#5 Soundscape on Aparo (Partridge) and its Eco Proverbial Implications in Yoruba Worldview

UDC: 784.4(669.1)

781.7(=423)

821.423.09:398

COBISS.SR-ID 109616905

_________________

Received: Aug 28, 2022

Reviewed: Nov 20, 2022

Accepted: Dec 12, 2022

#5 Soundscape on “Àparò"(Partridge) and its Eco Proverbial Implications in Yoruba Worldview

Citation: Adekogbe, S. Olatunbosun. 2023. "Soundscape on “Àparò"(Partridge) and its Eco Proverbial Implications in Yoruba Worldview." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 8:5

Abstract

Soundscape exists through the human impression of the ecological environment. Among the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria, these impressions are expressed in proverbs that are applicable in two major ways: speech and music. These proverbs are derived from folktales and human experiences through interactions with the environment. This paper therefore, examines the soundscape of selected proverbs as used in songs that center on “Àparò” (partridge) and its eco proverbial implications in human-produced (anthrophony) sounds in Yoruba worldview. The paper focuses on the nature and characteristics of “Àparò" (partridge) as metaphorically used to describe certain human behaviors. Data were elicited through cultural trajectory and purposive selection of Yoruba proverbs on “Àparò" that have adapted to songs using the Theory of Proverb Praxis by Yankah (1989). The songs were analyzed through perspectives from ecomusicological theory. This paper posits that these songs reflect wider environmental strains in Yoruba cultural ethics with implicative emphasis on hatred, jealousy, confidence, unhygienic, pride, problem, sensitivity, and equality. It recommends that the musical portrayal and connotation of human behavior in “Àparò" (Partridge) is a reflection of the socio-social meaning, alerts, balances, capacities, deficiencies, and symbols of the good, the bad and the ugly nature of “Àparò” in the Yoruba etymology.

Yoruba worldview, soundscape, Aparo, proverbs, songs, ecomusicological theory, music, implications and environment

Introduction

Eco-proverb is an element of eco-critical review which falls under the ambit of the ecocriticism theory. The eco-critical theory endeavors to place a balance between music and the environment, including human behavioral patterns which revolve around musical works with themes on eco proverbial expressions. In this connection, the crux of this paper lies in taking a new look at indigenous/traditional means of metaphorical expressions which are found in proverbial wisdoms and practical application in Yoruba land. Yoruba people are located in the southwestern part of Nigeria and are very rich in proverbs and eco-axioms which are advanced and drawn from the rich historical archive of Yoruba oral practice. Eco proverbial practices in Yoruba land have been effectively applied to discuss and solve inscrutable riddles, an attestation to this fact could be drawn from a Yoruba proverbs that “Òwe l’ẹshin ọ̀rọ̀, tí ọ̀rọ̀ bá sọnù, òwe la fi ńwa” (Proverbs are the riddles to solve a riddle). Writing on the importance of proverbs as part of the elements of cultural transmission, Akporobaro (2006), posits that “proverbs have been and remain a most powerful and effective instrument for transmission of culture, social morality, manners and ideas of a people from one generation to another”.

Proverbs uncovers the idea, insight, and verbal strategies of the past experiences and also stand as a model of a powerful medium to convey feelings and other human relevancies of life. It is on this premise that this paper examines the soundscapes of selected songs (proverbs) that center on “Àparò” and its eco proverbial implications in Yoruba etymology with focus on the nature and characteristics of “Àparò" as metaphorically used to describe certain human behaviors. The songs were analyzed utilizing perspectives from ecomusicological theory with data elicited through cultural trajectory and purposive selection of popular Yoruba songs on “Àparò”. Since proverbs are wealthy in significance, these could be utilized to express virtues in human characters, they are therefore not out of content for ecomusicological researches especially as related to nature and environmental studies which this paper intends to explore within musical portrayal and connotation of human behavior in “Àparò" as a reflection of the socio-social meaning: alerts, balances, capacities, deficiencies, and symbols of the good, the bad and the ugly nature of “Àparò” in the Yoruba etymology.

Relevance to Ecomusicology as a Field of Study

The field of ecomusicology engages the physical environment through the culture of music and sound. Although, diverse researches have been carried out on the connections of birds and musical creations, for example, Titon (2020) accounts for birdsong, its socio-cultural and environmental implications among the Yoruba people of Nigeria where he examines natural elements as socio-cultural signifiers in a selected song by Christopher Omotoso. Other scholars, such as Titon (ibid.), express how music/ecology are used as metaphors to create a natural ecological paradigm. Aaron (2012) also conceives the field of ecomusicology as a gap bridging between the sciences, arts and humanities. In Aaron (2013) ecomusicology is an area of inquiry that “considers musical and sonic issues, both textual and performative, related to ecology and the natural environment.”

Defining the relevance of this paper in ecomusicological studies, it is therefore considered as a channel to examine the relationship of birds and humans with the environment, the interactions of the three elements in the advancement of an ideal ecological relationship that is fathomed though musical creativity for correctional and appraisal purposes in the Yoruba etymology. Coiling from Allen (2014) who defines ecomusicology as, “the study of music, culture, and nature in all the complexities of those terms.” This posits that ecomusicology thinks about music and sonic issues that are analyzed in text and performance as connected with ecology and the human environment. Therefore, ecomusicology as a study of music and nature attempts to bridge the challenges of music and ecology autonomy and presents a connection to advance and strengthen the power of music and the value of environment within a particular cultural ambience.

Shirley (Shirley at al. 2018) see ecomusicology study as “a connection between humans and nature which the subject of numerous areas of research and a collective attempt to answer question of what truly makes us human as well as define how human society will conserve and coexist with nature in the future.” Titon (2009) views ecomusicology as a research area for sustainability. In his paper “Music and Sustainability: An Ecological Viewpoint”, he posits that:

ecomusicology teaches adaptational advantage of diversity. In the competition for resources, the more diverse the organisms, populations, and communities, the greater the chances of survival in, and of, the ecosystem. Thus the argument in favor of diversity is not merely grounded injustice as fairness, but also in adaptation for survival”. (p.120 )

Buttressing Titon’s position, Brewer (1994) opines that “the community and its surrounding habitat comprise an interacting unit or ecosystem.” From the positions of the above two scholars, it is evident that the study of ecomusicology emphasizes the human relationship with the environment and seeks to understand how this interrelationship has promoted the human and animal living environment.

The Theoretical Framework

The theoretical approach was advanced by Yankah (1989). The theory investigates adages in light of relevant points of view. Investigating the idea of the perception and elucidation that talking about the maxims and distinguishing its significance without response to setting, prompts overview of the usefulness of the axiom as a significant piece of the talk (Yankah 1989). Yankah states that:

The context of the proverb is crucial in navigating their content. Moreover, proverbs, due to their dynamic nature, have the potential for varied meanings. Context, therefore, helps to identify the intended meaning in a given situation. It should be noted that context in this sense includes not only the social environment in which proverbs are used, but also the social credentials of speakers and audience, and the more immediate situation of use. (p.71).

Yankah's principal contention is that the axiom is not customary discourse, it is an articulation with profound social data. Subsequently, the setting gives the system a significant comprehension of maxims.

Yoruba Eco Proverbs and Values

The selected eco proverbs for this paper are coined from the numerous proverbs in Yoruba land. These proverbs are applied to various situations as accessed by their value-based conditions. The practical use of proverbs is intertwined; a particular proverb could be used to explain another proverb. This fact goes with the position of Adégojù (2008) who posits that “proverbs are used by the Yorùbá people not only as proverbs only but also as a riddle to solve a riddle”. This is the position of a Yorùbá proverb that “òwe l’ẹsin ọ̀rọ̀, ọ̀rọ̀ l’ẹsin òwe, bí ọ̀rọ̀ bá sọ nù, òwe ni a fi ńwa’, meaning “a proverb is a riddle to solve a riddle”.

Apart from the fact that proverbs are very powerful channels of oral (speech and song) expression, they are greatly relevant and beneficial to maintain checks and balances in the society. The beauty of proverbs lies in the fact that a proverb leads to another proverb to simultaneously address any issue or issues to avoid cumbersomeness of meaning and interpretations. This may fairly explain Fasiku’s view that “proverbs have great value in generating human consciousness.” (Fasiku 2006). Fásíkù further posits that “proverbs do not introduce themselves to us as universal truths, as generalizations that always apply. Their pitch, their point, their punch is situational or context-dependent to an essential degree”. By and large, proverbs advance with the development and improvement of the general public, it reflects different parts of a group's way of life, beliefs, customs, social and political establishments, morals, economy, and wellbeing.

Nature and Characteristics of “Àparò” in Yoruba Worldview

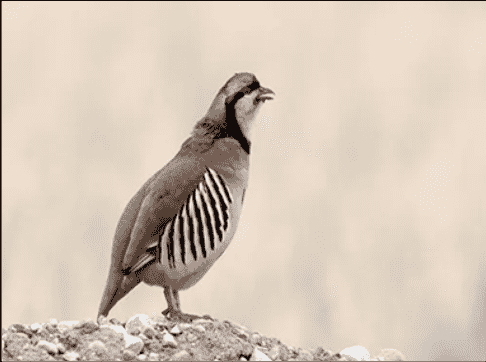

Àparò (partridge) has dark neck and chest feathers and a corroded red head. Its wing and tail feathers are brown, rust, white and dim. It has short, round wings and a little bill. There are diverse parameters in Yoruba worldview of the nature and characteristics of “Àparò” which are applied to various situational expressions in the eco proverbial parlance. “Àparò” are species of bird among others like Ayékòótọ́, Òwìwí, Àwòdì, Igún, Òrófó, Àdàbà, etc. Among the Yorùbá, there are many taboos and myths about Àparò, representing metaphorical relationships between the bird and humans which reflect meaning, alerts, and symbolism. In the Yoruba parlance, the nature of the color of Àparò connotes a lot of interpretations which are often used to describe human situations and characteristics. These applicable uses would be discussed in line with the selected eco proverbs in the later part of this paper. Figure 1 is the picture of Àparò. Due to the nature of the Yoruba ethical concept, Àparò do not make good house pets. They are wild birds, and are normally quite flighty and fearful of humans. As gamebirds, in most places it is illegal to own one as a pet among Yoruba people of the southwestern Nigeria.

Figure 1. Àparò (Partridge)

Source: Photos courtesy of Shutterstock:

Michael Hulet (Accessed

July 11, 2022).

Trajectory and Development of Eco Proverbs in Yoruba Land

The history and development of eco proverbs among the Yoruba people could be said to have advanced from folktales, actions of and reactions to observations and human experiences throughout the ages past and the present. Yoruba people often create proverbs based on animal characters, nature and habitat which has led to the development of several eco proverbs, and which have been used to metaphorically explain riddles in human existence. Complementing this position, Taylor (2003), opines that “Proverbs are the simple truths of life that contain the ethical, moral values of a society.“

The simple truths, according to Taylor, may not be logically established, but these are accepted as part of the existing norms in Yoruba land. One may need to examine the position of Yusuf (1997) that the truth presented in the proverbs is not logical, a priori or intuitive truth: it is often an empirical fact based upon and derived from the people’s experience of life, human relationship and interaction with the world of nature. In his interrogation, Nicolaisen (1994) examines the role and essence of proverbs and the connection by positing that proverbs are based on the belief of being “traditionally used as prismatic verbal expression of the essence of folk culture.”

Also, Egblewogbe (1980) sees proverbs as related to short, traditional statements used to further some social ends. From the aforementioned, proverbs have become part of the Yoruba norms that are drawn from humans and animals to further explain seemingly bleak situations for the purpose of, according to Wallnork (1969), regulating social activities, an instrument of action, conveyance of order and information, influencing people, enabling self-expression, and embodying and enabling thought. For example, several eco proverbs on Àparò are conceived in accordance with the nature and characteristics of the bird, which are often applied to human situations and behaviors. Over the years, musicians have also keyed into the use of eco proverbs to reflect the socio-social content, meaning alerts, balances, capacities, deficiencies, and symbols as part of the music industry’s contribution to the body of ecomusicological studies.

Figure 2. Àparò standing on flat earth.

Source: carolinabirds.org

Eco proverb 1: Àparò kan kò ga jù kan lọ l’áyé, à f’èyí tó bá g’orí ebè [No partridge is taller than another except for those standing on earth mounds.]

Eco Musical Application: This proverb underlies three positive concepts of equity of disposition, egalitarianism and balance, and three negative concepts of prejudice, partiality and condemnation as noticeable in the characters of Àparò. These are likened to certain characters as embedded in humans, that is God has created all humans in the same likeness except those that have decided to see themselves as being more important than others within the same category of people. Kirby (2018) posits that “ all human beings are one another’s equals and basic equality, therefore, is something to be recognized and respected.” Arneson (2013) also considers this notion of equality that “the agreement forges the unity of contemporary political thought and it is ‘the shared egalitarian plateau’ from whence all other arguments begin.” Other arguments which may come under the reason why Àparò has decided to stand on the earth mounds and what it stands to achieve in this process, which of course might be for the purpose of oppression.

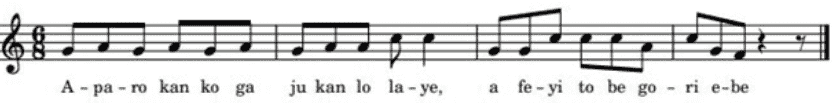

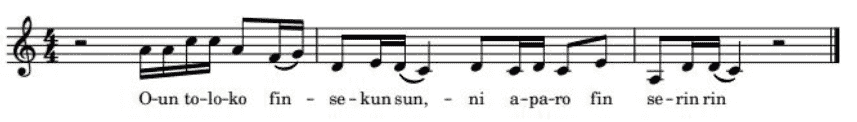

This proverb was eco-musically applied by King Sunny Ade in his music where he sings as thus "Àparò kan kò ga jù kan lọ l’áyé, à f’èyí tó bá g’orí ebè" :

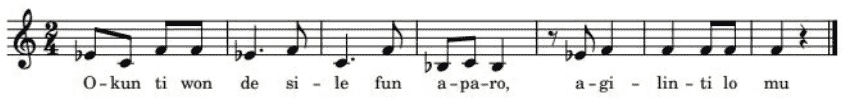

Example 1. Àparò kan kò ga jù kan lọ l’áyé, à f’èyí tó bá g’orí ebè by King Sunny Ade

Eco proverb 2: Ìgbà tí a bá p’erí àparò ní ńjáko. [Just as the talk turns to the partridge it shows up to raid the farm.]

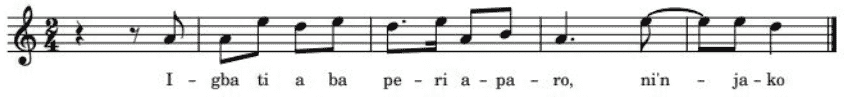

Eco Musical Application: This eco proverb is applicable when a person is considered timing, apt, punctual and very appropriate in all actions and reactions. It is applied as an appraisal of an individual who is also considered brave in the Yoruba parlance. In common parlance, personality refers to the impression, which an individual forms on others through his personal attributes making an attractive or unattractive view. This proverb was eco-musically applied by Yusuf Olatunji (Example 2) in his music where he sings as thus “Ìgbà tí a bá p’erí àparò ní ńjáko”.

Example 2. Ìgbà tí a bá p’erí àparò ní ńjáko” by Yusuf Olatunji

Eco proverb 3: Ènìyàn bí Àparò l’ọmọ aráyé ńfẹ́. [People prefer others to appear inferior and less fortunate to them.]

Eco Musical Application: The eco proverb is often applied to depict how the human is premised on the wish of misfortunes for fellow humans, it also expresses the human selfish nature for the sole purpose of oppression, especially when others are not well financially, socially or politically placed in the society. Feeling of schadenfreude (pleasure at others’ misfortune) has been well researched into by Heider (1958), Smith (2013) and Smith (Smith et al. 2009). Although schadenfreude carries a negative connotation, such an emotional reaction is widespread in interpersonal relationships.

This eco proverb on Àparò was recorded in a musical piece by Túnjí Oyèlàna (see Example 3) where he expresses the human behavior to wish others to be poor and dirty in likeness of the Partridge color brown (see Figure 3).

Example 2. Ìgbà tí a bá p’erí àparò ní ńjáko” by Yusuf Olatunji

Figure 3. Partridge.

Source: carolinabirds.org

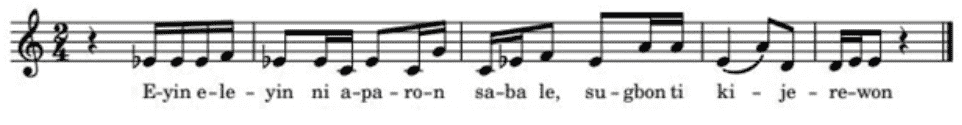

Eco proverb 4: Eyin ẹlẹ́yin ni Àparò ń'sàba lé, sùgbón tí kìí jèrè won. [The Partridge incubates and hatches eggs it did not lay, but not beneficial to itself.]

Eco Musical Application: This eco proverb is applied to define the human nature of wickedness, covetousness, unethical accumulation of common wealth, lustfulness, corruption and wastefulness. Àparò shares these characteristics with humans in terms of wickedness, covetousness and wastefulness where people grab wealth through dubious means that are presumably not necessarily useful to them. Fjelde (2009) argues that “human attitude of conversion of public funds into private payoffs could be linked to corruption.” Also, Lambsdorff (Lambsdorff et al. 2005) put clearly that systemic corruption has become a normal occurrence in human attitudes because it has been supported by human structures and conform to their social system. This is likened to the character of Àparò which has cultivated the habit of accumulating and incubating other birds’ eggs with no clear justification for doing so.

In Jerimiah 19: 11, also complements the Yoruba eco proverb that “like a partridge that hatches an egg it did not lay are those who gain riches by unjust means. When their lives are half gone, their riches will desert them, and in the end they will prove to be fools.” This eco proverb was composed and recorded by Ayinla Omowura (see Example 4) where this expression was metaphorically applied to signal warning to the Nigerian politicians who have cultivated the habit of public money embezzlement:

Eco Proverb 5: Okùn tí wọ́n dẹ sílẹ fún Àparò, Agílíntí lo mú. [A trap set for the Àparò (Partridge) will surely catch Agílíntí (Lizard family)]

Eco Musical Application: This eco proverb is often applied to a situation of danger escape. for example, if someone escapes a trap of accident and instead of the person being caught in that scene but someone else falls into the trap. This is to mean that Àparò is a sensitive bird that is so difficult to be trapped. The proverb confirms another eco proverb on Àparò that "tojú tìyẹ́ l'àparò fi nriran" (“Aparo sees with both eyes and feathers”). This eco proverb is a warning to humans to be more sensitive to situations around them. Yusuf Olatunji "Okùn tí wọ́n dẹ̣ sílẹ̣̀ fún Àparò, agílíńtí lo mú":

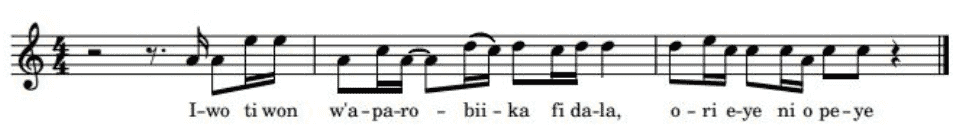

Eco Proverb 6: Iwo ti won n wo àparò bii ki won fi dálá, ori ẹyẹ ni ò pẹyẹ. [We look at Àparò as a good delicacy but its destiny forbids it.]

Eco Musical Application: Based on the Yoruba cultural belief, Àparò is a crafty species of birds that is very difficult for the hunter to catch for human delicacy. The proverb is applied to sound a warning to people that venture into fruitless actions in the society. Exploring this aspect of human behavior through functionalist theory, the position of Agoben (2018) about human behavior emphasizes that human behavior or action is a function of the social structure which is largely determined by values, norms or rules that are guiding such a society. This portends that it is naturally human to be engaged in fruitless actions or activities:

Example 6. Iwo ti won n wo àparò bii ki won fi dálá

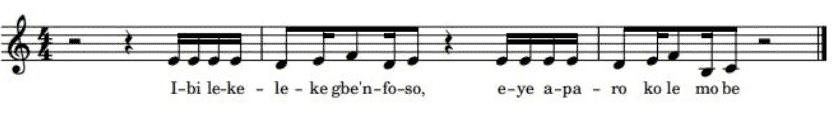

Eco Proverb 7: Ibi tí lèkeleké ti gbé ńfosọ, ẹiyẹ àparò kò lè mọ bẹ̀. [Where the Cattle Egret washes its cloth is a secret for the Partridge.]

Eco Musical Application: This eco proverb is applicable to a successful status of people in which the enemies try to know the source but could not. The proverb is likened to white nature representation of the cattle egret (white color symbolizes purity, strength, balance, concentration, longevity, freedom and independence), while the brown nature (color) of the partridge symbolizes penury. These are two contrasting elements of cleanliness and dirtiness.

Writing on cleanliness and dirtiness as social and psychological issues Speltini and Passini (2014) opine that:

the issue of cleanliness in its clean/dirty and pure/impure antinomies has a cultural tradition studied in the fields of anthropology and history. This is a theme that has, in fact, an undeniable social and cultural dimension. Even what we define as ‘‘clean’’ or ‘‘dirty’’ has varied over the centuries and within the same culture as a function of socio-cultural and religious memberships. (p.210)

The Yoruba eco proverb has placed a distinction between the two birds (Egret and Partridge) as clean as white and dirty as brown. (“Egrets are herons, generally long-legged wading birds, that have white or buff plumage, developing fine plumes during the breeding season.” Wikipedia.) This is often used to describe success and failure in comparative analysis. King Sunny Ade expresses this proverbial notion in his song Ibi lèkeleké gbé ńfosọ, ẹiyẹ àparò kò lè mọ bẹ̀, to drive home his point on his successful musical career.

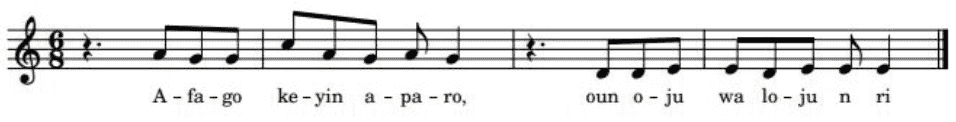

Eco Proverb 8: Af’àgò k’ẹ́yin Àparò, oun ojú ńwá, l’ojú ńrí. [Stealing of the Partridge eggs leads to misfortune.]

Eco Musical Application: This eco proverb is used to warn people to be conscious of their actions that are considered delicate and unethical in the society. Corroborating this eco proverbial position, Bewaji (2016) categorically states that:

Yorùbá value system is by far more advanced in being more eco-respecting, eco-friendly, and geared toward sustainable human habitation in a world in which he/she constitutes one small fraction of sentience which establishes relationship between values and the environment. (p.150)

Àyìnlá Omowúrà Anígilájé expresses this eco proverbial notion in his song Af’àgò k’ẹ́yin Àparò, oun ojú ńwá, l’ojú ńrí:

Eco Proverb 9: Ohun tí olóko fi ń sekún sun ni àparò fi ń sẹ̀rín rín. [One man's success amounts to others' failure or misfortune.]

Eco Musical Application: This eco proverb is used to describe the diverse nature of life about joy and sorrow. Yoruba people believe that where one has been successful might be an avenue for others to fail, it is also conceived within the Yoruba ethical understanding that human life is a blend of opposing contraries. It is a blend of such contradicting elements as joy and distress, delight and torment and happiness and stress. Dáúdà Epo Àkàrà expresses this eco proverbial notion in his song that Ohun tí olóko fi ń sekún sun ni àparò fi ń sẹ̀rín rín:

Eco Proverb 10: Eni gbé òkú Àparò, gbé áápọn. [He that carries a dead Partridge, carries misfortunes.]

Eco Musical Application: This eco proverb is used to describe situations of flogging a dead horse or venturing into a fruitless venture. The use of animal metaphor in this eco proverb is purposely to establish a discouragement of engaging in fruitless desires. Olateju (2005) corroborates this that:

From a psychological point of view, the usage and understanding of an animal metaphor involves some perception of attitudes, experiences or dispositions of both the speaker and the addressee. Unlike ordinary metaphors which people find relatively easier to understand. (p.362)

Adéolú Akínsànyà expresses this eco proverbial notion in his song that Eni gbé òkú Àparò, gbé áápọn:

Conclusion

This paper has examined the soundscape of selected eco proverbs as used in songs that center on “Àparò” (partridge) and its eco proverbial implications in human-produced (anthrophony) sounds in Yoruba worldview. It posits that eco proverbs are derived from folktales and human experiences through interactions with the environment as reflected in the nature and characteristics of “Àparò" (partridge) as metaphorically used to describe certain human behaviors. This paper posits that these songs reflect wider environmental strains in Yoruba cultural ethics with implicative emphasis on hatred, jealousy, confidence, unhygienic, pride, problem, sensitivity, and equality. It recommends that the musical portrayal and connotation of human behavior in “Àparò" (Partridge) is a reflection of the socio-social meaning, alerts, balances, capacities, deficiencies, and symbols of the good, the bad and the ugly nature of Àparò in the Yoruba etymology.

References

- Aaron, S. A. 2012. “Ecomusicology: Bridging the Sciences, Arts, and Humanities.” In Environmental Leadership: A Reference Handbook, edited by. Deborah Rigling Gallagher, 373-381. Sage Publications.

- __2013. Ecomusicology. Grove dictionary of American music. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Aaron, S. A. and D. Kevin 2014. “Current Directions.” In Ecomusicology Music, Culture, Nature. Edited by Allen S. Aaron and Kevin Dawe, 1-323. Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017.

- Adégojù, A. 2008. “Empowering African Languages: Rethinking the Strategies.” The Journal of Pan African Studies Vol. 3(3):14-32

- Agoben, T. 2018. “Unearthing the Reasons Behind the Human Behaviour in Society: A Reappraisal of the Theories in Sociological Behaviourism.” Arts and Social Sciences Journal 09.

- Akporobaro, F. 2006. Introduction to African Oral Literature. 3rd ed. Lagos: Princeton.

- Arneson, R. 2013. “Egalitarianism.” In The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Edited by N. Edward. Summer Edition. Zalta.

- Bewaji, J. A. I. 2016. “Heritage, Cultural Preservation and Management.” In Encyclopedia of the Yoruba. Falola, Toyin and Akintunde Akinyemi (eds.), 148-149.

- Bewaji, J. A. I. 2016. “Heritage, Cultural Preservation and Management.” In Encyclopedia of the Yoruba. Falola, Toyin and Akintunde Akinyemi (eds.), 148-149.

- Brewer, R. 1994. The Science of Ecology, 2nd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Saunders College Publishing.

- Egblewogbe, Eustace Yawo. 1980. “The Structure and Functions of Proverbs in African Societies.” Social Education (October): 516-518.

- Fásíkù. G. 2006. "Yoruba Proverbs, Names and National Consciousness."_ Journal of Pan African Studies 1 (4): 60-63._

- Fjelde, H. 2009. “Buying peace? Oil wealth, corruption and civil war 1985-99.” Journal of Peace Research 46(2): 199–218.

- Heider, F. 1958. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Kirby, N. 2018. “Two Concepts of Basic Equality.” Res Publica 24: 297–318.

- Lambsdorff, J., M. Taube, and M. Schramm. 2005. ”Corrupt contracting: Exploring the analytical capacity of new institutional economics and new economic sociology.” In The New Institutional Economics of Corruption, edited by J. Lambsdorff, M. Taube, & M. Schramm, 246. Routledge.

- Nicolaisen, W.F.H. 1994. “The Proverbial Scot.” Proverbium ii: 197-206.

- Olateju, A. 2005. “The Yorùbá Animal Metaphors: Analysis and Interpretation. Nordic”. Journal of African Studies 14 (3): 368–383.

- Shirley, Ethan A, Alexander Carney, Christine B. D. Hannaford. 2019. “Using music to teach ecology and conservation: a pedagogical case study from the Brazilian Pantanal.” In The 33rd World Conference on Music Education, 2018. Baku, Azerbaijan.

- Smith, R. H. 2013. The joy of pain: Schadenfreude and the darkside of human nature. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, R. H., C. A. Powell, D. J. Y. Combs, D. R. Schurtz. 2009. “Exploring the when and why of schadenfreude.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 3(4): 530–546.

- Speltini G, S. Passini 2014. “Cleanliness/dirtiness, purity/impurity as social and psychological Issues.” Culture & Psychology 20(2): 203-219.

- Taylor, A. 2003. “The Proverb, Proverbs and their Lessons.” In Supplement Series of Proverbium, edited by Wolfang Meider, 13. Vermont: University of Vermont.

- Jeremiah. 1982. The Holy Bible. New King James Version. 1982 Thomas Nelson, now HarperCollins.

- Titon, J.T. 2009. “Music and Sustainability: An Ecological Viewpoint.” In The World of Music Vol. 51, (1): 119-137. VWB - Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung.

- Titon, J.T. 2020. “Within Ethnomusicology, Where Is Ecomusicology? Music, Sound, and Environment.” Etnomüzikoloji Dergisi Ethnomusicology Journal 3(2): 194-204.

- Wallnock, J. 1969. Language and Linguistics. London: Heinemann. pp. 184

- Yankah, K. 1989. “The Proverb in the Context of Akan Rhetoric: A Theory of Proverb Praxis.” In Sprichwörterforschung, 313. Bern: P. Lang.

- Yusuf, Y.K. 1997. “Yoruba Proverbial Insight into Female Sexuality and Genital Mutilation.” ELA: Journal of African Studies, Critical Sphere (1&2): 118-127.