdən iki gözəl sevmişəm,

Birisi Məhəmməd, birisi Əli.

Məhşər günü darda qoymaz ümməti,

Əsğər qucağında şah Hüsеyn gəlir».

I have loved two glorious people of Truth,

One is Muhammad, the other – Ali.

On the Judgement Day shah Hussein will not leave

his ummah in troubles,

There he's coming with Əsgər in his arms.

(Translation by the author)

Note: Əsğər is the name of Imam Hussein`s youngest, six-month-old son murdered in Karbala. Professor Vasim Mamedaliyev kindly explained the author the meaning of this phrase for Shia people as “God will forgive everything to Imam Hussein just for the sake of his six-month old baby, an innocent victim.”

Ashyg Aly:

İmam Həsən gözəllərin gözüdü,

İmam Hüseyin şəfaətçi özüdü.

Imam Hassan is the heart of the Excellence

Imam Husein is the life-giving one.

_________________________________

Ashyg Musa:

İsmimdən Aşıq Musa,

Şahi-Mərdan quluyam.

My name is Ashyg Musa,

I am a Shah-Mardan`s slave.

__________________________________

(Əlizadə 1995, 18. Translation by the author)

Note: Shahi-Mardan is atraditional addressing to Imam Ali.

Conclusion

In the Soviet times religious and mystical motifs practically disappeared from the ashyg poetry, but the traditional beginning of an ashyg mejlis (literary and music party) with an opening exlamatory phrase “Ya İlahi, ya Mövlam, уa şahi-Mərdan, səndən mədəd!” («Оh, God, oh, my Master, oh, shahi-Mardan, help me!), i.e. with the addressing to God and to Imam Ali, still existing up today. Nevertheless, the art of modern Azerbaijani ashyg is thoroughly secular; it is not used in dervish rites any longer. Mystical and dervish practices in Azerbaijan have been twined around the Mugham since the 19th century, and the art of Mugham became another major genre of Azerbaijani traditional music. But this is the topic of the second part of this work.

References

- Axund, Hacı Kərbəlayı Soltan Hüseynqulu oğlu. 1997. Şah İsmayıl Xətayi. (Shah Ismayil Khatayi). Baku: Ozan.

- Baghirova, Sanubar. 2015. “The One Who Knows the Value of Words: The Ashiq of Azerbaijan.” Yearbook for Traditional Music, vol.47: 116 – 140.

- “Dahilərin Divanı” Collection. 2013. arxiv

- Əlizadə, Axund Hacı Kərbəlayı Soltan. 1995. Azərbaycan dərvişləri və rövzəxanları (Azerbaijani dervishes and rovzekhans). Baku: Boz Oguz and Nicat.

- Gölpinarlı, Abdülbaki. 1985. 100 Soruda Tasavvuf. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Gul. academia.edu

- Kərimli, Azad Ozan. 2000. “Göyçə aşıq məktəbi.” ("Göycha Ashyg School"). Musiqi dünyası, № 1(2): 66-72, part 1, Baku.

- Məhəmmədcəlil, Məhəmməd, and Fariz Xəlilli. 2003._ Mövlana İsmayıl Siracəddin Şirvani_. (Movlana Ismayil Sirajaddin Shirvani). Baku: Adiloqlu.

- Qasımlı, Məhərrəm. 2002. Şah İsmayıl Xətayinin poeziyası. (Poetry of Shah Ismayil Khatayi). Baku: Elm

- ____. 2007. Ozan-Aşıq sənəti. (Art of Ozan and Ashiq). Baku: Ugur.

- Smirnov, Konstantin. 1999. [1934.] Materialı po istorii i etnoqrafii Naxiçevanskoqo kraia. (Materials on history and ethnography of Nakhchivan district.) [Tiflis], Baku: Ozan.

- Sadıq oğlu Çingiz. 1988. "Azərbaycan təsəvvüfü tarixində 'Səfəviyyə' və onun Xətai yaradıcılığında yeri." ("Safaviyya order in the history of Tasavvuf in Azerbaijan and its role in the works of Khatayi.") In Şah İsmayıl Xətai. Məqalələr toplusu. (Shah Ismayil Khatayi. Collected articles), 58-70. Baku: Elm.

- Xətayi, Şah İsmayıl. 1988. “Keçmə namərd körpüsündən”. Şerlər və poemalar. (“Don`t cross the bridge of the treacherous one. Verses and poems.) Baku: Yazichi.

Discography

- Azerbaijan State Radio company archive. Recording of the 1960s. Heydari (also Mammadhuseini, or Kürdü). Performed by ashyg Akber Jafarov (1933-1990) and Abbasali Ismayilov on the balaban, lyrics by ashyg-poet Mammadhusein.

- Baghirova, Sanubar. 2010. CD 9, track 5. Bash divani, (also Shah Khatayi divanisi). Performed by ashyg Kamandar Efendiyev (1932-2000), lyrics by haqq ashiqi Dirili Gurbani. In Audio collection “Classical heritage of Azerbaijani ashygs.” Baku: Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Azerbaijan Republic.

- Baghirova, Sanubar. 2010. CD 1, track 18. Mansuru. Performed by ashyg Avdy Avdyiev (1910-1987), lyrics by ashyg Avdy Avdyiev. In Audio collection “Classical heritage of Azerbaijani ashygs.” Baku: Ministry of culture and tourism of Azerbaijan Republic.

- Baghirova, Sanubar. 2010. CD 12, track 14. Ibrahim peshrosu (Shirvan regional version of the song Ibrahimi). Performed by ashyg Mahmud Niftaliyev (1946-2002), lyrics by haqq ashiqi Abbas Tufarqanly. In Audio collection “Classical heritage of Azerbaijani ashygs.” Baku: Ministry of culture and tourism of Azerbaijan Republic.

- Efendiyev, Kamandar, perf. ashyg. 1982. Ibrahimi. Lyrics from the medieval ashyg love dastan “Ashiq Garib.” Azerbaijan State TV archive.

- Garayev, Ramin, perf. ashyg. 2015. Urfani (also Ruhani). Lyrics by haqq ashiqi Dirili Gurbani. Recorded by the Azerbaijan State Radio company. Used by courtesy of the performer.