#9 Smiljana Mandukic (1908-1992) Beginning of Modern Dance and Dance Expressionism in Europe

UDC: 793.3

22.071.2929 Мандукић С.

793.322(497.11)"19"

COBISS.SR-ID 258620172

Received: Oct 14, 2017

Reviewed: Nov 5, 2017

Accepted: Dec 8, 2017

#9 Smiljana Mandukic (1908-1992) Beginning of Modern Dance and Dance Expressionism in Europe

Citation: Obradovic, Vera. 2018. "Smiljana Mandukic (1908-1992): Beginning of Modern Dance and Dance Expressionism in Europe." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance 3:9

Acknowledgement: I am immensly grateful to the most renowned ballet critic and publicist Milica Zajcev who gave me the complete archival material of Smiljana Mandukic. Also, my thanks and gratitude goes to the choreographer Dubravka Maletic, the former student of Smiljana Mandukic, who gave me her own files at disposal during my research; to Tatjana (Šehić) Christelbauer for her translations from the German language; and to my mentor dr. Svenka Savic.

Abstract

Smiljana Mandukić (1908-1992) a dancer, choreographer, and teacher, was among those dancers who pioneering the modern dance in Serbia. The beginning of the 20th century brought new forms of art as the old ones were not sufficient to express new feelings and experiences, in that era of rapid technological progress. Mandukic was educated as a dancer in interwar Vienna, so she happened to be at the centre of Central European expressionist dance, free dance, at the time of her formation as a dancer. Smiljana acquired dance knowledge from her teachers, famous dancers and choreographers, Gertrud Bodenwieser, who developed her own style of modern expressionist dance, known as “Bodenwieser Viennise Style”, and Grete Wiesenthal, who was a member of the corps de ballet of the Hofoper in Vienna (Vienna Court Opera Ballet). Both her teachers were the representatives of “Ausdrukstanz” or “Neur Tanz”, and were rejected formalism and virtuosity of classical dance in favour of more natural movements. Like her pair, Maga Magazinovic (1882-1968), who introduced expressionist dance in Serbia, established the first school of modern dance in 1910, and founded the first modern dance group consisted of female dancers, Mandukic advocated for the importance of dance in education of female population. In the traditional, patriarchal Serbian society, she opened the second school of modern dance in 1931, and was the first artist who established a professional group of modern dance. Her greatest achievement was the creation of “epic-patriotic choreodrama”. The main goal of this article is to confirm that Smiljana Mandukic’s pioneer work in establishing modern dance in Serbia was the part of the European expressionist modern dance movement of the equal importance and significance not only when considering the Western Balkans but the broader European context.

Smiljana Mandukic, modern dance, Ausdruckstanz, expressionism, choreo-drama

Introduction

In the beginning of the 20th century Smiljana Mandukic weaved a provocative thought of free dance movement in her homeland and its cultural-artistic courses, at the time when the modern dance was being developed and taking its significant place in Europe. Due to the fact that she grew up in Vienna and that she was a Vienna student, she was formed under the strong influence of the artists who were either her teachers or influenced on establishing and developing of the unique Vienna modern dance scene, such as Grete Wiesenthal (1885-1970), Gertrud Bodenwieser (1890-1959), Elinor Tordis, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865-1950), Rudolf Laban (1879-1958) Isadora Dunkan (1877-1927), Max Reinhardt (1873-1943), and Hugo fon Hofmanstal (1874-1929). Pioneer artistic practice of Smiljana Mandukic was definitely under the strong influence of the above-mentioned prominent Europeans from the field of modern dance and theatre.

Mandukic’s Education and Development of Modern Dance Style

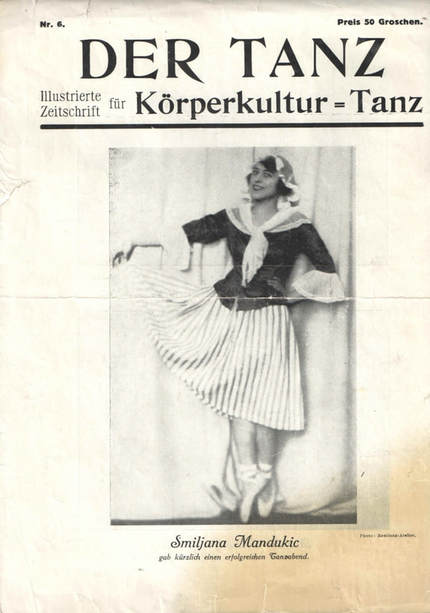

Figure 1. Smiljana Mandukić.

Smiljana Mandukic (Figure 1) was educated as a dancer in interwar Vienna, so she happened to be at the centre of Central European expressionist dance, free dance, at the time of her formation as a dancer. Smiljana acquired dance knowledge from her teachers, famous dancers and choreographers, Gertrud Bodenwieser, who developed her own style of modern expressionist dance, known as “Bodenwieser Viennise Style”, and Grete Wiesenthal, who was a member of the corps de ballet of the Hofoper in Vienna (Vienna Court Opera Ballet). Both her teachers were the representatives of “Ausdrukstanz” or “Neur Tanz”, and were developed under the influences of Isidora Duncan, Rudolf von Laban, Mary Wigman, and Ruth St. Denis, who rejected formalism and virtuosity of classical dance in favour of more natural movements.

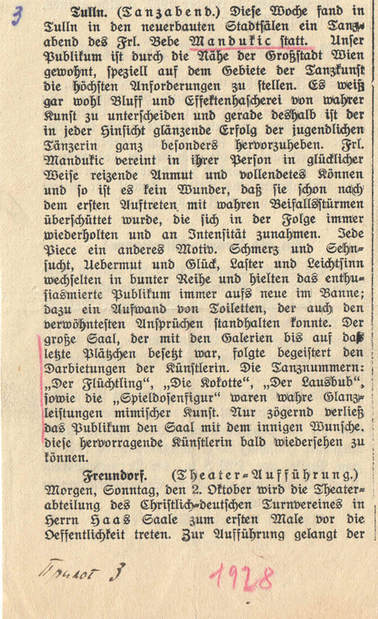

Figure 2. Cover page of the magazine Der Tanz, 1928. (Archival material provided courtesy of Milica Zajcev)

Since being educated in German language and cultural environment, Smiljana Mandukic adopted alternative direction of expressionist dance, Ausdruckstanz, as a new view of art which she brought to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and Serbian region. She acted under the influence of Viennese school of dance and choreography by rejecting what was felt as artificial to the body in classical dance, tamed by strict discipline, technique and figure.

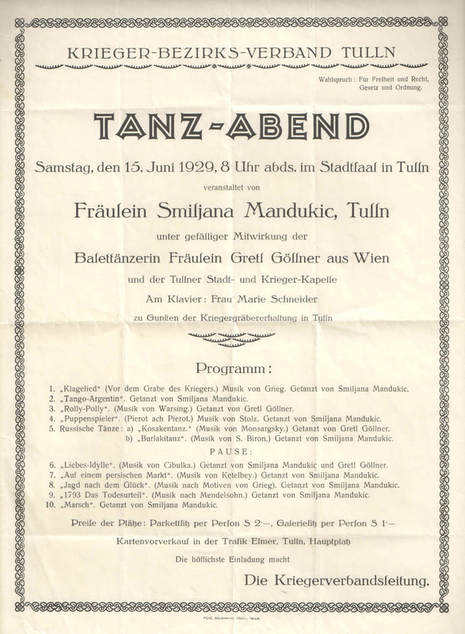

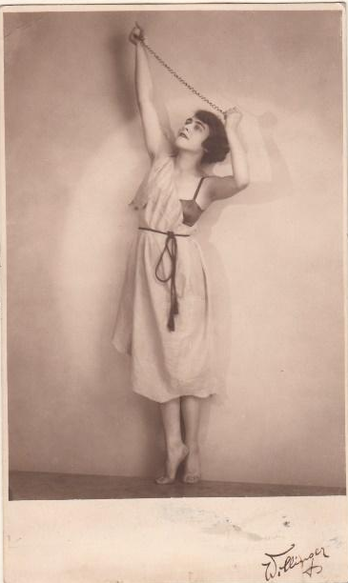

Smiljana Mandukic’s performances were very successful in her home-town of Vienna, as well as in Tulln and Graz, according to „ Der Tanz“ magazine, which put her on its 1928 cover page (Figure 2). After her solo performances in Tulln (Figure 3, and Figure 4), she returned to Serbia with exceptionally positive critiques (Figure3). After she came back to Serbia, she continued her pioneer work and put in a lot of efforts to establish modern dance.

Figure 3. Critique after Smiljana Mandukic’s performance in Tulln. Original page from an unknown source found in Milica Zajcev’s archival materials.

(Translation from German: Tulln. (Dance evening) This week Miss. Beba Mandukic held her dancing performance in the newopen Assembly Hall in Tulln. As Tulln is not far from the cultural center of Vienna, our audience is familiar to the highest quality of performances, and particularly in the case of dance art is capable to recognize differences between triviality and strutting, artificial body and the real, genuine dancing art. Therefore, the brilliant success of the young and talented dancer is worth emphasizing. Fortunately, Miss. Mandukic embodied in her uniqueness exciting chastity and perfected knowledge, and therefore it is not strange that she has got long, standing ovations after very first of her performance. In each part of her performance different motifs appeared, from pain, longing, suffering, and grief to arrogance, and recklessness, and each was enthusiastically applauded by the audience who, too, were enthusiastic about her subtle, sumptuous embroidered costumes. The audience in a grand hall, which was full until the last seat in a gallery, were watching the breathtaking performance of the artist in the following brilliant choreographic scenes: “Refugee,” “Flirt,” “Rascal,”and “The figure from the music box.” The audience reluctantly left the hall, expressing their wish to see this extraordinary artist again, and hoping it will be soon. (Translated into Serbian by Tatjana Šehić Christelbauer)

Figure 4. Poster/program for Mandukic’s choreographic dancing performance held in Tull, Jun 15, 1929. (Archival material provided courtesy of Milica Zajcev)

The establishment and development of modern dance and dance drama (choreodrama) in Serbia

We can neither state that the crisis of classical ballet dance in Serbian theatre in the early 20th century led to the phenomenon of modern dance, nor that there was a deliberate separation from the classical technique, poetics and aesthetics. Classical ballet as a form of theatre art did not exist on the Serbian scene at the time. The School of Classical Dance was opened in Belgrade National Theatre in 1921 (Kosik 2017; Jovanović, 1994, 20), eleven years after the first school of modern dance was established by Maga Magazinovic in 1910 (Mosusova 1993). Smiljana Mandukic joined Maga Magazinovic’s efforts to bring modern dance to the Balkans. She opened the second Belgrade school of modern dance in 1931. Consequently, we can state that Maga Magazinovic and Smiljana Mandukic were the founders of an expressionistic modern dance movement in Serbia in the beginning of the 20th century, which was the new dance style at the time in the patriarchal environment in which they came. They transferred this new dance style, born and developed at the time in Europe and America, on the Serbian dance stage. They were both unorthodox artists, brave at connecting traditional and avant-garde, national and European, even though they received ambivalent reactions form their environment regarding their work. Modern art of dance stemmed from their schools.

In addition, contemporary national dance drama, which the author defined as “epic-patriotic choreodrama”, was developed in the pioneer works of these two artists (Obradovic Ljubinkovic, 2016a, 2016b). The very titles of their choreographies contained the allusions on dramatic contents based on myths from epic tradition. However, neither Mandukic, nor Magazinovic, conceived their choreographic works as choreodramas. (Choreodrama can be defined as the deep synthesis of dance, pantomime, music and acting.) Their pioneering works on the establishing of that theatrical genre in Serbia can be regarded as intuitively operated by both artists. Their preferred artistic forms were choreographic miniatures, so their theatrical performances were often in the form of the divertimento. Both were dedicated to national themes, rooted deeply in the collective subconsciousness and memories of the Serbian people. Additionally, Smiljana Mandukic found her inspiration in the music of national composers. Her main tendency was towards the creation of modern national dance in accordance with the national spirit, and set to the music of national composers who were her contemporaries, but established on the more relaxed, freestyle form of modern expressive dance movements.

In her review, ballet critique and publicist Ms. Milica Zajcev referred to Mandukic’s choreographic work “Concentration Camp” as choreodrama (Zajcev-Darić 1976). It was on the occasion of hosting “Belgrade Contemporary Ballet of Smiljana Mandukic ” dancing troupe at the Ljubljana Dancing Days Festival, in 1976. “Concentration Camp” was dedicated to the Yugoslav peoples’ battle against fascism. The troupe consisted of female dancers: Ksenija Sekačić, Divna Petrović, Jadranka Mujanović, Nela Radovanović, Ljubica Šerbula, Dušica Milanović, Olga Marković. “Concentration Camp” got the festival award. Given that there is no video recording of the performance of the above-mentioned choreodrama it is not possible to analyze the structure of the choreography. Unfortunately, there are numerous performances of Mandukic which are not recorded and archived, so that it is not possible to determine and differentiate her abstract dances from her dance dramas that melded dance and drama, i. e. choreodramas.

Dubravka Maletic, in her paper "A sketch for the portrait of the dance enthusiast – Smiljana Mandukic" published in the magazine Teatron, 78, 79, 80 (Maletic n. y.), gave an overview of choreographic works of Smiljana Mandukic. A number of titles of the Mandukic's opus listed in Maletic's paper has been chosen by Vera Obradovic, and which Obradovic referred to as choreodramas (Obradovic Ljubinkovic 2016a). The chosen works are: "Slave" (on the music of Sergei Rachmaninoff), "The Death of Jugovic' Mother" (music by Stanojlo Rajcic), "Trilogy of a Woman: Girlhood, Motherhood, and the Last Battle" (compilation), "The Death of Jugovics' Mother" (music by Rajko Maksimovic), "Peer Gynt" (music by Edvard Grieg), "Barefoot Dancer" (music compilation), "Concentration Camp" and "Skull Tower" (both on the music by Dusan Radic).

Figure 5. Smiljana Mandukic in her choreography "Slave."

In choreodrama “Slave”, Mandukic described suffering of enslavement, the feeling of joy and sweetness of freedom after the slave’s flight, and then his death, marked the beginning and the end of her choreographic opus. The first performance of the “Slave” was gave in Belgrade, Serbia, in 1928, when Mandukic performed solo dance with Lovro von Matacic (1899 - 1985) at the piano; later on, with her dancing troupe “Belgrade Contemporary Ballet of Smiljana Mandukic ” she made new version of her choreodrama which was performed for the last time in Belgrade again, in 1991. Mandukic pointed out subsequently detected coincidence that the music by S. Rachmaninoff (Prelude in C sharp minor Op. 3 No. 2) inspired both Isidora Duncan and herself to make the choreography with the same motif, considering that the theme of slavery was forced by the music score (Zajcev 1992). After the 1928 performance of the “Slave,” when she was dancing herself and when new free modern dance style was introduced and presented to the Belgrade National Theatre audience, Serbian critiques, although familiar with the modern dance from earlier performances of Maga Magazinovic, could not determine if Mandukic performing was an acting or dancing. Given that Mandukic began her dancing education in a classical ballet tradition (with Cecilia Ceri, prima ballerina at the Vienna Opera House), felt by Mandukic as restraining and shackled by tradition and from which she released herself for the sake of freestyle modern dance movement, the choreography of her “Slave” (Figure 5) can be considered to be her autobiographical note.

Another choreodrama which the author took for analyzing, choreodrama Trilogy of woman, was performed at the Kolarac Great Hall in Belgrade in 1943, as a part of a whole night’s performance under the title “Modern Dance of Smiljana Mandukic.” The structure of this choreodrama was built from fragments, the form she kept in her later works. The following parts were the constituents of the trilogy: Girlhood, Motherhood, and the Last Battle, thus demonstrated the life cycle of a woman, namely the crucial moments of her lifetime. In that eternal circle youth, marriage, old age and death forever alternate. This choreography was featured by Danica Mokranjac, Sonja Radovanović, Dubravka Kabalin, Gela Jovanović, Radica Karaklajić i Radmila Zafirović. They acted prayers, children and mothers. In the Girlhood the choreographer used golden apples as a symbol of the young girls’ beauty that passed quickly. The one who was courageous enough to leave the golden apple went further on in her life, with the bride veil given to her and put on her head by her girlfriends. Then she passed through Motherhood, described with pray, children’s play and the joyful round. In the Last Battle, the time came for the experience to gather, for the past to be remembered, and talked over, but the dance developed sad features, while the steps of the dancers towards the out-world shore were becoming more heavier and gloomier. Given that the trilogy began with the girlhood we can explain the choreographer main ideas: on the one hand, it was the concept of maturation, defined as the predetermined unfolding of genetic information, development which occurs in fixed stages that are governed by genes, until the moment when the girl became conscious of her gender, and on the other hand it was the apotheosis of a woman, or the allegory of the resurrection and the salvation of life after the war.

The fragmentary structure characterized another choreodrama, The Barefoot Dancer, performed in 1969 at the People’s University of Veselin Maslesa in Belgrade, which was dedicated to the life and work of Isidora Duncan. The Barefoot Dancer was split into ten scenes, i. e. choreographies: First Meeting with Music, Spring, Kiss, Journey to Greece, My School, Journey to Russia in 1905, My Children are Dead, America, Moscow in 1921, and Good-buy my Friends. In the choreodrama Mandukic used music compilation from Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Ottorino Respighy, Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Joaquin Rodrigo and others. She was inspired by Isidora Duncan’s autobiography under the title My life. The narration was played by Danica Mokranjac, who was her pupil and actress. In the choreodrama she exploited various motifs, one of them being love between Isidora Duncan and Sergei Yesenin (Сергéй Алексáндрович Есéнин, 1895-1925). With her free style dance she proposed new concept of woman’s freedom which meant woman’s emancipation, and was comparable with Isidora Duncan’s efforts in the same matter.

Mandukic's choreodramas were based on the script. The above-mentioned choreodramas were integrated into a choreographic entirety with narration. Inspired by the Serbian epic poetry, Mandukic made several versions of Jugovic mother’s death choreography. The first version was danced on Stanojlo Rajcic’s music, and the second version on the music by Rajko Maksimovic. Moreover, Maga Maazinovic, another modern choreographer, dancer and pedagogue in Belgrade, had this title in her opus, too. This was the way by which both women expressed their patriotic feelings, by which they influenced Serbian society, and fight for the new concept of woman’s freedom. Both artists exploited themes and motifs from national epic poems, which having been historical past, events or memories recorded or orally transferred, formed into the collective consciousness identity of Serbian people. They were searching for dance which could be the harmonious unity of both national and European characteristics, traditionalism and modernism. Both, Smiljana Mandukic and Maga Magazinovic advocated for the establishment of national dance, on the basis on the national folklore as well as on the stylization of free modern dance. Their pioneering creation was dance drama defined by the author as epic-patriotic choreodrama because of its national and patriotic features (Obradovic Ljubinkovic 2016a, 2016b).

Theoretical works of Smiljana Mandukic

Smiljana Mandukic wrote several theoretical works. Unfortunately, not many of them were published. Her most significant was 'Body Language' (1990), a book originally written as the textbook for anyone interested in learning about modern dance. Another was an article published in the magazine Our stage 90-91 (1954) under the title “About Modern and Classical Dance”. In the program of the Matinée held at the National Theater in Vracar, Belgrade, on December 17, 1939, her accompanying text was published, under tha title “A few words on rhythmical dances”. In addition, her unpublished papers with reflections on her lifetime, her dance, and comparisons between classical and modern dance and its essence were numerous.

In her very concise text “A few words on rhythmical dances,” she wrote about differences between classical ballet and modern dance:

Rhythmical dances, called by many as modern dance or modern ballet, are in fact the oldest dances which we’ve ever had. Rhythmical dance springs from the rhythm, and the rhythm is as old as the life itself (...) It is very dangerous to make comparison between ballet and rhythmical dances, because the pioneers of that so-called modern ballet are very much under the influence of classical ballet. Between these two styles the core difference is that ballet develops its course according to the prescribed form and the music with its theme determined by the composer, whereas rhythmical dance generates naturally and has free flow. (Mandukic 1939)

Like Isidora Duncan, Mandukic preferred modern dance conceiving it as the art of the future. In her later, broader article “About classical and modern dance” Mandukic wrote:

Modern dance is the expression of the soul, feeling, and emotion, of human being. In other words, it is based on the natural human instincts and urges for the movement, whereas classical ballet is made of the artificially-prescribed set of movements which, undoubtedly, could be very interesting, picturesque, very virtuosic and technically precisely produced, and accordingly very appealing, but they do not spring out of the essence of music, but are imposed upon the dancers to work them out in the given moment. (...) Moreover, classical ballet already belongs to history itself. It is so much the symbol of one past period of dance development that it cannot be the means for reviving the spirit of other times. (Mandukic 1954, 3)

Body Language

Mandukic wrote her book “Body Language” (1990) before the end of her life, when she had not have as much strength and vitality as she used to have in her previous, the most productive period, when she had written her article “About Classical and Modern Dance” (1954). We must point out the fact considering her unique use of the term “Body Language” - she used it as the title of the textbook, as the title of her whole night’s choreographic performance, and as the title of her two documentary television films with the theme dealing with her artistic and pedagogical work. Her first documentary “Body Language” was shoot in 1986, for TV Belgrade, under director Srboljub Bozinovic, and the second was from 1991, for the same TV Belgrade, but the author and spiritus movens of the latter was Anita Panic (director Suncica Jergovic). Unfortunately, the latter was not saved in the TV Belgrade archive.

Given that the term “Body Language” is repeated continuously , we can construct semiotics and discourse model that suggests the conclusion that for Mandukic the dancing body has meant the language, the movements being letters, representing together the means of communication, the “writing”, the source of symbolic meanings. “Movements can be read as writing. They have their symbolic meanings” (Mandukic 1990, 6). She argued that this “writing” was understandable to all nations on the planet. Verbal expression through one’s native language was not the only way of communication, but there was also non-verbal type of communication, through body movement, body writing. She talked about choreography as it was a sort of a painting, painted by dancing movements which simultaneously appeared and disappeared in the space. That means that creativity is an ongoing process of continual change and reaction.

We could argue that it was the same idea as the one of the contemporary theorist and linguist Roland Gérard Barthes (1915–1980), who reflected over the origin of the writing (variations in writing), and wrote:

For the father Jakob van Ginken the first human language was that of gestures. That gestural language would yet be conventional language (which could be found in ideograms, in the graphic transcription of whatever was, although outside the words, a code: a social guest). Later, much later than it was suggested, the articulated language would be created.(Barthes 2010, 42)

According to Barthes the writing could be described as „manual gesture“ contrary to oral, vocal gesture, and that translated into the dance language could be referred to as the following: dance would be a body gesture, a form of personal writing of the body in the space, and the result of that writing would be a choreography, which would communicate the meanings of the executed movements. The second semantic feature of the writing could be partly applied to dance, namely that the writing meant a set of signs that won the victory over Time – dance was victorious over Time at the moment of dancing, as the sum of virtual, current signs that „simultaneously appeared and disappeared in the space“ according to Mandukic. The third Barthes‘ semantic feature of the writing that defined it as:

the endless practice in which the whole being is engaged, contrary to the simple transcription of the messages. Thus the writing enters into the opposition even with the speech (...) Or better, it is according to its use and philosophy, a guest, a rule, and pleasure. (Ibid.)

It could be transferred onto semantic of dance, as the codified practice engaging the whole being – his body, soul and spirit. Mandukic trained dancers in her troupe through the exercises which she made herself in order to enable them to “write”, and to “speak” her choreographies.

Coreographic intertwinings:

Bodenwieser–Wiesenthal-Mandukic

Smiljana Mandukic as a student at the Vienna Art Academy adopted her knowledge from famous and eminent artists: Gertrud Bodenwieser (1890-1959) and Grete Wiesenthal (1885-1970), who were leading personalities of the Vienna Ausdruckstanz movement. Moreover, their dance was closely connected to drama, dramatic expression, and theatre performances, which we can spoke of to be multimedia at the time. They nurtured a unique style, technique and philosophy of dance. Gertrud Bodenwieser perceived classical ballet as an ordinary exhibition of virtuosity, and she questioned this by her intention to realize essential powers of human sensibility. Therefore, she accepted the influence of François Delsart (François Alexandre Nicolas Chéri Delsarte, 1811-1871), Isidora Duncan, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze and Rudolf Laban (Cuckson and Reitterer 1993) She did not reject classical technique completely, but employed it as necessary warming up technique, which she rejected in her choreography creation. Bodenwieser closely cooperated with Max Reinhardt (Gertrud Bodenwieser 1890-1959 by Marina Sassenberg).

The uniqueness of style Gertrude Bodenwieser was recognizable for in the fields of expressionist dance was called “Bodenwieser Viennise Style“. She used improvisation and spontaneous dance, which on the one hand had to be either an adequate response to music or completely independent from it, and on the other hand had to be understandable, explicit language. The meaning of movements had to be clear. For her as well as for other modernists, improvisation was the search for personal dance vocabulary, and movements were initiated from the emotional part of personality and breathing rhythm. Accordingly, Smiljana Mandukic adopted such relation towards the dance during her studying at Vienna State Music Academy with Bodenwieser who taught two subjects, Pantomime and Dance. Her teacher also included Dalkroze’s method of Eurhythmics in the curriculum.

In addition, Bodenwieser established a dance group with which she toured around Europe, America and Japan, and was considered to be the leading person of Ausdruckstanz (Warren and Warren 2013). However, Nazism made her share the destiny of her contemporaries and she was expelled and became a part of dance ex-pats. Unfortunately, most documents regarding her Vienna period were lost or destroyed due to the war. Consequently, the artistic work of Gertrud Bodenwieser remained insufficiently recognized and explored. Her leaving the European continent contributed the founding and development of modern dance on another continent, Australia. She took with her most of her dance group „Tanzgruppe Bodenwieser“. She became a pioneer of modern dance in Australia, founding the first ballet company in Sydney called „Bodenwieser Ballet“.

Having a comparative insight into one of the most frequently staged Bodenwieser’s choreographies, Dämon maschine or Demon Machine, which was awarded in Italy in the beginning of the 20th century, and Mandukic’s choreographic work Robots, we can see a clear and obvious influence of Bodenwieser on the aesthetics and work of her student. The works are unavoidably comparable, but we can talk of interactive inspiring influence of the student, Smiljana Mandukic, and her teacher, Bodenwieser. We can provide the proof by Bodenwieser’s choreography „Yugoslav Dance“.

Video 1. Dance of the Steppes by Gertrud Bodenwieser

G. Bodenwieser’s and S. Mandukic’s choreographic contemplations on human existence, society and the world, their thoughts about machine dehumanizing man and his life, the possible consequences of inventions which took human souls by making humans man-machine, were very similar and had an obvious close connection. Moreover, they both contemplated this topic in the beginning of the 20th century. Assuming that Vaslav Nijinsky’s „ The Rite of Spring“ was a visionary prediction of social turbulence and the First World War, Kurt Jooss’s „The Green Table“ predicted the Second World War, then choreographic obsessions of portrayal of man-machine in the works of Mandukic and Bodenwieser predicted modern way of living in the hi-tech world. Both artists offered social, psychological and political topics in their creative work and dance dramas, by searching for human values through explicit dance expression. Mandukic created scene images and movements in the way related to the choreographic language of G. Bodenwieser. She drew movements from dancers, she intuitively crystallized their kine-spheres, and in the outcome she shaped and composed them according to her own ideas and thoughts.

Smiljana Mandukic brought Vienna expressionist dance practice to the national dance scene, she brought modern legacy of Wiesenthal/Bodenwieser which marked a necessity to devote attention to the rhythm and the sense of rhythm and spontaneity. She used to say that each person held their own individual inner rhythm which they should follow. Everyone should work on their own being and uniqueness of the body through dance, from which they should create different modes of movement. Generally speaking, that was the imperative of Austruckstanz in Europe: the genuine dance.

The second artistic and pedagogical role model for Smiljana Mandukic was Grete Wiesenthal, who strove to explore a method for relating music and movement. It seemed to her that acrobatic classical movements did not have the real connection with music, and that the classical dance tapped into formality, conventionalism and lifelessness by not allowing emotions and thoughts to find their expression through movement. However, she did not feel that the classical ballet should be rejected. In fact, her appearance in modern dance was more interesting due to the fact that she was initially taught on classical ballet and adopted the basis of classical technique. She was different from the most of the other modernists: she wasn’t autodidact. She experimented with Chopin and Strauss’s waltzes and with Dionysus component and cheerfulness that he found in them. She tried to explore dramatic form through her dance. Working closely with H. Hofmanstal she connected pantomime with dance. She drew her inspiration for movement and motion from nature.

Smiljana Mandukic adopted the same approach as Grete Wiesenthal, considering the classical ballet more of a social event than an artistic act. Also, she considered dance as the means of exploring and creating through unornamented movement and without artificial body posture, through symbols. Both dancers grounded their theoretical work by writing essays on the art of dance and gesture. Both of them built their special system and movement technique.

There were testimonies regarding Wiesenthal’s work, which stated that she could make her soul visible through simple movement and gesture, and that her dance and gesture language seemed cleansed from any excess, intuitive and touching. Smiljana Mandukic accomplished the same with her dancers. Expressiveness of Wiesenthal’s arms and her dance, which was totally different from classical code which she felt unbearable and accoringly liberated herself from its chains, changing even the popular waltz, fascinated and spurred Mary Wigman (1886-1973), by tracing her path towards the art of dance.

The expressiveness of Grete’s hands while performing The Blue Danube Waltz particularly impressed Mary. Her memoirs recount: ‘The Blue Danube Waltz deeply impressed me... For the first time in my life I saw that hands can be more than hands, that hands can become buds and flowers that can bloom before one’s eyes... (Manning 2006, 51)

Grete Wiesenthal, who was succeeded by Mandukic, brought significant innovations to the dance technique by avoiding static classical poses and by searching for the fluid dance movement. Wiesenthal was led by an idea to avoid routine of daily classical exercises that might drown creative potential. Smiljana Mandukic, who gained the knowledge of Wiesenthal’s innovations in technique, equally tried to establish her own inventive exercise system, i.e. modern dance exercise.

In building the movement, she started from five positions, adding wave, swaying and freedom of upper body and feet. At everyday warm up, the movement did not stop when changing positions, it was continual and connected. Therefore, we can state that the pattern was almost the same. In fact, both Bodenwieser and Wiesenthal questioned dance movement in a continuous incessant flow as a waving movement and swaying, which also existed in Mandukic’s exercise system. Accordingly, we can conclude that Maga Magazinovic and Smiljan Mandukic, who were the first advocates of modern dance in Serbia, started from the same point as their predecessors and teachers who established and developed the expressionist dance movement in Europe. They found original natural generic movements which belonged to the bodies of dancers they worked with as well as to their life experience.

In addition, it must be pointed out that there were another strong influences by Max Reinhardt and Hugo fon Hofmanstal, who alongside dance pantomime revived interest in non-verbal dance drama theater, as well. Their fruitful mutual and creative connection and cooperation with Ausdruckstanz dancers, Gertrud Bodenwieser and Grete Wiesenthal and the expressionist dance practice, left a deep trace in Serbia and Serbian choreodrama tradition. Smiljana Mandukic directly reflected and inherited teachings and influences of German art of choreodrama, European expressionist dance movement, and due to that the existence of choreodrama in the Western Balkans was accepted and has been developed to this day.

On the other hand, talking about both Serbian and former Yugoslav space, the importance of Smiljana Mandukic on the development of modern dance is obvious, which is also true when considering much broader European space. Accordingly, her contribution to that pioneering work on the creation and development of modern dance in Europe must be remembered. Her work and influence in the socio-cultural context of the former Yugoslavia and Serbia particularly should be an area of concern and the topic of the further research.

Award „Smiljana Mandukic“

The UBUS (The Serbian Ballet Dancers Association) Award „Smiljana Mandukic“ for the best dance interpretation in the field of contemporary dance was founded twenty years after she died, and is awarded onece every year. The following dancers have been awarded until 2017: Nikola Tomašević (2012 and 2016); Strahinja Lacković (2012); Bitef dance company for the performance Yesterday – Remember to forget (2013), Ana Ignjatović Zagorac (2014), Rikardo Kampuš Freire (2015) and Dejan Kolarov (2017).

Conclusion

The artistic path of Smiljana Mandulic was much more the path of the choreographer and dance pedagogue than that of the dancer. She brought the avant-garde thinking and inovations in the field of modern choreography. Accordingly, it should be considered the possibility to be awarded another prize annually for the best choreography or dance drama (choreodrama).

Note

The part of this paper was the part of the PhD thesis defended at the University of Novi Sad, Department of Gender Studies, and was published in the author’s book Choreodrama in Serbia in the 20th and 21th Century: Gender Perspective.

References

- Barthes, Rolan. 2010. Задовољство у тексту & Варијације у писму. (The Pleasure of the Text &Variations of the Writing.) Beograd: Službeni glasnik.

- Bodenwieser, Gertrud. Bodenwieser’s choreography "Yugoslav Dance". youtube

- Cuckson, Marie and H. Reitterer. 1993. Bodenwieser Gertrud (1890-1959). adb.anu.edu.au

- Jovanovic, Milica. 1994. Првих седамдесет година. Балет Народног позоришта. (First Seventy Years. National Theatre Ballet.) Beograd: Narodno pozorište.

- Kosik, Viktor. 2017. "Russian Ballet Dancers and Choreographers at the Belgrade Stage in the XX and Early XXI Centuries." Accelerando: Belgrade Journal of Music and Dance (2): 8

- Magazinović, Maga. 2000. Moj život. (My Life.) Beograd: Clio

- Maletic, Dubravka. 1993. "Skica za portret plesnog entuzijaste – Smiljana Mandukic." ("A Sketch for the Portret of one Dance Enthusiast – Smiljana Mandukic.") Teatron 78.79.80. (February): 187-194. Beograd: Muzej pozorišne umetnosti Srbije.

- Mandukić, Smiljana. 1939. "Nekoliko reči o ritmičkoj igri." ("A few words on rhythmical dances.") In the Program of the performance held at the National Theatre in Vracar on December 17, 1939. Belgrade: National Theatre.

- ____. 1954. "O klasičnom baletu i modernoj igri" ("About Classical and Modern Dance.") Naša scena 90-91 (1954): n. p. Novi Sad.

- ____. 1990. Govor tela. (Body Language.) Beograd: Sfairos.

- Manning, Susan. 2006. Ecstasy and the Demon. The dances of Mary Wigman. Minneapolis-London: University of Minnesota Press

- Mosusova, Nadežda. 2012. "Moderna igra u Srbiji. Povodom stogodišnjice rođenja Mage Magazinovic i stogodišnjice njene škole." U Zborniku XIV Pedagoškog Foruma Scenskih Umetnosti: Igraj, Igraj, Igraj. ("Modern Dance in Serbia. On the Occasion of the Centenary of the Birth of Maga Magazinovic‘s School.") In A Collection of Procedings of the XIV Pedagogical Forum on Performing Arts: Dance, Dance, Dance, edited by Milena Petrovic. Beograd: Fakultet muzičke umetnosti u Beogradu.

- MS 9263. Papers of Gertrud Bodenwieser (1890-1959). nla.gov.au

- Obradovic, Vera. 2003. "Smiljana Mandukic – ličnost Srpkinje iz Beča." U Zborniku Matice Srpske za scenske umetnosti 28-29, urednik Božidar Kovaček. Novi Sad: Matica Srpska ("Smiljana Mandukic - A Serbian woman from Vienna." In The Collection of Matica Srpska for Perfoming Arts 28-29. Edited by Božidar Kovaček.)

- Obradović Ljubinković, Vera. 2016a. "Koreodrama u Srbiji u 20. i 21. veku: rodna perspektiva." Doktorska disertacija. Univerzitet u Novom Sadu, ACIMSI, Centar za rodne studije, Novi Sad. ("Choreodrama in Serbia in the 20th and 21th Century: Gender Perspective." PhD thesis defended at the University of Novi Sad, Department of Gender Studies. )

- ____. 2016b. Koreodrama u Srbiji u 20. i 21. veku: rodna perspektiva. (Choreodrama in Serbia in the 20th and 21th Century: Gender Perspective.) Novi Sad: Zavod za ravnopravnost polova.

- Sassenberg, Marina. Gertrud Bodenwieser 1890-1959. jwa

- Warren Vernon, Bettina and Warren, Charles. 2013. Gertrud Bodenwieser and Vienna’s contribution to Ausdruckstanz. (Choregraphy and Dance Studies Series.) Hoboken, NY: Taylor and Francis

- Zajcev-Daric, Milica. 1976. "Одраз домета и могућности." ("Reflection of Range and Possibilities.") Borba January, 17.

- Zajcev, Milica. 1992. "Prva dama moderne igre". ("First Lady of Modern Dance") Scena (4-5): 123-125. Novi Sad: Sterijino pozorje.