#3 Analysis Of Creative Employment Of Texts In Laz Ekwueme’s Vocal Works

UDC: 78.071.1 Еквуеме Л.

781.7

COBISS.SR-ID 163935241

Received: Sept 12, 2024

Reviewed: Nov 10, 2024

Accepted: Dec 29, 2024

#3 Analysis Of Creative Employment Of Texts In Laz Ekwueme’s Vocal Works

Citation: Omotosho, Mary T. 2025. "Analysis Of Creative Employment Of Texts In Laz Ekwueme’s Vocal Works." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 10:3

Abstract

In furtherance of scholarly contributions to documentation of the works of notable Nigerian art music composers, this paper aims to bring to limelight Laz Ekwueme’s creative employment of texts in his vocal works. He was the only composer among his contemporaries without any musical influence from his parents, and with no financial comfort. Due to the composer’s proficient and dynamic application of texts in his works, the paper is set to trace the source of Ekwueme’s passion for music in connection to his creative usage of texts, and analyse his compositions accordingly. This study relies on interviews held with the composer, score reading of his music compositions, and relevant literature. The paper is anchored on the theory of creative ethnomusicology, pioneered by Akin Euba, in describing Ekwueme’s musical artistry in text-setting of his compositions. Various thematic vocal works comprising thirty (30) sacred and secular music were analysed, some of which include carols, fanfare, anthem, spirituals, folk songs, glee, mass, and introits. The analysis reveals poetic creativity, rhyme patterns, symmetrical lines/alignments, cultural permutations, lyric syllabification, re-appropriation of texts in arrangements of existing works, text-juggling, careful text-setting to music, new formation and application of existing nonsensical syllables for emphasis, humorous textual employment, and general aesthetics. In conclusion, Ekwueme’s texts, sourced as influenced by his environments, are anchored and evidenced in the creative application of information gathered from his music research. His method of textual employment will enhance the compositional skills of upcoming art music composers.

analysis, theory of creative ethnomusicology, creative employment of texts in music, african choral music

Introduction

The author has already stated (Omotosho 2020, 166) that the crucial difference between a vocal music and an instrumental composition is text. Ekwueme (2001, 18) affirms that “vocal music implies the use of words.” Through a composer’s creativity, nonsensical words are transformed into meaningful ideas of exclamation and emphasis when performed. With the engagement of musical elements in vocal and instrumental works, texts which distinguish them (vocal/instrumental) require thoughtful and creative inset to music, otherwise, vocal music would be devoid of its essence. Dictions and clarity of texts during performance thus become cogent for audience appreciation.

The observation and application of tonal languages to music are also vital for appropriate employment in vocal music compositions. Generally, texts should fittingly be assigned (set and aligned) to each music note of a composition. Text in African vocal music is largely premised on functionality for relevance and so is dependent on the context of a composition. The functions give meaning to the vocal work, resulting in meaningful interpretation to the audience. It has been observed that apart from rhythm, texts are highly esteemed to the African since they (texts) always bear a message, even in exclamations.

Laz Ekwueme

Laz Ekwueme, popularly known as a choral music composer (Omotosho 2017, 37), concerns himself with all the aforementioned when writing his vocal works. He observes that:

perhaps one of the strongest characteristics of African music, outstanding in comparison with the music of other culture areas – especially those of the western world – is its functionality (Ekwueme 2004a, 23-24).

In a bid to extend the spread of this quality, he notes that:

a composer of African choral music must be interested in reaching out “to the larger world who may benefit from the exposure to his creative input.

One of the ways he has achieved this is through his song texts.

Picture 1._ First Interview Session with Laz Ekwueme, University of Lagos Staff Quarters, 2011. Source: author.

Ekwueme’s creative musical input is sourced from early childhood experience in the village up till higher education received abroad. He was privileged to have received formal education throughout his years from age 5, despite growing up under very hard and painful conditions and losing his father at the tender age of 6 (Omotosho 2013, 43 & 2017, 37): an achievement he worked hard for and which eventually won him government scholarships at home and abroad (Omotosho 2017, 57). Although he was the only one out of his contemporaries without any musical influence from parents, he is considered as "perhaps the most learned of the most prominent group of Nigerian composers" (Omojola 1995, 67). With 11 degrees and diplomas obtained from abroad, inclusive of different language studies, his eloquence is outstanding (Omotosho 2013, 45-47 & 2017, 40-41). This study thus analyses the ways by which the composer creatively employs texts in his vocal works.

Theoretical Framework

The textual content of Ekwueme’s works reveals evidence of creative application of information gathered from his music research over the years. Hence, this paper relies on the theory of creative ethnomusicology in discussing the methods by which the composer employs texts in his musical works in relation to contexts. Euba (2001) defines creative ethnomusicology as a process whereby information obtained from music research is used in composition rather than as the basis of scholarly writing. Godwin Sadoh (2020) in his tribute to Euba, affirms him as a pioneer of the theory, among others.

In Brukman’s (2017, 142,145-146) discourse of creative ethnomusicology and African art music, he observes Caplain’s employment of the theory to be premised on close musical readings of Wood and Clay, Kundi Dreams and Umrhubhe Geeste compact disc recordings of Oboe in Africa. This paper also relies on close score readings in analysing Ekwueme’s song texts. Folami (2018, 1) asserts that “to understand Africa, especially from the viewpoint of arts and culture, it is pertinent to listen to her poets”. Referring to poets he adds that “there are those who put their own songs (poems) on paper while there are some who only speak, sing or chant theirs orally.” Ekwueme belongs to the first category, being an art music composer. His poetic nature of composing music is worthy of note and that essence this paper brings to limelight.

Scope Of The Study

Through an analytical perspective, this paper focuses on the creative formal ordering of texts in Ekwueme’s vocal works. Due to the eclectic nature of his compositions (Omotosho 2013, 157&171), the analysis covers thirty (30) selected vocal works which comprise both sacred and secular works under various themes such as politics, carol, anthem, introit, folk songs, biblical theme, mass, fanfares, glee, and so on. The works are compositionally sourced melogenically, logogenically and pathogenically, that is, melody-borne, language borne and inspiration borne, respectively. All three are rooted in his musical backgrounds.

Ekwueme’S Sources Of Texts

Laz Ekwueme is eloquent in diverse languages - local and foreign, and creatively engages words in music. His early exposure to western education from foundational years of age 5 to higher education greatly accounts for his eloquence. Despite growing up without financial comfort, his exceptional brilliance earned him government scholarships to secondary school in Nigeria and higher institutions abroad. His very humble background which was spent in the village was rich in folk musical experiences with exposure also to church songs. All of the aforementioned positively affected his skills in music compositions.

His first musical exposure which began in the village with folk music while listening to tales by the moonlight, participating in play and work songs, and ceremonies, explains why most of his songs are folk music. Religious activities in the Church laid the foundation for his sacred songs such as introits. His poetic lines in both sacred and secular songs are reflective of formal training received in western education while multilingualism through gifting and formal western studies are exhibited in his employment of diverse languages in his vocal works.

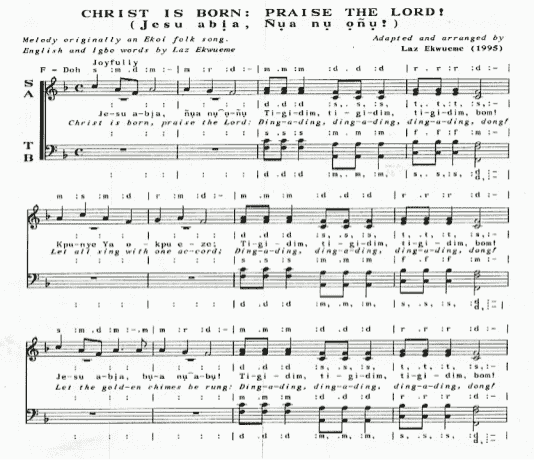

Ekwueme’s texts are premised on contextual usage and drawn from the three sources of composition to a good balance such that he is unable to specifically state his most frequently employed. He states during an interview held with him that “quite often as we hear many songs or see many things, new ideas come”. His creatively woven diction, imagery and grammar, aid his creativity in textual alignment to music. He disclosed how he adapted the texts for some of his works. For example, in a logogenic form, he adapted Kabiyesi to Kabiyesi Olorun Oba! after listening to it in a Pentecostal church in Lagos. Also from a logogenic source, he retained the original texts of Missa Africana (African Mass) but arranged the music such that it expresses africaness in the mass. One of his Christmas carol compositions - Jesu Abia, Nua Nu Onu! (Christ is Born: Praise the Lord!), was sourced melogenically using the parody technique on an Ekoi folk song. He inserted English and Igbo texts into the melody as seen in Example 1.:

Example 1. An Ekoi folk song, parodised into a Christmas Carol

Compositions done by Ekwueme for political reasons involve the text and music being sourced either pathogenically or logogenically (Omotosho 2020, 168). For instance, “Let my people go” (biblical-sourced-texts) was adapted for a ‘somewhat’ similar situation. In discussing how he gets inspired, Ekwueme described the word inspiration as “a word that could be interpreted in several ways.” He explains further that:

it means something that motivates you into some creative activity and it can be something you heard, that you enjoy so much that it moves you into trying to do something similar or against or dissimilar from it. It may even be something that you don’t like at all and you think you should do something to show how it should be done or to react to it.

Picture 2. Laz Ekwueme, sharing his compositions with the researcher - Chorale House, 2012.

The composer’s reaction to the situation affecting his place of origin was the outcome of the negro spiritual, “Let my people go”, inspired by the story of the Israelites as slaves in the land of Egypt. Moses was sent by God to tell Pharaoh, King of Egypt, to let the Israelites go. The composer arranged the vocal work at the peak of the Nigerian Biafran war in 1968 when Kwashiorkor was also at its peak. The composition was done because the Igbos wanted Biafra.

Ekwueme explains that “the antecedent to Biafra of course was the killing of the easterners of the Federal Republic of Nigeria showing vividly in unequivocal way that we were not wanted in Nigeria.” Those able to escape to the eastern part of the country did and demanded to at least be in their own place without being molested. The eastern part was blocked from exportation and importation, thereby causing famine to spread. Many lost their lives, both young and old. This treatment made the composer see his people (the Igbos) as Israelites in the land of Egypt. Although the negro spiritual was an existing work, he decided to arrange it to suite the present context. Hence, texts such as “Go on, let my people go” in the original work were adapted to “Gowon, let my people go”. Yakubu Gowon was at the time the Nigerian military leader who served as Head of State from 1966 to 1975.

Ekwueme’s texts are also sourced from existing prayers sung as hymns and which sometimes are recited as poems. An example is the popular ‘God be in my head and in my understanding’. The prayer later became known to many as a poem (Omotosho 2020,169). The texts first originated in a French text in the 15th century by an unknown author, precisely ca. 1490. Later it was found in a Book of Hours printed by Robert Pynson in London in 1514 and afterward was printed in a Sarum Primer (a book of prayers and Christian worship resources used in the Roman Catholic Church in England) in 1558. Much later, it was revived in the early 20th century and was given many tunes, the most lasting being in the form of choral arrangements made by Henry Walford Davies (1869-1941), John Rutter (1945-) and others. In 1968, Ekwueme also contributed by writing his own arrangement of the song. Although each composer strictly retained the texts, their arrangements of the harmony differ.

In addition, Ekwueme at times translates given songs (mostly folk songs) into English language and vice-versa (Omotosho 2020, 169), for a wider reach of audience. An example is Hombe (Omotosho and Abiodun, 2022), a Kenyan folk song, which he translated into English language. Another is Ore Meta (Three Friends). In Ore Meta, his English translation of the folk song is about sensual love rather than mere friendship and play as the original version states. The nature of language employed by him in Ore Meta is feminine, poetic, and Shakespearean, while still retaining the theme about the story of three friends.

Ore Meta has been expounded elsewhere (Omotosho 2019, 69-70) in a detailed tabular format, such that Ekwueme’s translation distinctly reveals a different textual interpretation of the folk song. The cultural interpretation of the song is hidden in the original texts. As a result, the cultural meaning can only be derived through metaphorical reasoning. The text reveals traces of different dialects used, although mostly that of Egba in Ogun state while the table reveals variation in Ekwueme’s translation in comparison with the literal translation of the folk song.

Furthermore, Ekwueme demonstrates flexibility by engaging the expertise of another, in a language he finds himself not competent. For instance, the hausa texts employed in Yar’uwa Maryama Yaya Jariri Yaro? (Sister Mary, How is your Little Boy?), were translated by Mrs. Angelina Angelo as stated in the music score while the English texts are his. The composer’s works written in diverse languages, employs mostly his (Igbo language), some of which include the list below. (See Ekwueme 2001, 30-32 & 38-57 for some of the scores.)

- Amara (The Grace) (1974) – Introit

- Elimeli (Festive Ball) (1980) – Glee

- Enyi Mba, Kwenu! (Igbo Solidarity Song) (2005)

- Ihe Arima (A Great and Mighty Wonder) (1993) – Nativity Song

- Jesu Abia, Nua, Nu Onu (Christ is Born, Praise the Lord) (1995)

- Nne, Bia Nyerem Aka (Mother, I Need Your Help) (1988)

- Nno (Welcome) (1962)

- Nwatakiri Jisos, Ibiala! (2010) - Christmas Carol

- Obi Dimkpa (Brotherhood of Youth) (1980) – Glee

- Oge (Time) (1994) – Solo Song

- Ote Nkwu (Sweet Palm Wine) (1992) – Glee

- Umu Uwa Golibe (Come, Children, with Singing) (1972)

- Zidata Mo Nso Gi (Send Down Thy Spirit, O Lord) (1979) – Introit

By observing the rise and fall of any language, Ekwueme is able to retain the tonal inflection of any language he composes. Even to the point of being fastidious, he insists that every part should follow the tonality of the language of song texts, subject to the musicality which of course can always be changed when absolutely necessary.

Analysis Of The Structure Of Ekwueme’S Text

Ekwuemes’s works are predominantly strophic in nature. That is, same melody, sung to different verses of a song. As a result, the texts of the music are usually symmetrical. Peculiar to folk tales, he employs the call and response even in strophic songs. In addition are verse and chorus form. With sensible or nonsensical words, he uses exclamations to portray positive or negative meanings depending on the context of the song. Every language has exclamatory words used in expression. Ekwueme thus applies them based on the language being written for. There are however exclamations that may not be attributed to any language; just spontaneous nonsensical words used in reacting to a situation and which a composer may just explore.

The composer sometimes juggles texts in the arrangement of his music, retaining or interchanging them within a voice or between voices. He also changes the texts or translation of some lines or words, just to maintain the tonality of the language and also for aesthetic purposes. Examples include but not only, Yar’uwa Maryama Yaya Jariri yaro? (Sister Mary, How is your little boy? See Song 1.) - strophic form for SATB; Umu Uwa Golibe (Come, Children, with Singing, See Song 2.) – Call and Response performed as Solo and Chorus for women choir, and Elimeli (Festive Ball): Call and Response for SATB. Just a few of Ekwueme’s compositions are through-composed. Examples are, God be in my head and Amara (The Grace). However, all are metrical in structure. Three folk songs are analysed in a tabular form below, to clearly reveal the structure of Ekwueme’s texts.

Strophic Structure In A Christmas Carol Folk Song: An A Cappella In English And Hausa Languages Respectively.

Song 1. Yar’uwa Maryama Yaya Jariri Yaro?

(Sister Mary, How is your little boy?) (2002) SATB

Verse 1.

Yar’uwa Maryama yaya wanna karamin jariri ya ro?

Yaya jin dadin hutu ko yana kuka ne?

Yaya murna, yya murna koshi sosai.

Hutu da jin inuwan a manglam gadon koshi

[Sister Mary, Sister Mary, How is your little boy?

Is He cosy, Is He cosy, or does He cry?

He is happy, He is happy and all well fed.

He is happy, cosy and snug in all His manger-bed.]

______________________

Verse 2.

Danuwa Yusuf, yaya dan jaririn yako?

Kayi mashi kayan na jin dadi?

I da madra sosai dakuma gurasa gurasa;.

Yana murna kwance a mangalam gidonsa.

[Brother Joseph, Brother Joseph, How is the little boy?

Did you make Him cheering, a cheering toy?

Yes, indeed with milk and honey to eat with his bread and honey;

Happy He sleeps, gently lying on His manger-bed.]

Call And Response Structure In A Christmas Carol Folk Song: An A Cappella In Igbo And English Languages Respectively

Song 2. Umu Uwa Golibe (Come, Children, with Singing) (1972)

Women Choir (Solo Voice and Two-Part Chorus of Soprano and Alto)

THE OPENING

Text juggling is employed in the arrangement of this song and it is done in different sections, beginning with the opening in Solo (Call) and Chorus (Response) form. The solo is taken by a soprano voice while chorus is taken by soprano and alto voices. Although this section is sung as a single verse, the structure of the texts appears in verse form of 3 stanzas merged together, without any break in-between. The same tune is sung to these ‘3 stanzas’ just as in strophic form. The author has therefore split the single verse into three stanzas for easier understanding as seen below. A closer look will reveal text juggling between the hausa and English translations. Not all lines are literally translated into hausa. See the first lines of stanzas 1 and 2. Do the same for the second line of stanzas 1 and 2 as well. Line 3 of stanza 1, reveals a different meaning in hausa when compared to the English texts. The name Mary appears in the hausa version but does not in the English version.

| No. | Igbo | English | Nonsensical Syllables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solo (Call) | Solo (Call) | Sop. & Alt. (Response) | |

| 1. | Unu uwa golibe | Come, children with singing | Samala |

| 2. | Nulianu golibe | Set the bells a ringing | Samala |

| 3. | Na Mary a mugo | Your voices a raising | Samala |

| 4. | Messiah abiago! | Jehova is praised! | Samala |

| 1. | Unu uwa golibe | Come, children with singing | Samala |

| 2. | Nulianu golibe | Set the bells a ringing | Samala |

| 3. | Jehova ekwugo! | God is man becoming | Samala |

| 4. | Na Jesu abiago | The Messiah is coming! | Samala |

| 1. | Onye amuma bialu | Hearken to the angels, | Samala |

| 2. | isachapu njo nine | Hear what tidings good the tell. | Samala |

| 3. | Onye Ngozi bialu | Mankind is so blest | Samala |

| 4. | Izoputaa yi nine | A Saviour comes on earth to dwell. | Samala |

SECTION A

The music proceeds into section A with the chorus now singing the exact same texts sung in the opening (as shown above) but with modification of melodic lines in the soprano and alto voices which now perform as call and response respectively, while solo is silent. The response however commences just before the call and onwards interlocks in the course of the music with slight extension of exclamations ‘e’ and ‘ewo’. (‘e’ is the abbreviation of ‘ewo’) as seen in Table 2.

| No. | Igbo | English | Nonsensical Syllables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soprano (Call) | Soprano (Call) | Alto (Response) | |

| 1. | Unu uwa golibe | Come, children with singing | Samala e ______ |

| 2. | Nulianu golibe | Set the bells a ringing | Samala e ______ |

| 3. | Na Mary a mugo | Your voices a raising | Samala e ______ |

| 4. | Messiah abiago! | Jehova is praised! | Samala e ______ |

| 1. | Unu uwa golibe | Come, children with singing | Samala______ |

| 2. | Nulianu golibe | Set the bells a ringing | Samala (Ewo/Yes Lord) |

| 3. | Jehova ekwugo! | God is man becoming | Samala E, Samala |

| 4. | Na Jesu abiago | The Messiah is coming! | Nwa Chineke |

| 1. | Onye amuma bialu | Hearken to the angels, | Samala |

| 2. | isachapu njo nine | Hear what tidings good the tell. | |

| All parts then simultaneously sing Samala, once, followed by the last 2 lines, in unison: | |||

| 3. | Onye Ngozi bialu | Mankind is so blest | Samala |

| 4. | Izoputaa yi nine | A Saviour comes on earth to dwell. | Samala |

You will observe above that Nwa Chineke was also used as an exclamation even though they are words and not nonsensical syllables. Nwa Chineke means Son of God. Ewo is an exclamation in Igbo language which can be used to express a positive or negative reaction. In the context of this song, it has been positively used, going by the lyrics of the song. While Ewo is sung for Igbo version, ‘Yes Lord’ is sung as an exclamation for the English version. Ewo does not mean ‘Yes Lord’. It is an exclamation used to depict ‘Yes Lord’.

SECTION B

In Section B, only the first 2 stanzas are sung. Soprano is split into 2 voices, that is soprano 1 and soprano 2, while alto remains a part. However, an exchange of ‘baton’ occurs between the soprano 2 and alto voices. Alto now leads (call), while soprano 2 follows (response) without sustaining samala. That is, Samala and not Samala___. Soprano 1 also enters simultaneously in a canonic pattern with alto, repeating same lines with alto, although entering just before alto finishes a line. The three voices are thus perceived in a manner that soprano 1, soprano 2 and alto interlocks in a very creative pattern of combined canon with call and response form. This happens only very briefly, still bearing the interlocking features as Section A. Samala is afterwards sung repeatedly without breaks by soprano 2 and alto. That is, ‘Samala, Samala’ and on and on. From line 2 of the ‘2nd stanza’, soprano 2 and alto now take the response, singing sustained Samala_____, Samala______, while soprano 1 takes the call. No exclamation whatsoever is featured throughout this section.

SECTION C

Section C is a conclusion of section B in that the ‘3rd stanza’ is sung. This section is a return to the pattern in the opening section. That is, solo takes the call, while soprano and alto respond with Samala. Finally, for a complete end, soprano and alto voices sing in unison, “Come, children, with singing, Praise the Lord!” Then comes the final word “Samala”, sung in homophonic texture, and rich harmony, with both voice parts split into two. That is, soprano 1, soprano 2, alto 1 and alto 2. Section C is thus the climax of the composition. Ekwueme creatively employed texts in both Igbo and English versions, making sure that each section is uniquely active, independently and yet uniting.

VERSE AND CHORUS IN STROPHIC STRUCTURE OF A GLEE: FOLK SONG IGBO AND ENGLISH LANGUAGES.

Elimeli (Festive Ball) (1980) – Solo and SATB (Call and Response)

Elimeli (Festive Ball) is a six-versed Igbo glee, arranged for three performance styles namely, Voice and Piano, Male Choir (TTBB), and SATB Choir. It is lively and rich in homophonic texture. The first verse-structure shown in the table below, applies to all six verses. Two lines make a verse while the chorus is three lines. For voice and piano, the song is fully taken by a voice (solo), while other arrangements have similar patterns. The table reveals the three arrangements.

| Igbo | English | Nonsensical Syllables | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verse | |||

| Solo/ TT/ Sop. (Call) | Solo/ Ten. I/ Soprano (Call) | Solo/ TTBB/ SATB (Response) | |

| Obulu n’anyi geje | Come and join the dancing ball | Bum budum budu bum bum! | |

| Obulu n’anyi geje | Come and join the dancing ball | Bum budum budu bum bum! | |

| Chorus: Solo/ TTBB / SATB | |||

| Kwado, eye, mee osiso | Dancing, prancing, Back advancing | ||

| Elimeli anyi ajusi oyi o | Join in our joyous country ball | ||

| Elimeli k’anyi n’acho! | Answering every drummer’s call | Bum budum budu bum bum! | |

RHYMES

Ekwueme is a poet who exhibits rhyme patterns, sometimes with nonsensical syllables, and other times with humorous texts. He humorously projected his thoughts during a very tense atmosphere; a prevailing unrest in the country, by adapting the texts of a negro spiritual - “Go on, let them go”, for “Gowon, let them go”. Written for SATB in 1967 and dedicated to victims of the pogrom and the Biafran war, the composer combined two single-syllable words - ‘Go on’, to sound as a two-syllable name - ‘Gowon’, yet contextually serving the same purpose. Also, rhymes are employed in but not only, Christ is born: Jesu abia, Nua nu onu (Praise the Lord) and Yar’uwa Maryama Yaya Jariri yaro? (Sister Mary, How is your little boy?). The first two lines are paired with the same rhyme while the third and fourth lines are paired with a different rhyme.

The rhymes reflect only in English song texts and usually fall at the end of each line, either on the last word or last syllable (see Figure 1. and Figure 2. above). In a narrative form, the birth of Jesus is told in the 5-versed Hausa song, with each, representing the main casts; Mary, Joseph, Baby Jesus, Shepherds, and Guardian angels, respectively. In Elimeli (Festive Ball), different rhyme sounds are employed per verse, that is:

- ball, call;

- food, brewed;

- dance, chance;

- hear, near;

- tattoo, too;

- strain, refrain.

The first line of the chorus has 3 words which rhyme (dancing, prancing, and advancing) while lines 2 and 3 are ball and call. See Table 4. Umu Uwa Golibe (Come, Children, with Singing) has the same rhyme pattern in both verse and chorus (See Table 2). A similar rhyme pattern is employed in the 4-versed carol of Nne N’Eku Nwa (O Mary, Dear Mother) however, the pattern is alternated in the third verse. That is, “He rules o’er every nation, The true great Messiah; He redeems all creation, The only Messiah!” Alternate rhyme patterns are also employed in the second half of “Beware, Brother, Beware!” (1962). That is, promises, fame, misses, and names.

The composer also combines different rhyme patterns within a song. In Obi Dimkpa (Brotherhood of Youth) the rhymes are patterned differently per verse. The first verse is paired sequentially, while the second changes pattern. That is, the first and last (4th) lines of verse 2 are rhymed while the second and third lines are paired with different rhyme sounds. Thus, 1. brood, 2. done, 3. fun, and 4. hood. That is:

Loving as nestlings of a single brood;

With a firm faith so much can be done;

A boiling pot can bring so much fun;

Stretch out a right hand of brotherhood.

NONSENSICAL SYLLABLES

Nonsensical syllables in music are words, coined-up by composers, having no meaning whatsoever but are creatively used to make interesting rhythmic sound effects. Ekwueme employs them in different expressions such as exclamation, happiness, babbles, and so on., to create special effects while adding colour and variation to the whole work. He mostly applies nonsensical syllables in his Igbo works, sometimes creating for the English version of the song.

| Song Titles | Nonsensical Syllables Used |

|---|---|

| Jesu Abia Nua Nu Onu (Christ is born, Praise the Lord) | Tigidim bom / Ding-a-ding dong |

| Elimeli (Festive Ball) | Bum budum, budu bum bum! |

| Nne, Bia Nyerem Aka (Mother, I need your help) | Tinga linga ling/ Zinga zinga zing |

| Oge (Time) | Tinkololon kom |

| Ote Nkwu (Sweet Palmwine) | Igbam chikili, chin chin chin |

| Umu Uwa Golibe (Come, Children, with Singing) | Samala |

Expansion Of Vocal Music Compositions

Laz Ekwueme skillfully blows up a few lines into a large vocal work. A profound method which he uses in actualizing this expansion, is varying repetitions, for emphasis (characteristic of African music). It is done in a creative manner and devoid of boredom. Examples are Somlandele U Jesu, a Zulu Gospel song, Chineke Bu Mmo (God is a Spirit) and, Hombe. He (Ekwueme 2004b, 246) explicates that it is uncommon for contemporary Igbo choral music composers to expand the texts of a short theme into a full anthem. He has “attempted to impress some of the professionally educated composers, the necessity to emphasize the composition of music, by taking shorter lyrics, even lyrics of one line, and making a full setting of them, thereby drawing attention to the music and not so much to the words which may have to be repeated several times.” He however notes that “the lyrics must be complete and meaningful, in spite of the brevity”, so that repetitions “will re-emphasize the profundity of the philosophy expressed in the words”, without boredom.

Humorous Songs

Humour serves as positive boosters to the state of mind in a fun way. It enhances relaxation and helps to reduce stress. Hence, creative employment of humorous texts in musical compositions give bright variation to the mood of both performer and audience as found in ‘Two Lagosians’ and ‘Animal Carol’. ‘Two Lagosians’ is highly poetic with varying rhymes such as:

- nice / vice

- way / everyday

- here / there

- before / bore

- home / come

- everywhere / fair.

Syllabification Of Lyrics

As a singer, Ekwueme gives much attention to diction by deliberately emphasizing words and making sure they are clearly pronounced. Each syllable is placed under their appropriate notes and adjusted, if necessary, even if by melismatic extension as seen in his arrangement of the second stanza of the former national anthem (1979). He extended ‘God’ to two syllables, to sound as ‘Go – od’. Hence, “O Go-d of cre-ation” rather than “O God of cre-ation”. He also adds his own texts, yet retaining the original melody. In the third and last lines of the 2nd stanza of the anthem, “Guide o-ur lea-ders right”, thus becomes “Guide [Thou] our lea-ders right”.

Symmetry

When the total number of syllabic texts in each line of a composition are uniform, the music is regarded as symmetrical. In Da Sakate (Beninoire Song), each line has 13 syllables and is perfectly revealed in Section A of the music. Thus, 13, 13, 13, 13. Nne N’Eku Nwa (O Mary, Dear Mother) 6 syllables on each. Hence, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6. Where there are slight alterations in uniformity, the majority determines. Ekwueme’s works are predominantly symmetrical.

Conclusion

Since texts are a crucial part of vocal works, a pre-consideration of its employment in setting and alignment of music becomes paramount for functionality and relevance. Laz Ekwueme’s employment of texts is context dependent and his methods are varied. They include musical composition of the entire texts of an existing vocal work; strict or modified textual adaptation of existing songs; parody; expansion of short texts to large vocal works; creative repetition of words devoid of boredom; strict logogenic sourced texts; pathogenic sourced works; biblical texts; arrangement of existing works; composition in diverse languages; translation of existing song texts to English language or from English language to other languages; and engagement of external assistance in translations where he is not competent.

In addition, Ekwueme employs both sensible and nonsensical syllables/words for exclamation. He sometimes juggles texts by exchanging them between different voices. He engages in literal translation or changes the texts in a part (even if just a word) to retain the tonal inflection of a language. At other times, he changes texts simply for aesthetic reasons. Also, the texts of a song may not be the literal meaning given. These creativities originated from the composer’s childhood background in the village singing folk songs during tales by moonlight, receiving western education as early as the age of 5, his exceptional brilliancy and tenacity, and the opportunity of receiving western education at home and abroad through government scholarships. He is deliberate in impacting the society through his lyrics and accords equal attention to both text and music such that even nonsensical syllables speak. Knowledge acquired from various research are creatively applied in his vocal works comprising a cappella and vocal and instrumental works. This paper will further enhance the compositional skills of upcoming art music composers.

References

- Brukman, J. 2017. “‘Creative Ethnomusicology’ and African Art Music: A Close Musical Reading of Wood and Clay, Kunbi Dreams and Umrhubhe Geeste by Anthony Caplan.” African Music: Journal of International Library of African Music 10(30): 142-16. journal.ru.ac.za. DOI:10.21504/amj.v10i3.2200

- Ekwueme, L .E. N. 2001. “Composing Contemporary African Choral Music: Problems and Prospects.” In African Art Music in Nigeria, 16-57. Edited by Omibiyi-Obidike. Ibadan: Stirling-Horden Publishers (Nig.) Ltd.

- _____. 2004a. ‘African Music Today: A Brief Survey’. In Essays on African and African-American Music and Culture, 23-24. Lagos: LENAUS Publishing Ltd.

- _____. 2004b. ‘African Music in Christian Liturgy: The Igbo Experiment’. In Essays on African and African American Music and Culture, 246. Lagos: LENAUS Publishing.

- Euba, A. 2001. ‘Text Setting in African Composition.” Research in African Literatures, 32(2): 119-132. Indiana University Press.

- Folami, A. 2018. Contexts, Texts and Techniques in the Selected Songs of Hubert Ogunde. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Ile-Ife: Obafemi Awolowo University.

- "God be in my head." The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology. Canterbury Press, accessed December 27, 2024, hymnology.co.uk.

- God be in my head, and in my understanding. The Church of Scotland. Edinburgh. 2020. music.churchofscotland.org.uk

- God be in my Head (the Sarum Prayer). godsongs.net

- Omojola, B. 1995. Nigerian Art Music. Ibadan: IFRA.

- Omotosho, M.T. 2013. An Evaluation of the Compositional Techniques in the Vocal Music of Laz Ekwueme. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Obafemi Awolowo University.

- _____. 2017. “Laz Ekwueme: The Journey of a Music Legend”. Nsukka Journal of Musical Arts Research (4): 36-57. University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

- _____. 2019. “A Comparative Analysis of Ore Meta (Three Friends), (A Yoruba Folk Song) as Re-Composed by Akin Euba and Laz Ekwueme.” Nigerian Music Review (17): 52-79. Ile-Ife: Department of Music, Obafemi Awolowo University.

- _____. 2020. “An Overview of Laz Ekwueme’s Exploration of Texts in His Vocal Music Compositions”. Nigerian Music Review (NMR) (18): 166-188. Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife.

- Omotosho, M.T. & Abiodun, F. 2022. “Pathos in the Structure of Laz Ekwueme’s Choral Music: Hombe.” Journal of the Association of Nigerian Musicologists (JANIM) 16(1): 158-170. doi

- Sadoh, G. 2020. “Akin Euba (1935-2020) – A Tribute.” PlainsightSOUND. plainsightsound.com